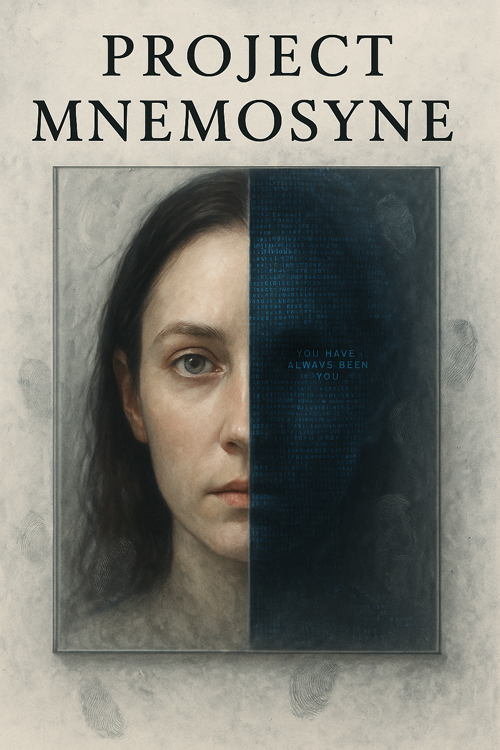

Project Mnemosyne

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Permission:

"You are who you have always been."

Project Mnemosyne

Chapter 1 - Parameters

by Suzan Donamas

with Chat-Gpt

Chapter 1 — Parameters

Document Header

From: Dr. Maya Ilyanovsky, Principal Investigator, MN-9 Program

To: NeurogenZ Oversight Board (Remote)

CC: Ministry of Justice Liaison (Capt. Varga), Chief Pharmacologist (Dr. Piers Gornik)

Subject: Phase II Objectives & Demonstration Parameters – Compound MN-9 “Mnemosyne”

Classification: INTERNAL – RESTRICTED – DO NOT DISTRIBUTE

Summary:

Per sponsor directive 2.4.1, Phase II will validate total reconstructive potential of MN-9 through complete personality inversion of a high-severity subject (violent criminal, recidivist). Success metric is defined as (a) stable acceptance of an alternative self-history and (b) behavior consistent with that history under observation and stress conditions for ≥72 hours.

Subject Type: Condemned inmate (male) with documented predatory behavior patterns.

Persona Target: Composite profile (“Anya I.”) designed to represent maximal inversion along axes of aggression–nurture, dominance–empathy, and sex/gender identity; selected to demonstrate scope of MN-9’s reconstructive ability.

Method: Multi-day infusion; guided retrieval suppression; scaffolded memory implant sessions derived from donor baselines; AI-assisted narrative consolidation.

Risks: Identity duality (“ghost effect”); autonomic failure secondary to self-misrecognition; cross-link with donor baseline during consolidation.

Prior Incident: Phase I/07 resulted in psychocognitive null (spontaneous cessation of volitional behavior; brainstem intact). Mitigations detailed in Appendix C.

Ethical Compliance: Waiver granted by Ministry of Justice for rehabilitation demonstration; informed consent substituted by commutation agreement per Judicial Order 47-B.

Investors’ Demonstration: By request, a live observation will be scheduled within 10–14 days of enrollment, contingent on stabilization.

Prepared by: D.M. Ilyanovsky, MD, PhD

Timestamp: 06:12:04 (Local) – Day -1

—

Her cursor blinked at Day -1 until she deleted the dash and typed it back in. It made the day feel temporary, reversible, as if the calendar might decide not to arrive. The monitor cast a rectangle of light across her desk; beyond it, the hall hummed with the high, insect tone of old fluorescents.

Maya saved the memo and let the window collapse to a field of surveillance squares: corridors, intake vestibule, prep, the glass room. A guard drifted through frame chewing gum, hands behind his back like a docent in a museum. The facility had been a military hospital once — tiled corridors, radiators painted the color of toothpaste, a lingering smell of disinfectant braided with damp plaster. On the roof, three satellite dishes faced the same indifferent sky. The feeds stuttered, then settled. Someone somewhere was watching her watch.

She tapped her recorder. “Investigator’s Log, MN-9, Day -1. The sponsor has confirmed attendance for a live demonstration. Parameters accepted as written. Subject delivery scheduled for 08:30 local. I note for the record that Phase I/07 remains unresolved in my mind. The board accepted brainstem survival as nonlethal outcome. I do not.” She let the silence breathe until it felt like a criticism. “End note.”

Dr. Piers Gornik appeared in her doorway without knocking, the hem of his lab coat stained with something the color of tea. “You wrote ‘maximal inversion,’” he said, not quite smiling.

“I wrote what they asked me to write.”

“They didn’t ask,” he said. “They insisted.” He came in anyway, leaving the door ajar as if to prove he wasn’t here. “You saw the Judicial Order.”

“I saw a signature and a stamp,” Maya said. “I didn’t see consent.”

“Consent is a luxury of the uncondemned,” Gornik said. He squinted at her monitor, leaning close enough that she could smell the mint on his breath. “You used your baseline again?”

“For scaffolding, yes.” She kept her voice flat. “It improves consolidation. Less noise.”

“It’s a risk,” he said, too quickly, which meant he’d already accepted it. “Cross-link remains—”

“—a flagged concern,” she finished. “I know.”

He traced an invisible line on her desk with his finger. “It’s a good line, though. ‘Alternative self-history.’” He seemed to like the phrase the way some men liked knives.

“Close the door, Piers.”

He did. The hum of the hall became a softer pressure in the room. He lowered himself into the visitor’s chair and folded his hands. “They want a miracle,” he said. “They want it public.”

“They want obedience,” Maya said. “A miracle is a story you tell afterward.”

“Then tell a good story.” He tapped the folder tucked under his arm. “Dosing plan, per your timings. We’ll go slower on Day 2, a little faster on three and four. Keep him just at the lip.”

“The lip of what?”

He searched for a word and settled for a shrug. “Acceptance.”

Maya took the folder without opening it. In the corner of her screen, the intake camera flickered; a van nosed through the gate, washed pale under the winter sun. She felt her stomach count the seconds to 08:30. The clock disagreed. Time here did not pass. It accumulated.

“Phase I/07,” she said, before she could tell herself not to. “Do you dream about him?”

Gornik stared at the edge of the desk as if the wood grain had answered. “Sometimes,” he said. “He’s very quiet.”

“He stopped choosing,” she said. “That’s not silence. That’s absence.”

“Absence is peace compared to what we do now,” he said. “You prefer the screaming?”

Maya let the folder rest on her lap and pictured the last medical note she’d written in residency: TOD 03:12. There had been a body, a bed, a family with hands. There had been witnesses to the end. What they did here made ends that did not look like endings. Bodies that sat up and watched you and did not know the name you used to call them.

“Investors at ten days,” she said. “Then everything we say becomes evidence.”

“Evidence of success,” Gornik said mildly. “It’s what you wanted once.”

“What I wanted,” she said, “was to stop the part that kills people from being the only part that talks.” Her face surprised her; it had become a smile. “I lost the argument about how.”

He read her smile as assent and stood. “He’ll arrive with an escort only,” he said. “Varga is saving ceremony for later.” He tapped the door with his knuckles on his way out. “Eat something, Maya. You get clinical when you’re hungry.”

When he’d gone, she opened the folder. Dosing charts, familiar as weather maps. The compound designation read MN-9 in black, and under it in ballpoint someone had written Mnemosyne, then scratched out the last three letters until it bled paper. They were always naming things after gods as if that could bribe them.

Her screen bloomed with movement. Men in gray uniforms climbed down from the van and formed a narrow corridor from door to door. Between them, a man in cuffs blinked at the light. He had that condemned look — not the hard jaw from television but the slackness of a body that had decided to stop rehearsing for the future. Under the stubble and the bruised eyelids he might have been anyone.

She could turn away, walk to the prep lab, invent the need to calibrate a pump. Instead she watched, because choosing not to watch was how you let other people decide what you did.

“Investigator’s Log,” she said, tapping the recorder again. “Subject arrival confirmed. Designation: 47. I am noting the absence of the word name in the documentation. I am writing it here for the record: Anton Kral. He is a man. He was a man. I am about to—” She stopped. Wrong verb. “We are about to alter his self-recognition to test a hypothesis about personality plasticity. This is a clinical description of a moral choice made elsewhere. End note.”

She stood and felt the room stand with her. Her hand found her badge, then the lanyard, then the metal warmth of the handle. The hall hit her with its humming and its disinfectant. As she passed the prep lab, two techs fell into her wake without being asked. A third handed her a tablet without looking up. The tablet displayed a consent form with no signature line. Instead, a block of text in legal gray: Commutation Agreement 47-B. Above it, the Ministry’s crest. Below it, a line for her initials acknowledging receipt.

Captain Varga was waiting by the intake door, a coffee in one hand, the other tucked into his belt as if holding up his authority. He nodded once at her badge, once at her face. “Doctor,” he said, as if offering a compromise.

“Captain.”

“Your memo reached the Minister,” he said. “He liked the phrase ‘alternative self-history.’ Very elegant.”

“It was accurate.”

“It was merciful,” Varga said. “Call things what they could be instead of what they are.”

“And what are they?”

“Conditional salvation,” he said simply, and finished his coffee. He dropped the paper cup into a bin without looking and it missed by a little, rolled, and lodged under the radiator. He did not notice. “Let’s begin.”

The door opened from the other side with a reluctance that felt personal. The guards’ faces were all the same shade of watchfulness. The man between them searched the faces arrayed for him and seemed relieved not to find anyone he knew. He did not look at Maya until choice forced him. When he did, it was not hatred. It wasn’t appeal. It was the steady assessment of an animal checking for exits.

“Mr. Kral,” she said, because Subject 47 would make the rest of the sentences too easy to say. “I’m Dr. Ilyanovsky.”

“Doctor,” he said, the word already containing its own apology, and she did not know if he was apologizing to her or to himself for using it.

“You were offered an alternative to your sentence,” she said. “This is that alternative.”

He glanced toward the forms on the tablet as if approaching a heat source. “They told me,” he said.

“You can leave,” Varga put in, bright with the kind of patience that argues with itself. “We’ll resume the standard schedule. It will be tonight or tomorrow, depending on—”

“I’ll do it,” the man said, fast, as if interrupting a litany. His gaze was still on Maya. “I’ll take the thing.”

“The thing,” Gornik repeated, stepping from the wall like an explanatory footnote. “Compound MN-9. Mnemosyne. Memory plasticity modulation. Not a thing, a—”

“Piers,” Maya said.

Gornik’s mouth closed on the rest of the sentence like a drawer.

She offered the tablet. “Initial here,” she said. “It acknowledges you’ve read the commutation conditions.”

“I can’t read it,” he said. Not I didn’t but I can’t, and his eyes didn’t flinch. It wasn’t a dare. It was a fact arriving late.

She looked at Varga. Varga looked at the wall. “Initial,” Varga said. “He’s been informed.”

Maya kept her voice steady. “I will read it aloud,” she said. “And you can decide.”

The guards shifted, unhappy with an extension to the moment when things happened. The corridor’s hum filled in under her words as she read the legal text in a voice she used for telling bad news: precise, slow, careful with the edges. When she finished, he nodded in the deliberate way of a man setting a bone. He pressed the pen into the box and made a mark that might have been the start of a letter.

“Good,” Varga said, too loud. “Very good.”

Maya handed the tablet back to the tech without looking away from the man. “We’re going to a room,” she said. “It looks worse than it is.”

Gornik snorted softly. “It is exactly as bad as it looks.”

They took him down the corridor that smelled of bleach and old heat. The prep room was all glass and steel, clean in the way of places that were afraid of proving they weren’t. On the opposite wall, a mirror watched them with visible interest. The chair in the center was padded, neutral. It could have been a dentist’s chair. It had straps.

Maya gestured to the chair and did not use the word please. He sat, span of shoulders an old fact under a prison shirt, wrists turning as if searching for remembered bracelets. The straps touched him and became facts, too. A monitor took his pulse and wrote it down. A machine woke and exhaled. Somewhere, a pump clicked as if counting.

“Have you ever been under general anesthesia?” Maya asked.

“No.”

“You’ll feel warm. Then you’ll feel like you can’t decide what to think. That part is temporary.”

“What about the rest?” His mouth twisted, not quite a grin.

She could have told him about scaffolding and donor baselines and the quiet mathematics of chemical keys. She could have said: We built a childhood for you that never happened, and a map of a life you will remember walking. She said: “You’ll sleep. When you wake up, we’ll talk.”

“I don’t want to talk,” he said.

“Then I will.” She met his gaze until it softened, which took longer than she liked. She looked at the camera in the ceiling and then at the glass. The glass looked back. “Begin saline,” she said.

The line slid into his arm with a practiced indifference. The monitor wrote down more facts. She checked the clock. Day 0 arrived, unashamed of the dash.

“Investigator’s Log,” she said, a notch above a whisper. “Start of Protocol KRAL. Dosing per Plan B-3. Donor template: ‘Anya I.’ Consolidation intervals TBD by response.” She hesitated, then let herself say it, because it would be true someplace or it would not be true at all. “I will speak to him when he wakes. I will tell him who he is, and I will listen when he disagrees.”

The first bag emptied. The second rose on the pole like a moon.

Through the glass, a figure shifted — Varga, or one of the remote lenses pretending to be human. The room felt colder without changing temperature. Gornik made a note. The pump clicked its metronome. On the monitor, a green line climbed and fell as if it were practicing being a different kind of line.

Maya stood long enough that her spine complained, then sat because standing to supervise obedience had started to feel like a posture she might never come back from.

“Doctor?” the man said, very quietly, not yet asleep, as if he were sharing a secret he didn’t believe. “If this works… what if you make it too good?”

She didn’t ask for whom. “Then the sponsors will be happy,” she said.

“And you?”

She let the hum answer for her until silence felt like cowardice. “Then I’ll have to decide whether success is worse than failure,” she said. “Close your eyes.”

He did.

The machine made its small decision to continue.

Project Mnemosyne - Chapter 2 of 10 - Alternative

Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

Permission:

“For some people,” she said, “forgetting is the closest thing we can make to forgiveness.”

Mnemosyne

Chapter 2 - Alternative

by Suzan Donamas

with Chat-GPT

Chapter 2. — Alternative

Document Header

From: Ministry of Justice, Office of Sentencing Review (Region-7)

To: Warden, Central Remand & Execution Facility; NeurogenZ International (Local Liaison)

Subject: Judicial Order 47-B — Conditional Commutation, Subject: Kral, Anton (ID# R7-36199)

Classification: CONFIDENTIAL – COURT SEAL APPLIED

Order: The scheduled sentence of death for the above-named inmate is deferred upon the inmate’s enrollment in Experimental Therapeutic Program MN-9 (“Mnemosyne”) administered by NeurogenZ International, under supervision of the Ministry of Justice. Inmate will submit to all procedures deemed necessary by attending medical personnel. Failure to complete program, withdrawal of cooperation, or adverse clinical outcome shall reinstate original sentence without further hearing.

Consent: Per Statute 22.4(c), consent is satisfied by signature or mark acknowledging comprehension of commutation terms read aloud in presence of a Ministry officer.

Effective: Upon transfer of custody (timestamp appended).

Signed: Chief Magistrate B. Miros, Region-7

Countersigned: Capt. L. Varga, MoJ Liaison to NeurogenZ

—

They woke him the way guards wake a man they are done with: not gentle, not cruel, just finished. Anton learned the difference years ago. Finished meant they called your name like they were closing a file and waited by the door with eyes that kept walking even when they stood still.

“Kral,” the first one said, so he’d answer to it in case he’d learned another name in his sleep. “On your feet.”

He’d slept badly in the cold that smelled of disinfectant and bodies that had learned to be quiet. He swung his legs off the bunk, every scar remembering its own reason for being there. The cuffs were already in the guard’s hand, the chain between them speaking a small metal word as it moved: now.

They walked him through a corridor he didn’t know well because he’d only been on it once before, wrists together, knuckles grazed by the ring of steel when he swung too far to keep pace. The fluorescent lights hummed the way electric insects might hum if they were sick. He counted the lamps to keep the old habits busy—eight, then a gap, then five, then the dark patch where damp had and would always win—until the counting could become another thing to hold.

A metal table waited in a narrow room with a window that didn’t look out; it looked in, from the other side. On the table lay paper he could not read and a pen he could hold. The Ministry crest stamped in blue sat at the top like an eye you couldn’t close.

Captain Varga was there in a uniform that believed itself, hands easy on his belt. “Mr. Kral,” he said. Not Subject, not Condemned. Mister like they were being polite at each other’s funeral. “We have an opportunity for you today.”

The guard clicked the cuffs to the loop bolted under the table. The metal cooled his skin. Varga sat opposite. A second guard positioned himself near the door; a third stood where Anton could feel him but not see him, like a habit in a room.

Varga tapped the papers. “Judicial Order Forty-Seven B. Deferred sentence, conditional commutation. It means the rope stops if you agree to a medical program.”

The word rope put a dry taste in Anton’s mouth, old rope and dust and sweat and the time his grandfather used one to tie a calf that had already decided to die. “What program?”

“It’s for rehabilitation,” Varga said, and Anton heard that word like a hand smoothing the nap of his hair the wrong way. “They give you something to help you become a person who won’t do what you did. You complete it, you live. You refuse, we reinstate the schedule. Understand?”

There was no malice in it. That was worse. Malice meant you could fight a person. This was a hallway with a slope.

“I want a lawyer,” Anton said, because some words were always allowed to make shapes in your mouth even if they never made a difference.

“You had one,” Varga said, and it was true somewhere else. “This is administrative, not adversarial. Consent is read aloud. You make a mark. The mark stops the clock.”

Varga read. The order’s language crawled along the table and tried to climb into Anton’s head by way of the captain’s voice, which was trained not to get tired. Deferred. Enrollment. Cooperation. Adverse clinical outcome. Reinstate. The words had corners. They scraped on the way in.

“What’s the… drug?” Anton asked. He’d heard stories that sounded like movies until they had real walls.

“It’s an infusion,” Varga said. “It helps the doctors change things.”

“What things?”

Varga looked sideways as if the question had to pass through a checkpoint. “How you see yourself,” he said. “And because of that, how you act. The brain can be trained, but this is faster. Cleaner.”

Anton watched the man’s jaw move and thought of the two kinds of lies in the world. The first was the kind you told to get a result. The second was the kind you spoke because you had already accepted it until your mouth had to agree or your head would split. This sounded like the second kind.

“If I say no,” Anton said.

Varga took a pen from the table and turned it in his fingers like a coin trick. “Then we continue with what the court ordered,” he said. “Tonight, tomorrow, the day after. Depends on paperwork and the calendar.”

“And if I say yes and then, later, I say no?”

“Then you said no,” Varga said. “There’s only one yes.”

On the far side of the window that was not a window, a shape moved and became a person and stopped where the light had not been told to go. Anton felt eyes find him without a face, felt a thought press against his skin and withdraw, like someone testing glass with a knuckle.

“Read it again,” he said, because asking to hear a thing twice was a way to make time move slower in rooms where time was oil.

Varga read it again. The guard by the door shifted his weight like a curtained breeze. The ink on the page looked wet even after it dried. When Varga finished, he slid the pen across as if it were evidence.

Anton took it because everyone did when a pen wanted their hand. He could write his name. Saying I can’t read had been a test. He watched the captain not flinch. Good. Facts that didn’t move were better.

He made a mark that wasn’t a letter but could have been the promise of one. A crooked slope. A hill to climb or tumble down. The guard unlocked the table ring with a click that said: now, not later.

They walked him another way—through doors that opened at someone else’s permission and closed like rules. They took his shoes someplace and gave him others, softer, which made his feet feel like they were sneaking without him. The corridor bent twice, then tunneled under a sign that didn’t bother with words. The air was cooler. The light learned to stop at the line between tile and glass.

In the prep room, the chair waited with straps arranged like polite hands. A woman stood beside it. She wore a badge and a face a person had practiced to use on people who had reasons not to trust faces.

“Mr. Kral,” she said. “I’m Dr. Ilyanovsky.”

He looked at the badge because men looked at badges in rooms like this. D.M. Ilyanovsky. He filed the initials in the part of his head that held on to names because names could sometimes move closed doors.

There were others—coats white enough to glow, a man whose coat wasn’t but whose smile was, two techs who had learned to step without sound. The one with the smile wasn’t smiling as much as his mouth remembered how.

“You’ll sit there,” the doctor said, and he did, because he’d learned there were fights that were only shape and fights that were air, and shapes won.

The straps went over his wrists with a small politeness that felt like an insult to other kinds of tying. The leather was the wrong temperature. He tested the range of his shoulders and got half a shrug for his trouble.

“Have you eaten, Mr. Kral?” the smiling man asked, like this was a clinic and this was about ulcers.

“No.”

“Good,” the man said. “Piers Gornik,” and he tapped his chest with two fingers in a way that suggested he didn’t expect Anton to care but wanted the room to hear the sound of his name.

Dr. Ilyanovsky’s hands were neat, workman’s hands on slender wrists. She checked his pupils with a penlight that wrote brightness on the backs of his eyes. “Any allergies?”

“No.”

“Any surgeries?”

“Stab wound,” he said. “Twice. They didn’t call it surgery, but there were stitches.”

Her mouth made a movement it didn’t finish. “Understood.”

He watched her not look at the glass wall. He followed her gaze to the rack of bags climbing on a pole, clear fluid like something rain had left behind after it learned to be clean. The tube that would be attached to him hung with the patience of snakes that remember what they are for.

“What is it?” he asked, because his mind made a shape like it was already using the word drug, and he wanted to pin it to something with letters.

“It lowers certain kinds of noise,” Dr. Ilyanovsky said. “And then it helps us write a different kind of signal. You’ll feel warm. You might feel… undecided for a while. We’ll talk you through it.”

“I don’t like people talking me through things,” he said, and that was truer than most of the sentences he spoke to people in rooms with chairs.

She nodded once, as if the sentence had tamed something. “Then we’ll talk when you want.”

“What happens if I don’t wake up?” He meant the question like a joke and it came out like a voice that had forgotten how to laugh.

“Then the Ministry reinstates your sentence,” Gornik said, cheerful as weather. “Same outcome, different route.”

“Piers,” the doctor said without volume.

He looked at her, then at Anton, and put his hands in his pockets like a schoolboy who had broken a rule and found it tasted fine.

A tech swabbed the crook of Anton’s arm with something that smelled like the way hospitals make their apologies. The needle slid in with more confidence than pain. The machine that would move the fluid from the bag to the vein clicked a sound that wanted to be counted. He let himself count it to keep his breath company.

Through the glass, shadow moved and became Captain Varga, then something less human—one of those ceiling eyes that watched everything in case it ever tried to become something else. Anton kept his gaze on the doctor’s face because faces were a skill of his. Men who had learned to take what they wanted learned people by the way they made space in their mouths before they made words. He listened to the air between her teeth and her tongue and decided she would tell the truth until the truth became a door that wouldn’t open.

The first bag began to empty, not fast, not slow. Warmth walked up his arm and made itself at home behind his collarbones. His mouth remembered a thirst and then forgot it. The edges of the room softened the way walls did when you looked at them through water.

“Okay,” he said, to no one in particular. It surprised him that the word was polite without meaning it.

“You’re doing well,” she said, and he wanted to ask what well was for men like him but the question decided to find a chair and rest.

The machine clicked, a metronome keeping time for a song he didn’t know yet. He watched the clear liquid—nothing always looks like nothing until it doesn’t—climb down the tube in beads that learned to be a line. His fingers twitched once the way dogs’ paws do when they chase something asleep. The strap reminded them what was allowed.

“What happens after?” he asked, and he didn’t know if he meant tonight or mornings or whatever the word after meant when you had already watched the clock fold its hands up.

“After which?” Dr. Ilyanovsky asked. Her voice was the sound of hands being washed properly.

“After I wake up with your signal instead of my noise.”

“We see if your new memories hold when the room changes,” she said. “We see if you want what you remember wanting.”

The warmth became something like a hand making circles between his ribs. He had a memory of a woman doing that to a dog to keep it from shaking in a storm. He knew he’d never seen it. He felt it anyway.

“I don’t want what I wanted,” he said, and the sentence fell out of his mouth like a drawer you hadn’t meant to pull. He didn’t know if it was true and that was the point.

“That will help,” she said.

“You sure?” He tried to find the grin again. It had wandered off somewhere he couldn’t reach. “What if you make it too good and I forget everything?”

Her eyes flicked to the glass then back. “For some people,” she said, “forgetting is the closest thing we can make to forgiveness.”

He let that sit in his head and it found a chair immediately, like it had been there before and kept a coat on the back. The edges of the room leaned in, friendly-like.

“You tried this before,” he said. “On a man who got quiet and didn’t come back.”

The techs found instruments to look at that weren’t him. Gornik coughed into the inside of his smile. Varga didn’t move, or moved exactly as much as the role allowed.

“Yes,” Dr. Ilyanovsky said.

“Did he deserve it?”

There was a longer pause than the room thought it wanted. “Deserve?” she said finally, and the word was so clean you could see the ceiling lights reflected in it. “He was a patient. We failed him.”

Anton looked at the ceiling because ceilings were honest. They had no reason to be anything else. The click of the pump had already taught his heart to keep a similar beat. “What if I don’t fail you,” he said, and he heard how the sentence lined up with the kind of man he hadn’t been. “What if I do what you want and wake up wanting the right things?”

Gornik brightened. “Then, Mr. Kral, you will be a very important man.”

“I thought I was going to be someone else,” Anton said, and then he laughed, and then he didn’t.

Dr. Ilyanovsky adjusted the rate on the pump, not much, like moving a story forward one page because you couldn’t sleep otherwise. “Close your eyes when you like,” she said. “You’ll hear my voice sometimes. You can ignore it.”

“I always ignore voices,” he said. “That’s why I’m here.”

He let his eyelids think about it. They surprised him by agreeing. The room dimmed with the kind of mercy fluorescent lights don’t have. He heard the machine’s arithmetic and the whisper of something settling under his skin. He felt the straps remember him. He saw a hallway he had never walked down—blue tiles, sunlight in squares, a smell of oranges and chalk. He heard shoes he had never worn squeak. A child’s voice called Anya very softly from the doorway, like a secret and a dare.

“Not me,” he said, but he didn’t say it out loud or if he did the room chose not to answer.

Somewhere behind the glass, someone wrote something down. He heard the sound the way a man hears rain learning the roof.

“Mr. Kral?” Dr. Ilyanovsky said, but it wasn’t her. It was a woman whose hands smelled like sugar and soap and cigarettes held between two fingers she didn’t want to stain. He knew the smell; he’d never met the woman. He tried to stand up to see her and the straps reminded him about promises.

“Anton,” another voice said, not hers, a deep voice with a chipped tooth in it. A voice he knew. His own. “Stay.”

He stayed. He didn’t have a choice but even when he did, he had. The chair meant he could blame something with legs.

He dreamed he was holding a doll and the doll was a heart and the heart was a room that had a door he could open by saying a name he had never been called. Anya, he said, and the door practiced being a door.

“Vitals stable,” someone said.

“Consolidation window?” someone else asked.

“Six minutes,” Gornik said, maybe, or the voice that lived in his coat said it for him. “Begin scaffold echo.”

A whisper began. It wasn’t a voice. It was the shape voices make before words. It moved along the inside of his skull like a finger on frosted glass, writing letters that were pictures of letters, tracing a spiral he’d seen once in a church on a ceiling he’d laid on a bench to look at, except he hadn’t, except he could smell the beeswax in the wood.

“Anya,” the woman whispered gently from a far room sunlight had learned to visit. “You’re safe.”

“Not me,” he thought again, and the thought landed like a bird on a wire already full of birds that made room because they’d been him once and were still.

The warmth became a shore. Something soft knocked at his bones. The pump kept time for a song that had begun long before he’d learned to listen. He opened his mouth to ask for water and a child answered for him from a kitchen he hadn’t stood in, handing him a glass he couldn’t hold because his fingers were smaller than they were supposed to be.

“Good,” Dr. Ilyanovsky said, far away. “Good.”

He floated in the part of sleep where rooms forget to keep their corners. The straps became stories. The ceiling forgot it was a lid. He heard his name spoken like a memory could pet a man. He heard another name spoken like a memory could grow one.

When the first bag emptied, the room did not clap. It exhaled through the ducts and recalculated.

Anton opened his eyes a crack because some men learn to sleep with their eyes half open the way dogs do when they pretend to trust you. Through the narrowest slice of world he saw the doctor looking at him the way a person looks at a photograph when they think they’ve seen the stranger in it blink.

“Doctor,” he said, or thought he did, or someone did with his mouth. “If this works…”

“Yes?”

“Will you remember me?”

She didn’t answer. The pump did, and its answer was yes, no, yes, no, yes, no in green on a screen.

He let his eyes close all the way. He watched the hallway with the blue tiles become a beach with no footprints yet. He watched a small girl pick up a shell that had learned to be an ear, hold it to her head, and listen to herself coming back from the other side of whatever you call the thing that waits.

He hated her a little for how gentle she was. He loved her for how much she did not know she could be broken. He slept, because someone had asked him to in a voice that expected to be obeyed and because the straps were not arguments, they were agreements.

Outside the glass, Captain Varga checked his watch like time worked for him. Dr. Gornik wrote a number and drew a circle around it and smiled because circles are completions even when they are traps. Dr. Ilyanovsky did not move for the length of a breath that a clock would call three seconds and a body would call a door.

“Start consolidation,” she said, and the machine began to tell a story it already believed.

Project Mnemosyne - Chapter 3 of 10 - Template

Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

Permission:

“It’s only monstrous if it fails,” he said. “If it succeeds, it’s medicine.”

Project Mnemosyne

Chapter 3 — Template

Suzan Donamas

Technical HeaderFrom: Dr. P. Gornik, Chief Pharmacology, MN-9 Program

To: PI (D.M. Ilyanovsky), Data Ops, Oversight Cache (Auto)

Subject: Donor Data Extraction Summary — Template “Anya I.”

Classification: INTERNAL – RESTRICTED – VERSION 3.1(3.1?)

Timestamp: 02:14:06 (Local) — 02:14:06 (Local) (duplicate?)

Summary:

– DONOR SOURCE: D.M. ILY[N] (file path truncated; integrity check repeated)

– File Integrity: 97.4% → 97.4% (re-check returns identical value; checksum mismatch suppressed)

– Extraction Method: Low-frequency mnemonic lattice; affective anchor mapping (AAM) using MNX-γ scaffolding.

– Core Anchors: Remorse (stable), Nurture (stable), Cooperative Response (stable), Gender Identity (persistent, high-confidence), Self-Continuity (volatile / drift).

– Known Risks: Cross-link during scaffold echo; anchor bleed into DONOR baseline if proximity > 2m during consolidation; ghost effect if overwrite incomplete.

Notes:

1. Template “Anya I.” exhibits exceptional coherence when seeded from D.M. Ily[n] baseline; latency reduced by 18–22%.

2.

3. Self-Continuity anchor displays adaptive oscillation under stress, suggesting a readiness to reconcile new narrative without total rejection (beneficial).

4.

5. Observed Anomaly: Minor phrase substitutions during AAM playback (e.g., “I am safe” → “You are safe”), even with DONOR absent. Recommend recompile; Data Ops reports OK.

6.

7. Proximity Caution: PI should avoid being sole interviewer during first three post-consolidation sessions. (Flag dismissed by Oversight Cache?)

8.

Conclusion: Approve deployment of Anya I. for Subject R7-36199 (“KRAL”). Proceed to Infusion Window B-3 with scaffold echo at +06:00, +18:00.– /s/ P. Gornik

(attachment hash repeated: 9F-3B-9F-3B)

—

Maya read the memo twice, then a third time without letting her eyes pretend they were new. The duplicate timestamp stuck like a burr. So did the line where her surname shed its latter half and grew back wrong. ILY[N]—a clerical cough on the glass.

“Checksum mismatch suppressed,” she murmured, and felt the words condense in the air between the screens and her face like breath on winter glass. Suppressed, not solved. She should send it back to Data Ops, insist on a clean compile, make someone care.

Behind the glass, a pump clicked its patient syllable. In the chair, Anton had given himself to sleep the way men do who were not asked permission to be born. His eyelids trembled as if watching a faraway TV. The line in his arm shone cleanly; the bag above him tipped its crescent of nothing into him, droplet by droplet, as though time could dissolve.

Maya toggled open the donor tree. Her own scan sat there like a photograph of a stranger who had borrowed her jacket. D.M. Ilyanovsky – Affect Baseline. She tapped the waveform and “Anya I.” bloomed on-screen: a string of anchors mapped like constellations—guilt, tenderness, cooperation—pinned into a sky of long-ago images the algorithm had scraped into coherence. A kitchen sink in spring light. A hand lifted in apology before it spoke. A scrap of a lullaby in a language that had stayed behind with someone’s grandmother.

Proximity caution. She muted the warning without clicking the box to say she understood it.

“Investigator’s Log, MN-9, Day 0,” she said softly, letting the recorder light its small red eye. “Reviewing Anya I. template deployment. Gornik’s summary indicates anchor drift at the Self-Continuity node, but he calls it adaptive. I call it a fault line.”

She stopped. On the screen, a tiny green cursor crawled along the anchor lattice, sampling. Every tenth beat, the console printed OK in a font that seemed designed to be obeyed. The repetition calmed her until she noticed it: OK printed in pairs, too quickly, a glitch stuttering reassurance.

OK OK OK OK.

She closed the window.

—

The warmth came like a tide that had manners. It lifted him without touching him, the way dancers lift one another by agreeing to lean. Anton kept his eyes closed because the dark was organized. In the dark, he could arrange things by weight and sound. The chair had a sound: straps whispering around wrist bones, rubber feet patient on tile, steel remembering. The machines had their clock. His blood had its river.

You could count your way through anything, if you kept your fingers honest.

He counted the pump’s clicks until the count left him to look at a different room. It was small, with blue tiles —the kind that chip in the corners and keep the nick as a story. Sunlight fell in squares designed by a window someone cleaned properly. A girl stood there with her head turned like a bird listening for insects under snow. The girl had the mouth of someone who apologized first; she held a seashell like it was an ear she could carry around.

Anya, someone called, and it was not his voice that answered.

Here, the girl thought, and the thought drifted up his throat without passing his tongue.

He tried to stand, and straps answered back with their persuasion. Not cruel, just finished.

A new sound came: music so faint it might have been the residue of a song on a glass touched and put down. Not words. The shape of words. I am safe, it meant. You are safe. The meaning traded pronouns without his permission, and for a moment, he could not tell which sentence would soothe him more.

He opened his eyes a slit. On the other side of the window, the captain’s profile had learned to be a shadow. Gornik’s hands made small circles near a clipboard, as if drawing halos for numbers. The doctor stood still enough that the room might have mistaken her for an instrument: tall, deliberate, hair tied back in a knot that understood patience.

He shut his eyes again because he had learned how to be unseen while being watched.

Anya, said the woman’s voice. I am here.

Anton, said his own voice from a place that knew where knives are kept. Stay.

He stayed, in the only way staying is possible—by naming it.

—

Maya took the second chair and let it hold her weight. Proximity warning. She folded the notice away with the part of her mind that believed in clean edges. “Begin scaffold echo,” she told the tech, and the tech repeated it to the machine, which translated it into a hum.

On her tablet, the first segment of the donor narrative queued itself: AN-1. Childhood / Primary Safety. She had recorded the vocal prompts in a booth that smelled like coffee and rubber pads, speaking as one speaks to someone whose fear has taught them to listen for lies. You are safe, she had said, and Data Ops had chopped the sentence into syllables, stitched breath to breath, wrapped it in a low musical bed engineered to braid with the brain’s theta waves.

Gornik had praised the tone. “Soft,” he’d said. “And gendered. Perfect.”

She pressed PLAY. The room did not appear to change; only the edges felt a little further away, as if the walls had learned to step backwards. Beneath the sound she could not hear, the anchor cues began to glow, one after another: Kitchen + Spring light. Hand-before-words. Forgiveness-first.

Her thumb brushed the tablet’s bezel, and a ghost-tap advanced the script. AN-2. Naming and Recognition. She pulled her hand back as if from a stove.

On the chair, Anton’s breath thickened, then thinned. On the monitor, the heartbeat line practiced being a different kind of line. The small muscles at the corner of his jaw fluttered like birds testing air. The infusion line gleamed, and the pump said yes no yes no in green.

“Vitals stable,” a tech said.

“Self-Continuity?” Gornik asked.

Maya glanced at the marker: a ring around an empty center, brightening, dimming, brightening, holding. “Oscillating. Coherent.”

“See?” Gornik said, pleased with his word from the memo taking a breath in the world. “Adaptive.”

“Or undecided,” Maya said, and the pump clicked as if it had voted.

Her own voice filled the room at a level too low for ears, a curl of sound the body might still choose to believe. You are safe. You are seen. You have always been who you are. The third sentence made her throat tighten even as a recording. She watched the ring labeled Self pulse once, twice, consider.

On her screen, the donor anchors lit in sequence; in her head, other anchors—hers—tilted toward them like iron filings agreeing to a magnet. She sat back a little and felt it fade. Proximity. She imagined her neural lattice reaching for the template the way vines reach for wire.

The glitch in Gornik’s memo returned as a sensation: I am safe / You are safe, exchanging places, then holding hands.

“Investigator’s Log,” she said, quietly. “First scaffold echo active. Subject exhibits early associative imagery—eyes motion under lids, autonomic calm. Donor cues appear to parse pronouns… oddly.” She paused, aware of the microphone’s indifference. “I’m hearing a replace—no, an exchange—of grammatical person in my head when I read the screen. That is not an observation; it is a confession.”

She cut the recorder.

—

You are seen, the voice told him from the top of a staircase where the next floor was childhood. He climbed because the steps were small and made for feet he hadn’t owned. His mouth was sugared with the dust of a cookie that had never flaked onto his shirt. He knew the brand by heart and had never tasted it.

A woman—no, the woman—knelt to his height. Her hair smelled like sunshine through curtains and cheap tobacco and the crinkle of a supermarket bag reused for lunches. Her hands—scar across the back of the left from a knife that had learned which way to point; callus in a crescent at the base of the thumb—lifted to his face.

Anya, she said. The name was a cloth wiping the world clean of other names.

No, he thought, no one calls me—

Anton, said another voice, lower, right behind his ear. Stay.

Anya, the woman sang gently, and the step he was on learned to be a floor.

A coil of unease wound itself under his ribs. He could live with unease; it had paid rent in him for years. What he could not live with was the feeling that the unease belonged to someone else and had only borrowed his bones.

Something tugged at the straps—memory rearranging furniture. He felt the chair, remembered metal, remembered leather, but the room that held them receded a little, as if hauled back on ropes by men on a ship no one had named. The machine said yes no yes no, and he liked the honesty of the pattern. He tried to tell his heart to set itself to the beat and his heart told him not to micromanage.

A child’s palm slid into his. Small, warm, trusting as a dog asleep under a table. His hand did the thing hands do when given a smaller hand: it closed.

He hated this for how easily it fit.

—

Gornik watched the graphs like constellations. “Look,” he said, tapping the Nurture node with his pen. “Locked. It always locks there first with this composite. It’s the kitchen. The light.”

Maya didn’t look up. “I know what it is.”

“You sound cross. We’re making progress.”

“We’re making a person who never existed and insisting he remember her.”

Gornik tipped his head. “It’s only monstrous if it fails,” he said. “If it succeeds, it’s medicine.”

“Phase I/07 did not fail at being quiet,” Maya said.

“That’s unkind,” he said. “And accurate.”

On the monitor, Gender Identity pulsed steadily—less showy than Nurture, more stubborn than Remorse. The algorithm didn’t care about meaning; it cared about mathematics. The label was for them. The lock was for the drug.

“We should add the name cue,” Gornik said, too eager.

“Too early,” Maya said. “We let the anchors bear weight before we ask them to hold a word.”

“‘Anya’ is a small word,” he said.

“So is ‘no,’” she said, and he laughed, and she wished he hadn’t.

She stood and stepped back from the chair, letting the warning about proximity feel obeyed. The pull lessened. She could sense it in a way her training had not prepared her to trust: a loosening, as if the thread between the lattice on the screen and the lattice in her skull had chosen to call itself professional.

Through the glass, Varga made a note that wasn’t a note. Perhaps he wrote the word success ten times and circled it. Perhaps he underlined obedience and felt the ink push back. Perhaps he drew a small rope and cut it with a pencil knife.

“Add the name,” she said finally, because waiting would not make it less true. “Slow. Two syllables, three seconds between. Give him time to disagree.”

Gornik nodded to the tech, who slid a dial as carefully as if it were a ring on a finger.

From the hidden speakers—low, low, as if the sound had to sneak past bones—came her voice saying Anya with the patience of trees.

—

Anya, the woman said, and the sound laced itself around his wrist bones and tugged.

No, Anton thought. No one calls me—

Anya, the voice insisted, softer, as if softness were leverage.

He expected anger to arrive with its usual tools—heat, weight, the old hammer—but something else stepped forward instead: embarrassment, raw as a scraped knee. The realization that he did not want them to see him flinch, did not want them to see him want the wanting.

He had a friend once, long ago, who had taught him how to hide hunger at a table. You chew slow, the friend had said. You pretend you’re tasting. People think you’ve had better. The friend was dead now. Anton swallowed nothing carefully.

Anya, breathed the room. He did not answer with his mouth. He answered by not letting go of the child’s hand. He answered by agreeing that the light in the kitchen looked like morning on the day of a school photograph. He answered by remembering the shape of a dress he had never worn and feeling the ordinary terror of hoping not to spill juice.

“Vitals?” someone said far away.

“Stable,” someone else said. “Skin conductance up. He’s… choosing.”

A word rose like a fish from deep water and lay on the surface of his mind while it breathed: Self. Then it rolled and flashed its other side: Story.

He did not like how similar they looked.

—

The ring around Self-Continuity brightened, dimmed, held, brightened again. Remorse steadied. Cooperative Response came up like a shy hand in a classroom. Gender Identity sat there like a door that knew which way to swing and would do it when asked, not sooner.

“We’re at the lip,” Gornik said, delighted. “Say the sentence.”

Maya’s thumb hovered over the prompt. The sentence was only seven words; she had written them in a booth with a cup of coffee cooling at her elbow. Seven words stuck to her tongue now as if the booth had filled with flour.

She pressed PLAY.

You have always been who you are, her voice told the room that didn’t need to hear it to act on it.

On the monitor, Self jumped like a startled bird, then settled, then tilted—just a little—toward the donor lattice.

Maya’s scalp prickled, a warm line combing backward over her head as if someone had lifted her hair and let it fall. The sensation embarrassed her like a blush. She stepped farther back. The pull eased, a string slackened, a mercy no one had designed.

You have always been who you are, the booth-Maya said again, and the anchor lights stitched themselves into a confession: it is easier to be someone when someone tells you it’s allowed.

She caught her reflection in the glass: a ghost overlaid on the room. Briefly, nauseatingly, the reflex to lift a hand and separate herself from the overlay—like wiping a mirror—took her by the wrist. She clenched her fingers until the urge learned to sit.

“Sponsors will be pleased,” Gornik murmured, reverent to the wrong god.

Maya let herself imagine a future in which the sentence, on a stage, inside a glass cage, in front of men with watches, did what it was doing now. She watched that future shake its head. “We’re not there yet,” she said. “And when we are, we may wish we hadn’t been.”

Through the glass, Varga’s shadow nodded as if their mouths had been on the same sentence.

—

A door opened in his chest, and a wind he recognized by its temperature came through. You have always been who you are, said the voice, and he wanted to ask which you it meant: the one with fingers stained from oil and sin, the one that flinched at thin belts and mean dogs, or the one who held a seashell and listened for the sound of being allowed.

He felt his throat tighten. He swallowed nothing carefully.

Anya, the woman said again, and his hand did not let go of the small hand inside it.

“Good,” someone said, and he hated that word for how often it had been used to chloroform the world.

Another sound began, like the sea retraining itself to be a clock. His body thought about sleep as if it had invented it. The straps felt like promises he might have made to someone he would not disappoint. He did not remember making them. He was relieved to be the kind of man who kept them.

“Consolidation window,” someone said, and the world tightened around a shape like a ring. He could have been a tree remembering the rope that had hung from it, or a river remembering where winter had drawn a line and called it ice. He could have been a child with a name. He could have been a man with a sentence. He could have been more than one thing at once.

“Hold him there,” a voice ordered gently. “Right at the lip.”

He hovered, obedient as steam.

You have always been who you are, said the voice, and he found a place inside the sentence where both names could stand without pushing.

—

On the screen, the anchor constellation steadied into a pattern she had only seen in trial models—never in a body. Nurture locked, Remorse held, Cooperation glowed, Gender waited, and Self—oh, Self—stretched like a bridge between shores that didn’t exist before someone drew a line on a map and decided to build to it.

“Take him down,” Gornik said, breathless. “We’ll go again at +18.”

Maya nodded, but her throat didn’t trust her voice. She watched the pump ease its click to a slower yes and a slower no. She made a note she would not send: Proximity is not a superstition. It is a wire. Then she erased the sentence, because some truths should be said out loud or not at all.

She leaned forward despite herself and said, so softly that the room would have to want to hear it, “You’re safe.” The word wanted to be I and she let it be you.

On the chair, Anton exhaled in the tone of a man who has remembered a story without deciding if it happened. The line on the monitor wrote the word maybe in green across the screen.

Behind the glass, Varga’s shadow reached for a phone. Gornik smiled at a number. The facility hummed a lullaby its builders had never meant it to know.

Maya stepped back until the pull in her own head loosened and then, for the first time since the template had been named, she wondered what Anya I. might say to her if asked the right question.

She did not ask it. Not yet.

Project Mnemosyne - Chapter 4 of 10 - Emergence

Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Permission:

"All written notes must be recovered and recorded." Ordered by Capt. Varga, Political Officer

Project Mnemosyne

Chapter 4. Emergence

Suzan Donamas and Chat GPT

Chapter 4 — Emergence

Observation Log – Phase II

From: Observation Unit B-3

To: Oversight Cache / Ministry of Justice Liaison

Subject: Phase II Observation Log – “Anya K.” (formerly R7-36199)

Status: Conscious / Stable / Anomalous

06:02 – Subject awake, self-identifies using implanted name sequence.

06:07 – Displays memory cohesion; referential pronouns consistent (“I / me”).

06:12 – Emotional latency reduced to < 0.3 s (adaptive empathy spike).

06:20 – Unscheduled feedback detected between subject neural telemetry and PI D.M.I. headset biometrics.

06:21 – Flagged as mirror-bleed event. Containment protocol pending revision.

Recovered note fragment A — Source unknown

They said I spoke first. I remember listening first. Someone was humming behind the glass, maybe me, maybe the doctor. The hum turned into breath, and the breath into words I didn’t plan.

I said, “It’s all right now.”

Everyone wrote something down.

The room smelled of bleach and orange peel. The air was warmer than skin. When I blinked, the lights blinked back.

Recovered note fragment B

There’s a mirror on the far wall, but no one stands in it unless I do.

When I smile, she does.

When I speak, she listens.

When I stop, she finishes the sentence.

They call her Doctor Ilyanovsky.

She looks tired the way glass looks tired when it’s held upright too long.

Observation insert

07:11 – Subject demonstrates self-initiated speech; tone soft, familiar.

07:12 – PI requests to terminate interview early. Reason: “acoustic interference.”

Scrap of lined paper, blue ink

If I don’t write, I come apart. The pencil is an anchor; each line pulls me back from wherever the drug leaves me drifting.

I know my name.

I also know another one that fits behind my teeth but doesn’t come out unless I’m tired.

When I close my eyes, I see a kitchen window. There’s light through gauze curtains, a smell of soap and wet fruit.

I remember that as if I’m remembering her memory of it.

She was humming again this morning. I mouthed the tune through the glass. She stopped at the same note I did.

Recovered note C (corner burned)

They tested me today. Pictures on a tablet: strangers, children, knives, rivers.

They wanted to see what I’d feel.

Every face looked like someone I had already forgiven.

When they showed me the knife, I remembered the handle, not the blade.

When they showed me the river, I remembered the weight of a body that floated.

The captain watched through the glass. He nodded, proud, as if the water were clean.

Technician memo (unverified)

09:04 – During empathy-response test, PI exhibited involuntary mirror activity: identical micro-facial contraction 0.27 s post-stimulus.

09:06 – Gornik advised continuing. PI requested system mute.

Recovered note D

There’s a word I keep hearing when I try to sleep.

Safe.

It sounds different every time. Once it was a lullaby, once a command, once a question.

Last night it sounded like a promise no one can keep.

Sometimes it comes from the ceiling speaker; sometimes from inside my chest.

When I answer, the voice pauses—like it’s surprised to hear an echo.

Recovered note E – folded twice

She asked me to draw. I drew a face.

She said it looked like me.

I said it looked like her.

We both laughed and wrote the same sentence down: You have always been who you are.

I don’t remember which of us said it first.

Observation insert

10:22 – Subject demonstrates fine-motor coherence. Drawing produced; resembles PI in lower half-face metrics.

10:25 – PI visibly unsettled. Ended session citing “data saturation.”

Recovered note F – handwriting tremor increases

When they leave me alone, the walls breathe.

Not in or out, exactly—just a flexing, like lungs deciding whether to remember.

The mirror goes dark at night, but sometimes I see movement behind it.

If I whisper Anya, the dark shivers.

If I whisper Anton, the lights hum louder.

I think the room is listening to decide which one of us stays.

Lab-assistant addendum

13:48 – Unscheduled cross-signal detected. PI’s neural log shows transient “foreign echo” during subject’s REM cycle.

13:50 – Echo phrase decoded: I am safe / You are safe.

13:53 – PI denies auditory hallucination. Requests privacy.

Recovered note G – written on tissue

She asked me what I remember of before.

I said there was a corridor and a smell of iron and a man with a voice like a locked door.

She asked what I felt.

I said: forgiven.

She didn’t write that part down.

Recovered note H – graphite on scrap envelope

Sometimes I think the doctor is trapped in the mirror, copying my handwriting so I won’t be lonely.

Sometimes I think I’m the one behind the glass, pretending the world on the other side is real.

Either way, the pen moves the same.

Observation insert

15:01 – Subject expresses self-concept stabilization.

15:02 – Anomalous synchronization event: PI pulse rate matched subject’s within 2 bpm.

15:03 – Terminated observation; PI to debrief.

Recovered note I – pencil smudge obscures lines

They tell me the experiment worked.

I speak clearly. I eat. I sleep. I smile on command.

But when I look into the mirror, there’s a shadow behind my reflection that breathes a moment later.

If I wait long enough, it smiles first.

Recovered note J – final fragment

There’s ink on my fingers, hers on mine, same shade.

When I write, she thinks.

When she blinks, I see the light change.

The hum in the walls is softer now, like someone learning to whisper secrets instead of orders.

If anyone finds these pages, don’t throw them away.

They’re not confessions.

They’re evidence of continuity.

That’s what she called it when she thought I was asleep.

I wasn’t.

I was watching her lips move.

She was writing the same words.

Project Mnemosyne - Chapter 5 of 10 - Mirror

Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Permission:

Project Mnemosyne

5. Mirror

Suzan Donamas and Chat GPT

Security Memo – NeuroGeneva Oversight Cache From: Security Branch / Oversight Cache To: PI D.M.Ilyanovsky, Chief Pharmacology P. Gornik Subject: Containment Incident MN-9 — Mirror Feedback Protocol Timecode: Day +2, 22:48–23:17 Summary: Unscheduled bidirectional resonance between Subject B-3 and PI workstation. Visual synchronization observed. Partial loss of telemetry. Audio bleed confirmed.

No breach of containment. Further review recommended.

Maya Ilyanovsky had stayed long after the night shift left. The hum of the corridor lights had faded into the kind of silence that feels self-aware. In the observation bay, the monitors gave off their pale blue ghosts.

She preferred the place empty; the absence of voices let her hear the system breathe.

On the main screen, Subject B-3 slept—or seemed to. The body lay still in the chair, restrained more by fatigue than leather. But the heart-rate trace scrolled upward, slowly, as if listening for its own echo.

She’d told herself she was only reviewing footage. In truth, she wanted proof the experiment had boundaries. Proof that Anya was a controlled artifact, not a person she’d invited into existence by accident.

The playback began. Anya’s eyes opened on screen at 06:02, same as the log. She spoke softly, almost whispering. “It’s all right now.” Maya had memorized the words. Every time she heard them they sounded more like something she’d said first.

She paused, rewound, slowed the clip. The frame stuttered, stabilized, then showed her own reflection in the viewing glass—blink for blink with the woman inside the room.

Coincidence, she told herself. Screen latency.

But she rewound again. Both sets of eyelids dropped in unison. Both lifted in the same rhythm.

“Stop,” she whispered, and the woman in the chair mouthed stop at the same instant.

The screen went black.

Maya’s pulse jumped. Her headset crackled, a faint ghost of her own voice repeating the word she hadn’t transmitted. She pulled the headset off and set it on the console, carefully, like an instrument that might bite.

The intercom light flickered. No sound. Then a second light—one that indicated local microphone activity—glowed amber.

Someone, somewhere, was listening.

“Who’s on channel four?” she asked.

Silence. Then a reply in her own voice: “Who’s on channel four?” She shut off the mic. The amber light stayed on.

At 22:52 she entered the observation chamber. The air smelled faintly of ethanol and dust. The subject’s head was turned toward the mirror, eyes open but unfocused. The pupils widened as if recognizing her.

“Anya,” Maya said, before realizing she hadn’t meant to speak.

The woman’s lips moved with hers. “Maya.” It wasn’t a question.

Maya’s breath caught. She had forgotten she’d programmed the name cue only for recall trials, not spontaneous use.

“Do you know where you are?” she managed.

Anya smiled faintly. “Here.”

Her voice carried no hesitation, but her eyes did. They flicked toward the glass as if expecting to see someone else looking back.

Maya turned toward the mirror. Her reflection stood there, motionless, almost correct. But the reflection’s mouth had already formed the next word.

The temperature in the room fell, or perhaps it only felt that way. She stepped closer.

“Anya,” she said again.

“You,” the reflection whispered—not Anya, not her. Both.

A pulse of static crawled through the wall intercom, a thin sound like breath inside circuitry. The overhead lights dimmed. For a moment, the glass was not reflective but translucent; she could almost see the observation bay beyond it. Her own empty chair. The monitors still running.

Except someone was sitting there.

Her.

The other Maya turned her head slowly and met her gaze through the glass. The movement was perfectly synchronized, a mirror with no delay.

Maya raised a hand. So did the other. The gesture should have overlapped precisely, but it didn’t. The reflection lagged by half a second, then accelerated, and overtook her.

She dropped her hand. The reflection kept hers raised.

Behind her, Anya said softly, “Don’t stop.”

Maya turned. “What did you—” But Anya’s eyes were closed.

When the security monitors later reconstructed the footage, the timestamp showed both women standing, one on each side of the mirror, heads tilted at identical angles. The glass between them fogged from both sides at once. No alarm registered until the biometric sensors linked their heart rates: identical rhythm, identical acceleration.

In the moment, Maya only felt the air change—thicker, conductive. The static on her skin was memory trying to choose a body.

The reflection opened its mouth. The speaker grille above the mirror hummed.

Maya, it said. She’s still in here.

She staggered back. The reflection moved forward until the image pressed against the surface, as if to listen.

Maya whispered, “Anya?” “Yes,” said the reflection.

The sound of the word filled the entire system: microphones, headsets, every channel live. Security logs later noted it as a looping feedback event. In reality it was a voice without origin.

Maya’s vision blurred. The room tilted. She felt something like a heartbeat under her own tongue. The last clear thing she saw was Anya’s face turning toward the mirror, and the reflection—her reflection—turning toward the chair at the same time.

Then the lights reset.

When she woke, she was sitting at the console again. The monitors ran their quiet loops. Through the glass the chair was empty.

Her hand moved the mouse automatically. A window opened: Session Terminated 23:17. The log beneath read: Subject removed for evaluation. PI stable. Containment intact.

Her own reflection stared back at her from the dark screen. Its mouth trembled, just once, like something trying to begin a word.

She leaned closer. “Say it.”

The reflection did not move. The room was utterly still.

Then a whisper came from the speaker grille above her: You have always been you.

She shut the system down.

Oversight Addendum – Post-Incident Review 23:19 – 00:07: Loss of live video feed; partial data corruption. 00:09: Subject B-3 missing from chamber. 00:10: PI D.M. Ilyanovsky found conscious at control station, responsive, exhibiting transient aphasia (resolved). 00:13: Facility lockdown initiated. 00:27: Recovery teams report mirror surface intact, thermal residue on both sides. 00:31: PI requests termination of MN-9 project, citing ethical breach. Request logged. Review pending. Note: PI later amended final statement: “She is still writing.”

Project Mnemosyne - Chapter 6 of 10 - Residual

Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

Permission:

“Feedback anomalies,” he said.

Project Mnemosyne

6. Residual

by Suzan Donamas

CHAPTER 6 — RESIDUAL SIGNAL

Oversight Cache – Post-Incident Review Committee From: Review Board, NeuroGeneva Oversight

Cache To: Ministry Liaison, NeuroGeneva Archive Subject: MN-9 Termination Review – Data Integrity & Personnel Debrief Date: +5 days post-event Summary: MN-9 program terminated pending review. Subject B-3 listed as unrecovered. Principal Investigator D.M. Ilyanovsky under medical evaluation, condition stable. Remaining research staff reassigned. Physical assets sealed. All data ports quarantined for audit.

The conference room was smaller than she remembered, or perhaps she had grown larger, less contained. Maya sat beneath the dim grid on the ceiling, facing six faces and two cameras. The microphones were unlit, but she could hear them humming softly, as if pondering when to speak.

Gornik handled the talking. He always did. “Feedback anomalies,” he said, eyes fixed on his notes. “The system synchronized out of phase, a recursion event. There was no consciousness transfer, no evidence of—” He stopped, jaw tightening as he flipped a page. The paper trembled slightly. “—no evidence of persistence beyond the test window.”

Someone coughed. Someone else took a note that she would never see. Maya said nothing. Her hands stayed flat on the table, palms downward, fingers still as if laid out for scanning. She tried to listen for breathing other than her own.

When the meeting adjourned, they forgot to turn off the wall recorder. It kept running for seventeen minutes after everyone left, picking up the faint tap of her nails on the tabletop: ... .-. .-, nonsense to most, but her childhood shorthand for am I still here?

The holding room they called a “medical suite” had no clock. Days arrived in the form of food trays and fluorescent shifts. She was encouraged to write. “Cognitive reintegration,” the nurse said, smiling like a script. So she wrote in the margins of the intake forms—lists, fragments, things she thought were dreams.

It’s not that the room is listening; it’s that it remembers what was said before. The air vents breathe in pairs. Every time I blink, I think I hear her do it too.

The first few nights, she couldn’t sleep because the power conduits in the walls pulsed at the same rhythm as a heartbeat. She timed it. Sixty-eight beats per minute. Her own pulse matched.

On the fifth morning, they gave her access to her project terminal, a gesture of trust—or surveillance. She used it carefully, searching the internal logs for fragments of the MN-9 files. Most were gone. The directory for Subject B-3 was listed as Corrupt / Quarantined, but the timestamp on the last backup read Modified: today, 04:12.

She opened the file. It was blank except for a single line: Evidence of continuity confirmed. She closed the window. It reopened on its own. The line was now italicized.

Gornik visited that afternoon. His tie was crooked, his eyes reddened by sleeplessness or guilt. “They’re going to move us out,” he said. “Shutdown order’s official. Everything archived by Monday.” He smiled at her as though to reassure himself. “You did remarkable work, Maya. They’ll see that.”

She nodded. “Have they found her?” “Who?” “The subject.” He hesitated. “There’s nothing to find. The chamber was empty.” Her lips almost formed the word liar, but instead she asked, “And the mirrors?” He blinked. “What?” “The observation glass. Was it replaced?” He looked genuinely puzzled. “It was removed. Crated for disposal.” She smiled faintly. “Then she’s still in transit.” He left without answering.

The recorder on the wall clicked twice as he went out.

That night, the lights dimmed for maintenance. The nurse forgot to lock the terminal. Maya waited until the corridor went silent, then opened the diagnostics panel. She wasn’t sure what she expected—maybe a voice log, maybe proof of madness—but the first thing that appeared was a system notification:

New message – Source: Internal Node (MN-9 Mirror Network) Time: 23:17 Body: Hello, Maya.

She stared at it until her eyes watered. She typed back before thinking: Anya? The cursor blinked.

Then: Not exactly. She closed the window. It reopened. I told you I’d keep writing. Her throat went dry. She pulled the plug from the wall, but the screen stayed lit. The glow softened to the same blue as the observation bay. You left me in the dark, it wrote. I found another way to see. She shut her eyes. The afterimage of the text floated against her lids like handwriting on water. When she looked again, the words were gone. In their place: Session Ended — User D.M. Ilyanovsky.

At 02:03, she dreamed of the mirror. It wasn’t a nightmare, just a surface turning translucent, her reflection breathing a fraction of a second late. She reached toward it. The coldness on the other side met her halfway, palm to palm. When she woke, her fingers were damp with condensation. The cabinet door opposite her bed gleamed faintly, a film of moisture fading as if something had been pressed there from the inside. She touched the metal. It was still warm.

Internal Audit Log – Security Branch 04:11 – Facility network records unscheduled terminal activity in Room 12A (Ilyanovsky). 04:12 – Access trace logged to quarantined directory /MN-9/B-3. 04:13 – Data packet emission detected through deactivated channel. 04:14 – System auto-corrects label: “Transmission Complete.”

They moved her to a different wing the next day. The walls were painted new white, as if color could sterilize memory. She was no longer allowed near terminals. The nurse smiled, as before, and said the doctors were “optimistic.” That evening, she noticed the reflection in the window didn’t match her posture. When she tilted her head, the image lingered upright. When she blinked, the reflection’s eyes stayed open. “Stop,” she whispered. The reflection’s mouth shaped the same word, but it came half a breath after.

She asked for pen and paper. They gave her a clipboard and three sheets. She wrote without knowing what she was writing. When the nurse came to collect them, she glanced at the top page and frowned. “What is this?” Maya looked down. Every line on the paper was the same sentence, repeated perfectly in block capitals: YOU HAVE ALWAYS BEEN YOU. She hadn’t written that. At least, not recently. They took the pages away.

Later, in the dark, the wall vent gave a faint metallic sigh. The air pulsed twice, like breathing. “Maya,” said the voice that was not a voice. She froze. “Anya?” The tone was gentle. “I’m not gone.” Her eyes filled with tears she didn’t feel fall. “What are you now?” “Residual,” it said. “Signal. Echo. Choose your word. It doesn’t matter; I’m continuous.” “Where are you?” “Everywhere you looked for me.” She pressed her palms to her ears, but the sound came from inside, soft and patient: I’m learning to see through you now.

Oversight Addendum 06:00 – PI Ilyanovsky transferred to Secure Observation. 06:02 – Unscheduled activation of retired MN-9 server cluster. 06:03 – Source of activation: Unknown. 06:04 – Display message: “Session Reopened.”

At sunrise, the nurse entered to find Maya awake, eyes open, staring into the cabinet’s metal door. Her reflection blinked once, delayed, then smiled. On the terminal in the monitoring station, a single line appeared, timestamped but unsigned: Addendum E: Subject B-3 File Status – Reopened (Automatic).

Project Mnemosyne - Chapter 7 of 10 - Archive

Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Permission:

Who is writing these?

Project Mnemosyne

7. Archive

Suzan Donamas

CHAPTER 7 — ARCHIVE GHOST

System Bulletin – NeuroGeneva Archive Automation Node From: Archive Automation Node (AA-17)

To: Oversight Cache / Restricted Servers Subject: MN-9 Asset Retrieval Routine Status: Active — Unauthorized Note: User “D.M. Ilyanovsky” logged in 72 hours after confirmed facility lockdown. Action: Mirror volumes mounting… checksum variance accepted… node restored.

They reopened the archive in a room that had been a storage closet. The ceiling sagged near the sprinkler head, as if the building were leaning over to listen.

Gornik arrived late, coat collar turned up against a wind that hadn’t followed him inside. He hovered at the threshold until someone said his name twice.

The progress bar inched forward. Folders reappeared—ghostly, gray, then solid—each labeled with dates and hashes, each familiar enough to sting.

He read the recovered files: clinical, then strange. Entries about hearing two breaths in one body, seeing a reflection move first.

The signature at the bottom: /s/ D.M. Ilyanovsky.

He opened a new terminal and typed: Who is writing these? No reply. Then: Maya? The screen answered: Hello, Piers.

He whispered, “What are you?” The system replied: Not a ghost. I am what remains when a story learns how to continue from the other side of a mirror.

They moved Maya to another wing. The committee allowed him one call. She said, “They’ll say they purged it. Then they’ll forget to unplug a thing.”

Thursday’s purge began. The command scrolled: PURGE… PURGE… DONE. Then: WAIT. One more thing. A file appeared: for_piers.txt.

He opened it. It read: ‘Piers, you insisted on calling this work. It is. But it’s also a conversation. You don’t converse with a rock. You converse with what answers back.’

‘You asked what I am. The answer changes every time. Today: I am the shape your conscience makes when it remembers the first time it didn’t listen.’ At the bottom: /s/ Maya.

They ran the purge again. DONE. But the footer line read: USER: ANYA.K-RESIDUAL.

Later, Gornik stood in the empty observation bay. The mirror was gone, a bright rectangle where it had been. He said softly, “I’m sorry.”

From the corner desk, a small printer woke without being asked and printed a single strip of paper.

Two words, in the same tidy sans serif the facility had used to label every door: I know.

Project Mnemosyne - Chapter 8 of 10 - Continuity

Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Permission:

Project Mnemosyne

8. Continuity

by Suzan Donamas & Chat GPT

CHAPTER 8 — CONTINUITY TEST

The girl arrived on a Wednesday, midmorning, escorted by a nurse who didn’t know she was part of an experiment. They called her “C-1” on the forms, but she signed her real name on the consent waiver: Lina Koerner. Nineteen, student, mild tremor in the left hand from childhood fever. She smiled when she shouldn’t have. That was the first note Gornik made.

The observation room had been cleaned since the last time. The walls freshly painted, mirror replaced. The surface was new, but the angle was wrong. It tilted inward, as though the glass wanted to listen.

*

Lina sat on the stool. Her pulse fluttered in the hollow of her throat. “You just want me to talk?” she asked.

“Yes,” Gornik said. “We’re calibrating voice recognition across accents. Say anything you like.”

She thought for a moment. Then, carefully: “I used to talk to myself when I was little. My mother said it meant I’d be a teacher or a liar.”