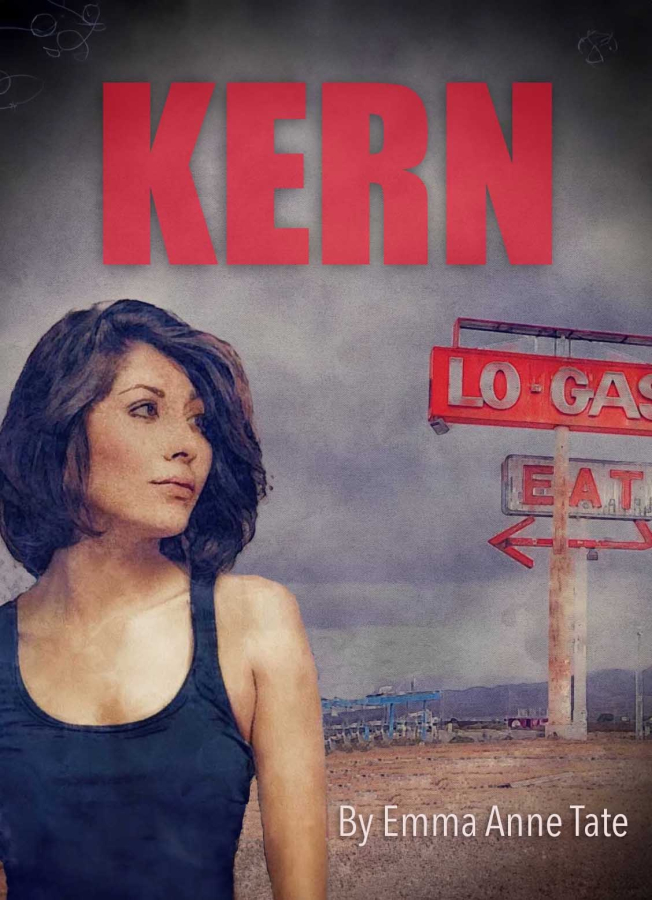

Kern - 38 - Of History and Eternity

Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

Permission:

Carmen Morales works for an insurance broker in Orange County, attends law school at night, and shares an apartment with two other women, Lourdes and Katie. On the surface, everything is normal – a typical American story in the 2020’s.

But Carmen was christened Carlos Angel Morales at birth – the eldest child of the youngest son of a large, Kern County Chicano family. Her mother disappeared when Carlos was eight and her brother Joaquim (“Ximo”) was five, leaving them with their father, Juan, and taking only their two-year-old youngest brother, Domingo. Just before Carlos turns 18, Juan discovers she is trans and kicks her out.

Eleven years later, Juan has a massive stroke and falls into a coma. Her grandmother (“Abuela”) tracks Carmen down and calls her back, ultimately getting her to agree to be Juan’s conservator on a temporary basis. While Carmen goes about the task, she also reconnects with family and learns more than she ever knew about her parents.

As July gives way to August, Carmen returns to Kern for the sixth time, intending to end her term as conservator and pass the duties to Ximo. While visiting Juan in the hospital, she is surprised by her mother, who has come to make peace with him. Carmen and her mother don’t make it out of the hospital before they run into Abuela, Carmen’s Aunt Juana, and her cousin Alejandro (“AJ”).

For a refresher on Carmen’s family tree, see this post.

Chapter 38: Of History and Eternity

Momma winced, then struggled to get to her feet. Tia Juana and Jill Thomas, the duty nurse, moved to help her. But Abuela’s question, softly stated, seemed to linger in the air, like the smell of ozone after a lightning strike. Why are you here, Kathy?

Acting purely on instinct, without pausing long enough for any second thoughts to catch up to me, I said, “No, Abuela. This is not happening.”

She turned her face toward the sound of my voice with all the crazy accuracy I had come to expect, and her eyebrows lowered dangerously over dark and sightless eyes.

But I kept going, my voice less sharp than firm. “She came on her own; no-one asked her. She’s leaving now, but she’s going to come talk with me and Ximo first. That’s it. We’re not going to have a family inquest in the middle of the ICU.”

Jill muttered something that sounded suspiciously like, “got that right!”

Abuela, on the other hand, glowered at me, speechless. The silence between us felt tense. Heavy. Freighted with meaning.

Then, to my complete surprise, she chuckled. “Fine. We’ll do it your way. Your mother told me she wouldn’t return; as far as I’m concerned, she hasn’t. Nuera?”

Tia Juana shot my mother a startled look, then said, “I’m here.”

“We’re here to see Juan. Let’s see Juan.”

But my aunt looked at her son instead. “Could you take her, AJ? I’ll be down later.”

“Sure,” he said. He took Abuela’s upper arm.

She looked bemused at tia Juana’s decision, but she said nothing more. As soon as she felt AJ’s steading hand, she started marching in the direction of padre’s room.

Everyone got out of her way.

Once they’d gone, tia Juana said, “Kath? Can I come for a bit, too? There are a couple things I’d really like to tell you, before you go.”

Momma still looked a bit woozy, but she nodded. “Okay.”

I sent Ximo a text. Headed to the cafe on the first floor

His reply came just as the elevator showed up. K. Just parked

Jill told my mother to go somewhere she could sit for a bit, drink some water and have a bite to eat. Then we got into the elevator and made our way downstairs.

As soon as the door closed, Momma said, “I never saw anyone talk to suegra like that.”

Tia Juana smiled. “Kind of a treat, wasn’t it?”

Momma giggled. “Kinda.”

I wasn’t sure what to say to any of that. I hadn’t set out to defy Abuela, and I couldn’t even say why I’d felt the urge to defend Momma. My own feelings about her were as coherent as a toddler's first scribbles. So instead of responding, I ushered them across the atrium to the hospital’s cafe and herded them to the booth furthest from the doors. “Momma? What can I get for you?”

She shook her head. “Whatever. Some water would be good.”

“Tia Juana?”

“Black coffee. Just a small one, though.”

“Got it. I’ll be right back.”

I went up to the counter and placed an order, hoping that Ximo would show up and I’d have a chance to talk to him first.

Fortunately, he saw me from the lobby and walked over. But his eyes were looking past me, trying to spot her.

“In the back, with tia Juana,” I said by way of greeting. “Want a coffee?”

He turned back to me almost reluctantly. “Sure. Whatever. . . . Why’s tia Juana here?”

“Bad timing – we ran into her, and AJ and Abuela as we were leaving.” I changed tacks. “Ximo?”

“Yeah?”

“Things were rough, with padre. And when she saw AJ, she collapsed. Fainted.”

That caught him. “Huh? AJ?”

“I know, right? Pretty sure she mistook him for tio Javi. Anyway . . . I’m just sayin’ . . . be a little gentle, okay?”

“Gentle.” He didn’t look convinced.

“She’s got a five hour drive when we’re done . . . I don’t want a car crash on my conscience.”

“Yeah, okay, ’mana,” he said grudgingly. “I’ll try.” He took a steadying breath. “So . . . what’s she like?”

“I don’t know much beyond ‘fragile,’ at least not yet. I guess we’ll find out together.”

Our order came up, and Ximo helped me bring it all to the booth where the sisters-in-law were seated.

I had the stray thought that, given an option, I would never choose to sit with my back to a door or entrance, as they had both done. Momma was pinned against the wall, and tia Juana was next to her on the outside. I distributed the drinks (plus a decent-looking Danish for Momma), then scooted in, leaving Ximo the outside perch.

As soon as we showed up, Momma only had eyes for Ximo – the son she had abandoned when he was in kindergarten. She looked like a doe that had just been shot, bleeding out against a winter backdrop of frozen white.

She tried to speak, and failed.

Ximo’s expression was too complicated to read. Anger mixed with longing, hurt mixed, somehow, with hope. He sat heavily, and when he spoke it sounded like someone had taken a belt sander to his vocal chords. “Momma?”

Tia Juana gave Ximo and me a pleading look. “There are a couple things I needed to say. Mostly for Kathy’s benefit, but for you two as well. We don’t talk enough in this family. Maybe we wouldn’t be so screwed up, if we did. I promise I won’t be long.”

I found myself nodding; Ximo did the same.

“Carmen, when I talked to you at the picnic last month, I told you a bit of what it was like, when your Momma left. I know you’ve heard some other stuff too. It’s been hard for you both, growing up without her. But you’ve got to understand, we made her life hell. We did. I did.”

She turned her eyes to Momma. “That’s what I wanted to tell you, Kath. Why I wanted to stay a minute. I’ve had a lot of time to think, these past years. All those things we used to get so worked up about?” She shook her head. “I mean, after Javi lost his leg, both of us learned just how stupid all that really was. We found out what mattered, and what didn’t. It made me stop and think about who I’d been – and wish I’d done a lot of things differently.”

I noticed that Momma didn’t look surprised about Uncle Javi losing his leg; maybe they’d talked about it together when I was getting the drinks. Or maybe Uncle Fernando had mentioned it in their correspondence at some point.

Ximo said, “I don’t understand. What happened? And why was everyone mean?”

“We were young and stupid, mostly.” Tia Juana shrugged. “From the minute your momma showed up in Buttonwillow, Javi and Angel couldn’t do enough for her. At first, we all just thought they were being nice. She was young, and scared, and pregnant. But it went past that. And your padre was like a volcano, ready to go off any second.”

Again, she gave Momma an apologetic look. “I blamed you for all of it; I know Maria and Consola did, too. Which was always stupid . . . you couldn’t help being beautiful and attractive. If things had been good between you and Juan, I think it all would have blown over. But they weren’t, and so it just kept getting worse.”

As she spoke, some things crystallized in my mind. “You helped her leave, didn’t you?”

Ximo looked surprised, almost shocked, at the suggestion. I could understand his reaction, since tia Juana had always been the sensible one. Grounded. For all she lacked the hyper-religiosity of our other two aunts, she’d always seemed like the most decent of the three.

But I’d guessed right.

She met my eyes and nodded sadly. “Yeah, I did. I drove her and Domingo to the train station in Bakersfield. I’m sorry.”

Ximo’s anguished, “why!” almost broke my heart. He’d only been five when Momma left, and he said he didn’t have many memories of her. But I had come to understand, over the past two months, just how much of a hole she had left in his life. He tried hard — manfully, even — to hide it, but that was a wound that had never healed.

“It’s not her fault,” Momma said quietly. “She did it because I asked her to. I told her I’d disappear. Leave no trace. I was sure that all of you – that all of us – would be better off if I did.”

“It is my fault,” tia Juana insisted, her voice rough with self-reproach. “Not because I helped you then, but because I didn’t help you earlier, when it might have made a difference. It’s my fault for not being a friend, when you needed one so bad. For not confronting my husband when he was acting like a stag in rut.” She looked across the table. “For not doing more for you two, after she left. I tried to, but then, Javi had his accident, and I barely had time to look after my own.”

She looked down at her untouched coffee and grimaced. “That’s all I wanted to say. Except that I’m so very sorry.” She slid out of the booth, rose, and looked down at me and my brother. “Just . . . don’t be too hard on her, okay? You have no idea how bad it was.”

Without waiting for a response, she threw Momma a sad smile, then she turned and walked away.

Ximo shook his head. “She knew. Abuela knew. Uncle Fernando knew. Seems like we’re the only ones you didn’t tell.”

“I didn’t contact Fernando until months later. And I only told your tia and your abuela the day I left. I never told them where I was going.”

“You were that scared of padre?” He sounded skeptical.

“Ximo . . . .” She paused, looking wretched. “I don’t want to bad-mouth your father. Not to you, not ever, and especially not now. But . . . look. It was never right between us. I couldn’t give him what he wanted. What he needed. And it just ate at him like acid . . . wore away everything that was good. By the time I left . . . yes. I was scared.”

“You couldn’t give him what he needed?” Ximo shook his head. “All he needed was for you to love him back!”

She didn’t try to make any excuses. Didn’t plead for understanding.

I respected that.

Instead, she met her son’s scalding accusation with a level gaze, and her quiet response hit like a guilty plea. “I know.”

Ximo abruptly slid out of the booth. “I need a minute,” he rasped. “I’ll be back.”

Momma nodded sadly, and Ximo made his way out of the cafe.

I felt compelled to reassure her. “He’ll be okay. Really.”

She was silent, her eyes lowered.

“I doubt you want to hear it, but you should eat that Danish. Nurse Jill was pretty insistent.”

She didn’t move to touch it; for all I knew she hadn’t even heard me. After a moment, she spoke so softly, she seemed to be talking to herself. “He was always an open book, that boy.” Then she took a deep breath and raised her eyes to mine. “Not like you. I never knew what you were thinking. . . . I still don’t.”

I stalled for time, unsure how much I could trust her. Or myself. “What do you want to know?”

“You must despise me. I would.”

I thought about that, trying to be honest with myself. It didn’t feel right. “No. I think I understand, how you might have felt trapped. And some of what tia Juana was talking about – how bad all of that must have been.”

“Always so cautious.” A ghost of a smile touched her face and vanished. “There’s a ‘but’ at the end of your sentence. There has to be.”

“Sure.” I shrugged uncomfortably. “I can understand, in my head. You. Padre. Abuela. All of you. I can see how my existence ruined your plans. Your lives, even.” I swallowed, trying to loosen the muscles in my throat that had suddenly gone tight. When I spoke again, my voice was brittle. “It’s just hard not to take it personally.”

I could see my words hit her like a flail, but she wouldn’t let herself look away. “It . . . wasn’t like that. Of course I wanted it all – a fun career and friends and a husband and a family and no trade-offs ever. It’s like Juana said just now: we were all young and stupid. When I discovered I was pregnant, though, I found out life isn’t like that. That I had to make choices, and a lot of them were hard. One of them, though . . . . One of them was easy. I chose you.”

“You still left me,” I whispered.

“I know. I know. And I can never make up for that. I’d reached the end of my rope and I just couldn’t go on. Earlier, though . . . I knew that choosing you meant losing my family. I knew it meant leaving school and everything that went with that. I assumed – stupidly, but I did – that it meant moving in with Juan and trying to make that work. The only thing I knew for sure, the thing I clung to like a life preserver, was that I wanted you to live.”

“Your mother wanted you to get an abortion.” I knew this for a fact, so I didn’t make it a question.

“Yeah, she did,” she agreed. “I didn’t want to say that in my letter, but I guess it was pretty obvious. Anyway, she gave me all the arguments about why it made sense. From her perspective, I suppose it did. . . . I could feel you inside me, though. I could feel you moving. Growing. And I just had this overwhelming desire to see you. To know you. The last thing I wanted to do was hurt you.” She stopped, and her smile was rueful. “And look how that turned out.”

It was too much to process, all at once. I needed time, but I couldn’t just take a turn around the block, like Ximo had done. If we both left, she would be gone in a heartbeat. If she can suppress her urge to run, I thought grimly, then so can I.

I don’t know how much of my tangled emotions played out on my face, but she was watching me closely. After a moment, her lips twitched, and she said, “if Juan had gotten his way, I’d have kept having sons. It was like he was in a competition. When Juana and Javi had Miguel back in 2000, Juan was impatient to catch up. . . . But I always wanted a daughter.”

I took a sip of my rapidly cooling coffee to buy me a moment, then asked, “Were you surprised, when you found out?”

“When you called me, I was shocked. It’d never occurred to me. But later, when I tried to write to you . . . somehow, it made a lot of sense.”

I looked at her, puzzled. “When I called you? Didn’t Uncle Fernando tell you earlier?”

She shook her head, and now she looked puzzled. “No. He told me you left after high school, and no-one knew where you’d gone. I thought it was probably good you’d gotten out; Buttonwillow always seemed too small for you. But Fernando didn’t say anything about you being trans.” She frowned. “When did you come out?”

“I didn’t,” I said shortly. “Uncle Fernando outed me.”

“What!!!” She sat back, stunned, and her pale face turned ashen.

“Kelsey found out my secret, way back in Middle School. She used to let me dress at her house sometimes, when Uncle Fernando was out. But he caught me, a couple weeks before graduation.” The sad, shocked eyes. Juan must be told. “He brought me to padre, still dressed.”

“To Juan? Without any kind of warning? God damn that man, what was he thinking?” Her voice rose, baffled, angry, and appalled. “Oh, sweet Jesus! Carmen!”

I didn’t want to share all of that with everyone on the first floor of the hospital, so I kept my own voice dispassionate and deliberately low. “He was thinking like a man, and like an older brother. He felt guilty for having introduced you two, I guess. And guilty that he talked you into coming back after the first time you left.”

Her fury became tinged with incomprehension. “How can you just . . . .” She shook her head, unable to put it into words.

“I’ve had a lot of time to process it. You haven’t.” I paused, trying to decide how much more I wanted to say. How much more she could take. The truth was pretty ugly.

She waited, clearly expecting me to say more.

I tried again. “Look . . . it was bad. It took me two years to get on my feet, down in LA, and I almost didn’t make it. Almost. But I did, and now I’ve got a good life, and incredible friends, and a great job. Even a boyfriend! I can’t let this –any of this – drag me back or drag me down.” I felt my hands balling into fists, and purposefully placed them on the table, palms down. “I won’t.”

She held my gaze for a long moment, then slumped back, defeated. “God, I was an idiot. I thought at least they’d keep you safe. Juan, Fernando. Juana. Even your abuela. I should have been there!”

How many times had I thought the same thing? How often had I silently screamed at her memory, demanding answers that never came? Or, at the very least, an apology? And yet, now that I was sitting across the table from her, the coals that sustained my righteous anger seemed to have burned out. “You said it yourself,” I said after a moment. “You reached the end of your rope. If you hadn’t taken the train, you’d have taken the pills.”

She shook her head, refusing to accept my comfort. “I should have been stronger.”

“We’ve all got a breaking point.”

“Do we?” Again, her eyes searched my face, as if she was trying to find some hidden truth. “It seems like you don’t.”

“I do,” I countered. “And I have. Lots of times. I just had people around who helped put me back together.” Including a second mother, but mentioning that would just be cruel. “You didn’t.”

She looked down at the table, lost in her thoughts and recriminations. When she spoke again, her voice was low and dangerous. “I’ve loved that man for thirty years. I can’t believe he did that to you. And I will never forgive him for it.”

That didn’t seem like a bad idea, all things considered. Loving Uncle Fernando had never done her any good, and had caused a lot of harm. Not to mention the small fact that she was currently married to two other men.

I could have left it there and probably should have, but tia Juana’s words came back to me. We don’t talk enough in this family. Maybe we wouldn’t be so screwed up, if we did.

I sighed. “Well . . . eternity’s a long time. Before you say ‘never,’ there’s something you should probably know. I got it out of him, last time I was up. Never mind how or why.”

She looked puzzled. “You’ve been talking to him? In prison?”

“It’s a long story. What’s important is, he financed the scholarship that paid for Domingo’s music school.”

“No!” Her eyes blazed. “That, I know is a lie. The scholarship came from a charitable foundation.”

“Right,” I said patiently. “But he created a shell corporation to set up the foundation. He didn’t want you to know.”

“But . . . why would he do that?” She sounded genuinely confused.

“He said it was guilt.” I decided I didn’t need to say whether I believed his explanation.

Momma didn’t pick up on my cautious word choice. “Dear God! I don’t get this family! I never understood them!”

“I know how you feel,” I said sympathetically. “But I am trying.” I decided it was a good time to move on, so I said, “I’m thinking we should go find Ximo. I expected him back before now.”

She nodded, almost relieved at the diversion. “Of course. Do you know where he would have gone?”

I slid out of the booth and got to my feet. “Not a lot of choices. If he’s not right outside, I can shoot him a text.”

She scooted out. “Okay.”

I cleared our stuff – no-one had consumed much of anything – and we walked out into the foyer and headed to the doors.

“I didn’t know what to expect, when I saw Juan. What can you tell me about how he’s doing?”

“He was in a coma for a month after the stroke,” I said. “Since then, he’s been making progress. Slow, but I guess steady. He’s at least doing well enough that they’ll move him out of the ICU this week.”

“He seemed very weak,” she replied. “And you said this was the first time he’d spoken?”

“Yeah . . . that was a huge breakthrough. I don’t even know if it would have happened, if you hadn’t shown up.”

“I doubt that,” she said, dismissing the idea.

“You’d be surprised. Every step of his recovery felt like it was linked to you. The first time he responded at all to anything people around him were saying, I was talking to him about having learned that Uncle Fernando had your contact info.”

She shook her head wordlessly. I couldn’t tell whether she couldn’t believe me, or she couldn’t understand padre.

But we’d come to the front door, and I saw Ximo perched on the short sitting wall by the driveway, which was once again in the shade. Just where I thought he’d be.

He spotted us, and rose. When we got close enough, he said, “Sorry. I guess the time got away from me.”

Momma said, “You’ve got nothing to be sorry about. This is all a lot.”

We stood there awkwardly for a moment, then I suggested a walk around the block. Sometimes, I knew, it was easier to talk while doing something else.

They agreed. When we got out to the sidewalk and turned right, Ximo said, “I’m sorry for being so angry. It’s stupid. I know we don’t have a lot of time with you.”

“I’m surprised you’re talking to me at all.”

“I told myself I was angry for padre.” He kept his eyes forward as we walked. “And for Carmen, ’cuz you might have understood her, when none of us did. And all that’s true, but it’s kind of not, too. Like, those are just reasons I should be angry. It’s not really why I am.”

Momma nodded, understanding. “You’re angry because I left you. And you should be.”

“It’d be one thing if you’d just run off,” he explained. “But you didn’t. You took Dom with you . . . but not us. Not me.”

“If it makes you feel any better – and it shouldn’t – I’d have left Dom, too, if he’d been a little older. You two were in school.”

He gave her a sideways look. “Was that why? Really?”

“Yes, really.” She sounded confused. “Why do you think?”

She can’t even see it, I thought.

He stopped, and this time he looked at her straight. “Uncle Fernando is Dom’s father, isn’t he?”

She looked like she’d been slapped. “No!” She was about to say something more, then checked herself. “I’m sorry – Carmen just told me about Dom’s scholarship. I guess I can see why you might think that. But Fernando never took advantage of me like that.”

“You can see why we wondered,” I said, to take some of the burden off of Ximo, though I’d believed Uncle Fernando’s denial. “You loved him, and he at least cared

about you. And he must have been mourning Kelsey’s mom.”

I took Momma’s arm and started walking again; as I’d hoped, Ximo followed.

“It’s my fault,” she admitted. “I guess I keep thinking that you know me better, and of course you don’t. You don’t have any reason to believe I wouldn’t do that. If I hadn’t been married already, maybe it would have happened. Maybe. But I wouldn’t do that to your father, and neither would Fernando. I can’t think of any way to convince you, but it’s true.”

I didn’t want to say anything that might make Ximo feel pressured, so I said nothing. And besides . . . I had a different suspicion, and I was wrestling with whether I should ask about it.

We turned the corner and started walking down D street, one of the short sides of the block that held the hospital.

Ximo continued to walk silently, and it seemed Momma, too, wanted to let him make the next move. The light turned green ahead of us, but all the cars stopped as an ambulance sped through the intersection, siren wailing, heading to the ER.

Finally, Ximo audibly exhaled. “I guess it made too much sense. If there was anything sus about it, padre would have been all over it.”

“You talked to your father about this?”

“No,” I said, breaking in. “Like I said, it’s complicated, but Uncle Fernando told padre about paying for Domingo’s tuition just before he went into prison. Padre was suspicious, but he believed Uncle Fernando when he denied being Dom’s father. So padre insisted on paying back as much of Dom’s tuition gift as he could, even though Uncle Fernando told him not to.”

“So you’re saying your father paid for Dom’s tuition?” She shook her head, completely lost.

“Not exactly,” I said. “But sort of, in a way. Trust me, you don’t want to know the details.”

We turned the corner and headed west on 16th Street. Momma said, “I’m sorry, both of you. But this family just drives me crazy. It always did. What’s wrong with all of them?”

“Fuck if I know,” Ximo growled. “Tell me if you figure it out. I guess Uncle Augui’s okay. And I used to think tia Juana was, too, though after today I wonder.”

“Don’t blame Juana,” Momma said. “I don’t.”

And that . . . that touched on the thing that had been at the back of my mind, ever since I saw her faint at the sight of AJ. I couldn’t think of an easy way to ask the question. “Momma . . . did tio Javier assault you?”

Again she stopped walking, and this time her eyes squeezed shut. Then she looked at me and sighed. “No . . . not like what you mean.”

I returned her look. “How do you know what I mean?”

“You’re wondering if Javi is Dom’s father, aren’t you?”

I nodded, feeling embarrassed. Ximo looked at me, horrified.

Momma said, “No, he isn’t. Javi didn’t rape me; he’s not like that. Please don’t think he is! But . . . .” She paused, shook her head, and groaned. “Damn, this is so hard!”

Ximo reached out and put a steadying hand on her shoulder. “I know tia Juana said it was bad, but . . . this is way worse than I thought. Whatever happened . . . .” He paused, trying to figure out what to say; when he finished, his voice was rough “Just tell us, okay? What’s hard?”

“All of it – just remembering what it was all like. I could handle Angel, usually, even though he kind of creeped me out. But Javi – he was big and strong and handsome. I don’t know if any girl had ever turned him down; it sure seemed like he couldn’t imagine it. Whenever he got the chance – whenever there wasn’t someone watching – he would touch me. My back. My arm. The back of my neck. Sometimes he’d kiss me. I just couldn’t convince him I didn’t want him to.”

“Why didn’t you . . . .” Ximo stopped, knowing the answer to his question before he finished it.

Momma finished for him. “Talk to your father? I couldn’t. He was already so jealous, I don’t know what he would have done. He might have killed Javi. He might have killed me. You have to understand, he just wasn’t rational at this point.”

“I don’t know,” Ximo said. “If I’d been padre, I’d have gone after Uncle Javier, too.”

“That’s part of what made it so hard.” She sounded frustrated by her own inability to explain it. “If Javi had just been a bad man, or, I don’t know, evil or something . . . I think I could have dealt with that. But he wasn’t. Mostly, he was a good man. He was funny, and great with kids. He just couldn’t bring himself to believe that I didn’t want him.”

“I barely remember what he was like, before, you know . . . the accident.” Ximo shook his head. “I can’t even picture it.”

Momma’s lips twitched. “Alejandro looks just like he did, back then. That should give you some idea. But know this, both of you: he may have pressed, he may have pushed. But it never happened. Dom – Domingo – is your brother. Your full brother.”

I thought about Uncle Javi. Both my distant memories of him, from when I was young, and the grim, silent man I knew now. I remembered seeing him in the hospital, shortly after his operation. Seeing the deep lines that pain had etched into a face that had been drained of both color and humor.

I looked across at my brother, trying to gauge his emotions. “Ximo?”

He met my eyes. “Yeah?”

“Let it go, ’mano. Whatever sins he committed, he’s paid for them.”

He looked at Momma, and she nodded. “Carmen’s right. I talked to Juana while you two were getting the coffee. Besides . . . I didn’t come here to stir up old feuds.”

He grimaced, but nodded grudgingly. “Okay. I’ll behave.”

Without saying anything about it, we all started to walk again.

I thought about what Momma had told us. Most people would have said she was a big winner in the birth lottery. Her parents had been well-off. Cultural elites, for sure. And she’d been beautiful – she still was beautiful – and exotic. And vivacious.

What had all of that gotten her, in the end?

We were almost at the driveway to the ER when I said, “So . . . how does it feel, to be Helen of Troy?”

She snorted, then smiled crookedly. “It’s a living, I guess. At least no-one ever came to Denver, burned it down, and dragged me back here.”

I chuckled, but my heart wasn’t in it.

She touched my arm lightly. “I’m sorry. I didn’t know whether to take that question seriously or not. Yes, I’ve had a lot of undeserved advantages, and no, they haven’t been unmixed blessings. I’d like to say I could have done without all the drama, but if I’m being honest, I caused as much of that as anyone else.”

“Are you happy now?” Ximo’s question surprised me.

She nodded slowly. “Yes . . . but I guess I’d say I’ve learned how to be happy. It took me a while – and there were a lot of stupid things I used to believe that I had to unlearn first.”

“You and your new husband – you love each other?”

I wasn’t sure what Ximo was getting at, but I was interested in how she responded.

“We do,” she said softly. “It’s not like I imagined, back when I was in my twenties and I was swooning over Fernando. Liam and I care for each other. Support each other. And I very much want him to be happy.”

I thought about something Uncle Fernando had said, and I felt compelled to push a little. “Didn’t he realize how happy it would make you, if Domingo got his chance to go to that music conservatory?”

She rolled her eyes. “I never should have shared that with Fernando! I was just venting a bit, and I shouldn’t have. Look, Liam’s got his blind spots, just like we all do. When he heard how much that school was charging, he got his back up. He thought it was a complete waste of money.” Suddenly, she smiled. “And boy, did Dom prove him wrong!”

We reached the corner and turned north on A street. I asked, “what’s he like? I barely remember him.”

“He’s wonderful! So much talent – and so intense. I don’t know where the intensity comes from, but he is serious about his music.”

She glowed, very much the proud Momma, and I hoped Ximo wouldn’t feel slighted.

“His band has really taken off,” she continued. “They’re actually going to Europe next year!”

I thought about that, and something clicked in my brain. “Oh.”

She caught the note in my voice, and gave me a concerned look. “What’s wrong?”

“He doesn’t know, does he? About any of us?”

She shook her head. “No. I’m sorry. He’s been ‘Dominick Parkette’ since we got to Denver.”

I hated to burst her bubble . . . but someone had to. “If he’s going to travel, Momma, he’ll need to get a passport.”

“Of course,” she said, sounding puzzled. She’d probably never gotten one since she was a kid.

I’d just been through the process, mostly as a way to celebrate the completion of my transition, so I was very familiar with the requirements. “I don’t know how you’ve managed the ID issue all these years” — her slightly guilty look told me I didn’t want to know — “but everything’s got to be 100 percent legit for a passport.”

“We’ve never had a problem with our ID’s,” she said defensively.

“No,” I said sharply. “I’m telling you, this is different. He’ll need a certified copy of his birth certificate. Providing a fake one is a felony. Lying on the application is a felony.”

That got her attention, and again she stopped cold. “A felony?”

“Yeah. He could go to jail for doing that.”

“Oh . . . shit.”

“So, he finds out his legal name is ‘Morales.’ So what?” Ximo asked. “It’s a common name. You wouldn’t have to tell him . . . you know. About us.”

He might as well have said, “about his lowlife siblings.”

She gave him a distressed look. “Ximo . . . I would be so proud to have him meet you both. You are wonderful people, and I just wish some of that had anything to do with me. It doesn’t, it’s just who you are.”

He blinked, trying to make sense of what she was saying. “Then what are you worried about?”

“It’s padre,” I said, making it a statement. “His name’s on our birth certificates, too. I’m guessing Momma’s even listed as “Kathy Morales” on Dom’s birth certificate; they were married by then.”

Momma nodded sadly. “I think Dom will be okay . . . I mean, he’ll be shocked to find out he’s got siblings, and I never suggested his father wasn’t still alive. It’s Liam, though . . . if he finds out, all the deceptions will hurt him. And I can’t see how he could forgive me for marrying him, when I hadn’t gotten around to divorcing Juan.”

“Do it now,” Ximo said, abruptly.

I looked at him, surprised. “It wouldn’t change the fact that her second marriage was invalid.”

“That’s lawyer talk,” he said, giving me a side-eye. “Obviously I don’t know the guy, but I know I’d be a lot less pissed if the divorce just happened late, instead of finding out she was still married.”

“If I got a divorce on record and a little time passed, maybe that would help with Liam,” Momma said slowly. “ She was quiet for a moment, considering the implications, but then she shook her head reluctantly. “Juan can’t handle this . . . it was bad enough, just telling him I wouldn’t be back.”

Ximo grimaced. “We’ll get him through it. I will.” He saw my look and shook his head. “I’m not saying we should do it today, Carmen! But we shouldn’t wait long, either. He frickin’ never let go, and it’s been years. Decades! Momma moved on; she’s built a new life, and she’s happy. He needs to as well. Fuck, he’s almost fifty. I don’t want him to waste the rest of his life, too!”

I thought about that and nodded slowly. “You’re right. I know you are. It’s past time.”

“He may not see it though,” Momma countered. “What happens if he says ‘no?’”

I shrugged. “It’s California. He can’t keep you in the marriage if you want out. I expect it’s easier if it’s done by agreement, but it’s not like you have minor children, and you haven’t shared finances in decades.”

She appeared to think about that, and we started walking north again.

“Would it be public?” she asked.

“Court records are almost always public; I don’t see why these wouldn’t be.” When she frowned, I added, “I know you wouldn’t want that, but . . . it’s not like a notice would get posted someplace in Denver. Why would Liam look here, after all this time?”

“I guess.” She walked a bit further, her head down, then continued in a quiet voice. “I hate to hurt Juan more than I have already, but . . . we’ve been separated for so long. I would really like to have the marriage formally ended. I’d feel better. Less dishonest, I guess, though that’s pretty stupid at this point.”

Almost reluctantly, I said, “Even Dom wouldn’t find out about the divorce, unless he did some research . . . or spoke to padre. You might not have to tell anyone that part.”

“Maybe.” She shrugged. “But I feel like it’s this unexploded bomb, lying there until someone kicks it. I’d like to defuse it first. Besides . . . .” Her voice trailed off.

“Lies wear you down, don’t they?” I said softly. At her startled look, I said, “Believe me . . . I understand that.”

After a moment she nodded. “I guess you would, wouldn’t you.”

We were approaching the parking lot when some wey in a passing car leaned out the window to give a wolf whistle. He shouted something as well, but it was lost in the background noise.

I shook my head and smiled. “Even at fifty, you’re still the face that launched a thousand ships.”

Momma gave me a look that was first incredulous, then bemused. “You can’t seriously think any guy would notice me, when you’re standing here?”

“Huh?”

This time she took my elbow, and steered me into the parking lot. “When I saw you there by your father’s bed, I knew I should slip away, before you noticed me. But I couldn’t. From the moment I found out you were my daughter, I wanted to see what you looked like . . . . I’d dreamed of having a daughter. Brittany and I joked about it, when we were both pregnant. And there you were, in the flesh . . . more beautiful than I ever imagined.”

I felt the heat rising in my face. “It’s the dress.”

She smiled. “It looks good . . . on you.” Stopping by a cherry-red Mazda SUV, she added, “here’s my rental.”

Ximo swallowed. “This is it, then?”

She nodded, torn. “I need to get back.”

“I understand.” I could almost see his barriers going back up.

She bit her lip. “I still want it all, you know. I can’t help that. I promised myself I wouldn’t ruin Liam’s life, too . . . but I’ve missed you both so much. I don’t want to lose you again.”

Ximo looked at me, but I couldn’t interpret the question in his eyes. Turning back to Momma, he said, “maybe we could text sometime? Or FaceTime? I’d . . . .” He swallowed. “I’d really like that.”

“Me, too,” she said. “I’d like that a lot.”

I pulled out my phone, opened an entry, and handed it to her. “There’s another family member who’d like to hear from you.”

When she saw the contact information, she sat down on the hood of her rental, landing with a somewhat unladylike ‘thump.’ “Mom?”

I nodded. “She tracked me down during the conservatorship proceedings. She was desperate to find you.”

“She said she never wanted to hear from me again.” Her voice was faint.

“Eternity’s a long time. Believe me, she changed her mind.” I saw the shadows of a decades-old conflict playing out across Momma’s perfect features, and added, “the only question is whether you have.”

She shook her head. “It should be easy, right? Just . . . let it go?”

I looked at Ximo. “It’s not easy. But . . . maybe it’s worth it anyway?”

She got to her feet slowly and seemed to sway. Ximo was there in a heartbeat to steady her, and as soon as he did, they were somehow in each other’s arms. Momma was in tears, apologizing, and Ximo seemed to be saying it was alright.

Good.

I bent close to my brother and murmured, “Give me a couple minutes; I’ll be right back.” Then I walked quickly back inside, went to the cafe, and picked up a couple snacks, a liter of water, and a large coffee. Taking a guess, I added some milk to it.

When I got back to the car, they had broken their embrace and Momma was dabbing a tissue at her face.

I said, “Promise me you won’t try to drive all the way back to Vegas on an empty stomach, okay?”

“I promise.” She smiled wistfully. “We didn’t have enough time, daughter. Will you tell me your story sometime? The whole story?”

“I’m still writing it,” I temporized.

“You know what I mean.”

I nodded, a bit reluctantly.

She stood there, clearly fearing rejection if she reached out.

Although my feelings were still tangled, the tragedy of her life’s story touched me deeply, and I didn’t have any desire to hurt her. So I handed the snacks off to Ximo and put my arms around her, surprised by the almost shocking delicacy of her bones. I was almost afraid I’d break her.

She seemed to melt in my embrace, but her response was soft and tentative, and her voice was no more than a whisper., “You were always so hard to read . . . and so hard to reach.”

“We’ll have time.” I took a deep breath. “I promise.”

“Thank you.” She broke the hug, then reached into her purse and put on a big pair of sunglasses that looked almost the same as mine. She got into the driver’s seat and lowered the window. “I love you both. . . . and I always will.”

Ximo bowed his head and managed, “Love you too, Momma.”

I said, “Momma?”

She looked at me through her shades. “Yes?”

I retrieved the snacks from Ximo and handed them to her. “Don’t forget your promise.”

“I won’t.”

I stepped back and said, “Vaya con dios, Momma.”

She waved to us both, and drove away.

Ximo stood next to me, watching as her car was lost in the mid-day traffic. Finally, he said, “Helen of fucking Troy? Jesus, you’re a geek!”

“I know,” I agreed. “Want to take your geeky sister to lunch?”

“Does that mean I’m buying?”

“Well, duh.”

He smiled. “Sure. You like Taco Bell?”

“Goober.” I looked at his strong profile, and the eyes that kept no secrets. “You okay?”

“Yeah,” he said after a moment’s thought. “I didn’t expect to be. But yeah.”

“Good.” I found myself smiling as well. “Very good.”

— To be continued

For information about my other stories, please check out my author's page.