Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

Permission:

Queen's Gambit - Chapter 7

© Copyright 2025 Maeryn Lamonte

“Situation resolved, Peter,” Mr Cavendish said. “Perhaps you’d make sure Gwen is looked after. She has no homework for a couple of days at least.

“Thank you, headmaster. Gwen, you’re welcome to come home with us today, and bring Lance with you if you wish. We’ll manage somehow.”

Too many guests at too short a notice meant takeaway, at least enough to supplement what was on offer, which turned into a very pleasant meal. We didn’t stay long afterwards. With the stress, I was very much inclined to have an early night.

The following morning started with a commotion outside the college’s front entrance where Quentin Girling was being refused access to the school.

He’d brought a crowd of tame reporters with him and was declaring loudly to them how he had lost faith in the college and was withdrawing his son from the institution.

Mr Cavendish interrupted Lance and me at breakfast, apologising and asking if we would come with him, at which point he addressed the reporter’s and explained the situation.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he addressed the reporters. “I’d like to introduce you to Gwendolyn Llewellyn. She is our most recent addition to the school, having won herself first a place on a creative writing course here at Marlborough, then a publishing contract for her competition submission, and finally a scholarship to the school as an outstandingly gifted and talented student.

“During her short stay with us over the summer, she won the hearts of not only many faculty members, but also that of Lance Girling here, and a young romance appears to be flourishing.

“Mr Girling appears not to approve the match his son has made with young Gwen, and in an effort to disrupt their relationship, he engaged the assistance of a number of members of staff who proceeded to make Gwen’s life a misery this week.

“Those staff members have been dealt with as an internal matter, and in order to safeguard our students, I have had to take measures to ensure neither Mr Girling nor his wife have unsupervised access to the site and staff. Their actions, Mr Girling’s in particular, show a degree of prejudice and flagrant abuse of position and privilege that this school has no desire to promote amongst its students.

“I had hoped to deal with this matter quietly in order to avoid disrupting our student’s education, but since you have been invited, I see no reason to resolve it with you present. Mr Girling is, I believe, here to withdraw his son from the school. As headmaster, I must openly advise against disrupting his education at this late stage and I am making a formal invitation to Lance that he may remain in the school for now and until such time as these matters may be resolved.

“It is not my habit to do so, but since they have expressed a willingness to participate, I am prepared to allow limited and supervised questions from the press to these two students who have been caught up in this unfortunate affair.”

So Lance and I responded to a string of questions with Mr C vetoing quite a few. It didn’t last long, ending with Lance refusing to leave with his father who then drove off in a temper.

He came back the next morning, which meant the headmaster sent for Lance and the three of them spent most of the morning shut away in Mr Cavendish’s office.

I was too worried to concentrate so, after a short, abortive attempt to work on my remaining catch up work – maths AND science, so working brain required – I gave up and climbed the mound. No-one was there so I spoke out loud, “Merlin, please, I could do with some company.”

He appeared beside me but said nothing.

“Lance’s father has come to try and take him away from the school.”

“I know. I’m not without eyes. Just because you cannot see me does not mean I am not there.”

Too many negatives to unravel this early on a Saturday morning. “What?”

He sighed irritably. “I may not always be close, but I am most of the time. Even when you cannot see me, I will usually be close by. I have been aware of the events of the last two days.”

“Can you find out what’s going on in the headmaster’s office?”

“Where do you think I was when you called to me?”

“Can you influence what happens?”

“Three strong minded and angry individuals. It won’t be easy.”

“I don’t care about easy. Can you do it?”

“That will depend on the outcome. Since I suspect you wish Lance to remain in school, that will be difficult.”

“Then please, go and do what you can.”

“If you still require company, I believe you will find Polly in the library, struggling with an essay that Mr Lee set you earlier this week.”

“Why’s she doing that?”

“Mr Lee is a lazy and somewhat vindictive individual. After his dressing down in front of the head on Thursday, and given that he was no longer permitted to give you additional work, he sought and found a suitable target in your friend Polly. He has only a few pieces of extra work he issues as punishment, hence she is doing the same as you.

“If you go to her there, you will be easier to find when I have news.”

“Okay, thanks Merlin.”

He vanished without saying another word.

Polly was in the library looking very stressed since none of the books held much in the way of relevant information and even her searches were drawing a blank. I’d encountered the same problem until I’d started using AI searches with specific names and dates.

There was a vending machine outside the library. I paused long enough to buy us a couple of hot chocolates, then fired up Lovelace and accessed the reference list from my own essay, taking her down to the relevant parts of each page and showing her the bits of information she needed.

Old fashioned institution with old fashioned rules. We weren’t allowed to speak, but you don’t need words to email over a list of web sites and scroll through them to the necessary bits, nor did you need words to smile with gratitude.

It kept me focussed and distracted from events taking place elsewhere, so it came as something of a surprise when Merlin appeared, and a quick glance at my smart watch – I’ve mentioned that haven’t I? – only to find it was getting on for half past noon.

“They’re done,” Merlin said. Out loud, not that it mattered since I was the only one who could hear him. “Lance is looking for you on the mound.”

I nodded in acknowledgement then squeezed Polly’s arm, pointing at my watch. She was in full flow, typing out her version of the essay, and waved me off with one more grateful, toothy smile.

I caught up with Lance just as he reached the path above the grotto. He paused when I called him, and we climbed the steps together.

“And?” I asked once we’d reached the summit.

“We have a reprieve until Christmas at least. Dad’s already paid this term’s fees and they’re non-refundable. He’s using my lack of academic achievement as a reason for pulling me out, which is a crock of shit; he’s always been about this being the best possible place to rub shoulders with the future rich and powerful. You know Kate Middleton came here?”

I nodded. I mean who doesn’t? Who here at least. “So future kings and queens etc.”

“Yeah. Anyway, if I can show a significant improvement by Christmas, he’s agreed to let the whole thing slide. Mr Cavendish lifted the access ban, saying he felt yesterday’s interview with the press was enough of a response to what Dad did, but he did say if Mum or Dad or anybody else tries something similar in the future, he will involve the law and see whoever messes with this school prosecuted to the fullest extent the permissible.”

“Well, that sounds like it could have gone a lot worse.” Merlin was there again. I mouthed a thank you over Lance’s shoulder at him. “What say we get some lunch and try to work through some maths together this afternoon?”

“With Polly?”

“I think it would be good if we had a go on our own. She’s had a bitch of a morning anyway.”

“You did say you would return to Silbury Hill to hear Nimue’s story,” Merlin said.

“Do you know where I could get hold of a bike?” I asked Lance.

“Buy or borrow?”

“Either. Buy. I think I might want to get out and about a little more.”

“There’s a bike shop on Kingsbury Street. We could go there after lunch before doing the maths.”

“Are you trying to get out of making those significant improvements?”

“No, of course not. I mean I doubt it’ll take more than an hour. We’ll still have all afternoon. Just, I think he closes early on Saturday.”

“It’s a plan. Lunch, bike shop, maths.”

“Then relax in the evening. I mean after the week you’ve had, you need to switch off for a bit.”

“Yeah. Do you have a bike?”

“Never needed one. I could borrow one though.”

“That would be good. It’d be nice to go places together.”

“How about tomorrow?”

“Actually, I was planning to cycle over to Avebury tomorrow.”

“On your own?”

“Well, yeah, why not?”

“You’re a girl. Wouldn’t it be dangerous?”

I hadn’t thought about that. Another degree of minor suckage related to being female. “Okay, so borrow a bike and come along. You may find it a bit boring though. I was planning on sitting out at Silbury Hill for a while and seeing if my muse will sing to me.”

“I don’t know what that means.”

“And you with the classical education. You know, nine Greek goddesses who are supposed to be the source of inspiration for literature, science and the arts?”

“Oh yeah, them. Well, I don’t mind coming. I just like being around you.”

“Okay, assuming we can sort us both out with bikes, we’ll do a picnic and head off to Silbury Hill tomorrow morning.”

It ended up costing more than anticipated, but it was a Pegasus which pleased the classicist in me, and it was an e-bike which pleased my weedy legs. It also had a step through design meaning I could wear a skirt with it, something I’d always wanted to do.

Meaning it had cost significantly more than two thousand quid instead of the anticipated less than one – and even then it had been on offer. I felt compelled to invest in a decent lock, forking out an extra two hundred on it, and a pair of panniers which the salesman kindly added at no extra cost.

I rode it back to the college slowly with Lance walking beside me. The battery needed charging before I could use the electric side of it, which made it a little heavy as bikes went, but manageable. With electric assist I was promised a range of over a hundred miles.

Reception provided me with a key to the locked bike storage area and suggested I might like to use my own lock to secure it too, which I did, carrying the hefty eight hundred Watt hour battery in for its first feast of electrons.

See? That's what doing the extra science homework does for you. I know about electrons and stuff.

Lance had already arranged to borrow Barry’s, a very lightweight looking racing bike that probably cost more than mine. Mine, being sturdier, with motor assist and a carrying capacity, meant I would probably end up bringing the picnic, but since I expected to have Lovelace on board as well as my booster battery, I didn’t expect that to be too much extra burden.

Maths went surprisingly well, considering it involved quadratic equations. Polly had given us a few tips to make it all simpler in our previous session, which we were able to apply and come up with matching answers, except for a few. One where I put the wrong numbers to start with and a couple where Lance’s factorising had let him down. We took one set down to dinner – mine since I was neater – and let her browse through it, getting her nod of approval and a couple of challenge problems to top things off. I don’t know, I’m sure she does this sort of thing for fun.

Sunday was overcast. I’ve always thought calling a day after the Sun was tempting providence, but at least the forecast was dry. I packed a lightweight waterproof anyway. English weather was prone to ignore the weather forecast.

We picked up our pre-ordered picnic lunch from the cafeteria at breakfast and could have been away by eight-thirty if Barry’s bike hadn’t had two flat tires. Not punctures, fortunately, but it took a while to borrow a pump and put air back into them. As a result, we didn’t get away until ten, which meant we arrived at the hill by quarter to eleven.

The observation area was deserted, even mid-morning, but then we were getting a little late in the season. We found a spot out of the way with a good view of the hill and laid out the blanket and food I’d bought with me. Lance reclined along one edge, and I lay down, resting g my head on his stomach, with a good view of the hill. I took Lovelace out and turned her on, then lay back to wait.

“So what happens now?” Lance asked.

“I wait for inspiration. We eat when we’re hungry. One way or another we go home sometime after lunch. If you get bored, give me a little warning and I’ll let you go. Don’t worry, I’ll come back in the light.”

I didn’t have long to wait. Merlin had followed with me somehow and I could already see Nimue walking towards us from the distant mound.

Can you hear my thoughts, I projected at her.

“The lady Gwen wishes to know if you can hear her thoughts as I do,” Merlin said. “I suspect not since your connection with her is not so strong as mine.”

“That’s annoying,” Nimue said. “Can you not speak as you did before?”

Only if Merlin can put my companion into the same sort of trance as my parents, I thought.

“I suppose I could,” Merlin said, “if you’re sure you want me to.”

What would be the harm?

“None, other than he would wake to notice the morning passed.”

I looked at Lance, who was already drowsing. I didn’t think the lapse would be too hard to explain.

“Alright, it’s done.”

“Greetings, Lady Nimue,” I said.

“Greetings and well met, Lady Gwendolyn,” she answered. “Your companion?”

“Like my parents, not sensitive. Merlin has placed him in a deep sleep, I believe. We should be able to talk freely. May I take notes as we speak?”

“I have no objection, though it seems strange to me that you have no quill and parchment.”

“The world changes. Here is my quill and parchment.” I showed her Lovelace with a blank document opened and typed in the words we’d spoken.”

“A marvel.”

“I can speak to it and have it write my words, though it is not so accurate as I would like and unable to hear into the spirit realm.”

“So instead you will write upon it what you speak and what you hear?”

I’d been typing up stories long enough that I could keep up with the spoken word. My fingers skipped across the keys, making mistakes occasionally, but I knew better than to correct them as I went.

“You promised me a story Lady Nimue.”

“I did, and with Merlin here to keep me honest. Perhaps you would care to begin for us, my love.”

“We are no longer lovers, Nimue. I have not considered us such since you imprisoned me at Marlborough.”

“Even so, would you begin the tale?”

“Very well. The Lady Viviane de Gris, as she was named when first I met her, was a creature of rare charm and beauty though, I suspect, little enough innocence...”

“Merlin!” Nimue chided but with a winsome smile.

“You knew well enough the effect your appearance had on the men about you, young or old, fair or foul, and you encouraged the attentions only of those you thought could further your own ends.”

“And is it so very different among men? Even now, do not those possessed of strength or wit or charm use what they have to further their ends? And yet, because I was a woman, I proved myself underhand and false to use that with which fate, or the gods perhaps, had gifted me.”

Merlin scowled. “I served Uther Pendragon at the time. An uneasy ruler who made a practice of riding throughout the lands surrounding his with a show of force intended to intimidate his neighbours and keep them from any ideas of conquest. I travelled alongside him and was introduced as his wizard and advisor. From the moment Viviane heard me spoken of in such a manor, she turned all her considerable charm upon me.

“I was young in those days, or younger at the very least, and not beyond the reach of such flattery. I became enamoured of her and, like an infatuated child, determined to do anything to win her affection, even if it meant revealing my secrets.”

“I also was young and won over by this strange and fascinating man and his promise of magic. I asked him to show me a spell, and he obliged me. Do you recall what you first showed me, Merlin?”

“The Moon was full that night, so I plucked it from the sky and twisted it about in my fingers for a moment, all the while boasting of the nature of magic, and at the right moment I set it back up into the sky.”

“Whereupon I saw the Moon emerge from behind a cloud and knew it to be little more than an illusion. I begged him to show me how it was done, and he revealed the silver coin he held within the palm of his hand. By deft manipulation he was able to cause it to appear and disappear, and by timing it with the clouds moving across the night sky he was able to make it seem as though he could take a piece of the heavens and play with it as a child plays with a toy.

“It was neatly done, but easily enough mastered, and more a trick to please revellers at the feast than any real magic. It delighted me in its simplicity and effectiveness, but in the same instance it also disappointed me to discover that this great magic of the king’s wizard was little more than trickery.”

Merlin grinned wryly. “I could see all too well the dissatisfaction etched upon her face, so I showed her some real magic.”

Nimue smiled at the distant memory. “T’was full winter, with the trees of the orchard standing bare to the wood, and yet as Merlin reached out his hand, a single bud grew upon a barren branch, blossomed and swelled into so ripe and full a peach as you never saw. He plucked it from the branch, and I tasted its sweetness.”

“’Now that is magic I should truly wish to learn,’ she said. I cautioned her that such things always come with a price, that the tree that had born her the fruit would be barren that year for having been coaxed into life while it should have slept, but she begged me, and I possessed no defence against her.

“I taught her a few simple spells, small magic it had taken me years to master, and bade her practice upon it until my return.”

“They proved simple enough,” Nimue said. “In fact so much so that I grew bored and sought to reach beyond them.”

“Against my warning.” Merlin’s face clouded. “I could feel the imbalance growing at a distance of a hundred miles and took to horse in that instant.”

“It was early Spring, and I was impatient for life to return. I had descended upon my uncle’s orchard and immersed my hands within the soil, calling upon such powers as Merlin had shown me and drawing them about me. The grass grew rich under my feet and every tree swelled to full ripeness within minutes. It was a true marvel, but I knew little enough beyond that first sight.”

“I arrived at the keep to find the Lady Viviane in a deep and unnatural sleep, and the fruit in the orchard rotting upon the ground, the trees spent and dying. There was little enough I could do for the lord’s peaches, but for her niece...”

“He remained by my bedside for a week and more, reaching through me into the magic realm, searching for my spirit, calling to it, eventually finding it and bringing it home. We both slept a further week after that, waking together to find my lord's household filled with distress at our long slumber.

“Merlin explained to my uncle what little he had taught me and how impossible it seemed that I should have been able to do as I had. He begged my lord for permission to take me away and train me properly, for fear that I should overreach myself again, bringing worse destruction and perhaps killing myself in the process. My uncle looked upon his decimated orchard and agreed.

“And so Merlin and I began our great adventure. I was an impetuous and precocious pupil, and he needed to rein in my exuberance over and again. He bade me to caution and to learn by his own temperate application of magic, and I did try, though it seemed he was content to crawl like some inconsequential larva, while all I longed for was to transform myself and fly.

“'A candle burned at both ends is soon used up,' he would tell me, and I could only think that a day of true glory must be worth a lifetime of small achievements. The impetuousness of youth, you understand.

“He showed me his boy, Arthur, and through the sight, he showed me the potential within him. He showed me the small tricks he used to grow the young man’s noble character, and in time the greater, though even then he made use of existing magic over that upon which he could draw.

“He forged Excalibur by his own skill and sweat and poured into it what magic he could spare. I offered to assist him, but he would not permit it, asking how I would know when I had given as much as I could spare. I could not answer him, and he asked further how he should seek me in the spirit realm when he was already spent. So I watched and learned.

“He took the sword to an ancient place where one of the stone giants lay and bade the slumbering creature to grasp the sword and hold it until he, Merlin, should ask for it to be release. Through the remaining years of Arthur’s youth, he spread rumour of this sword, that whosoever might draw it from the stone would be the true king of all Albion. I’m sure you know the story.”

I nodded, “Though not in all detail.”

“For nigh on a decade knights and lords came from every corner of the land and beyond to chance their hand. Individuals of unheard of strength, and when they could do nothing to shift the blade even the width of a hair, they began to mutter that the task was impossible.

“Then, upon the lad’s eighteenth birthday, Merlin brought Arthur to the stone. Those gathered about laughed that such a slender youth might chance his arm in such a way, but Merlin called for silence. ‘It is not strength of sinew that will decide this matter,’ he said, ‘but purity of heart.’ He bade the boy step forth and within his mind he called to the giant to release its grip, and so the blade slipped as easily as though being drawn from a scabbard. The boy barely had strength to hold the sword aloft, but all present bowed to him, and I saw how it was that Merlin wielded his tricks to greater effect than might have been achieved by any show of real magic.

“I learned temperance then and, while Arthur grew into his kingship, Merlin taught me to greater effect and we two fell in love.”

“There is truth in this,” Merlin allowed, “though Viviane still showed more of a tendency to expend herself unnecessarily.

“In Arthur’s thirtieth year of life, he set himself against King Pellinore in a duel. He bested the man, as I knew he would, but in the fight, Excalibur was broken. I brought the pieces here and reforged the blade in the fiery breath of the slumbering beast beneath the hill.”

“It occurred to me that simply repairing the sword and return it to the king would be too mundane an act. After Arthur’s near defeat, he needed some sign to show that the land had truly chosen him to rule.

“While Merlin toiled away beneath the mound, I came away to Lake Avalon and made use of my own powers to bind myself to the waters.

“It was a significant expenditure of my strength, but within the balance of all things, as Merlin had taught me.”

“I feared she might be spending herself to no great gain, but I'll admit, she was right to do so. Arthur was despondent. With the Sword of the King broken in his hand, even mended and stronger than ever as I had remade it, he had begun to doubt his right to rule.

“Viviane came to me the evening I completed reforging the sword. She took it from me and hefted it appreciatively. I will say, I never forged a finer blade. It was already a masterpiece the first time I made it, but recast in the heat of a dragon’s breath, the iron seemed to come to life. The balance as fine as any Italian swordsmith might manage and both strong and sharp enough to cut through the horn of an anvil without leaving the least blemish upon the blade.

“’Bring Arthur,’ she said, ‘and meet me at Avalon.’

“It was as much as I could do to persuade him to accompany me, such was his dispair, but he came. A more sullen and silent journeying companion I never knew, so low in spirits that I would swear he afflicted his steed with a drag step.

“By the shores of the lake I bade him call out his name, and so he did. ‘I am Arthur,’ said he with no great enthusiasm, and the lake answered him.”

“As I recall my words, I said to him, ‘Well met Arthur, King of all Britons.’ In binding myself to the lake I could cause its entire surface to speak my words, and so my voice seemed to come to him from all directions at once.

“’How can I be king if I have no sword to show it?’ he answered me, and so I replied, ‘How indeed? Come then and take it from my hand.’ I rose from the lake’s depths with the sword in my hand and held it out to him.

“I’ll give the lad his due, he possessed courage and faith in abundance. He did not hesitate but strode out to me upon the water. Again, it was within my newfound power to hold the lake’s surface steady enough where his feet fell, and so it felt to him as firm as rock.

“I fell to my knees and offered him the blade. ‘Excalibur remade, and now it is a blade fit for Albion’s king.’

“He took it from my hand and drew it from its scabbard, raising it high as though it were little more than a twig.

“’Behold,’ said I, ‘the once and future rightful king of all Briton.’ My meaning that he had considered himself king before his sword broke, and now with it remade, he was once again restored to his throne. I am aware the context of my words has changed with, but there was little enough I could do to prevent it. Once a thing becomes a part of legend, so it stays until all records are become dust.”

“It was in this act that Viviane became Nimue, which in the old tongue means the Lady of the Lake.

“For a great many years Nimue and I guided Arthur and his knights of Camelot, and the peace and prosperity of Albion grew and spread across the land. We had our differences of belief, but for all that, we shared in the common goal of seeing this land united in peace.”

“Perhaps our greatest difference was when Arthur became enamoured of the new religion and began to give thanks for all his achievements to a god that had no part in them. It angered me that he should so readily abandon the old ways, and all the more that Merlin seemed inclined to accept the change as inevitable.

“We began to draw apart, seeing less of each other and speaking only rarely. I sensed a change in Merlin, that he had not the same passion he once had, that Arthur was guiding himself more and Merlin less.

“This became apparent when Morgause appeared on the scene. A woman knows when another woman has evil intent, and I felt it in Morgause from the first. I scried after her past and discovered her to be a half-sister to Arthur, both sharing Igraine as mother, though Morgause’ father was Gorlois of Tintagel, who was killed by Uther Pendragon before taking her to wife and bearing Arthur through their union.

“Morgause felt wronged by Uther and his seed and wished for revenge. Denied any redress against Arthur's father when his daughter Morgana poisoned him, she sought to ruin Arthur instead.

“I tried to warn Merlin, though he seemed distracted and diminished from the man I had fallen in love with. He dismissed my concerns and so allowed Morgause to seduce Arthur.

“The betrayal of his marriage was only one of Arthur’s sins – and yes, I will use the words of the new religion since it is by this standard that Arthur chose to judge himself. In bedding Morgause’ he compounded his evil act in incest, and in so doing created the monster that would destroy him.

“No Questing Beast, for that one was as noble of mind as he was hideous of countenance. No, Mordred, was the beast’s exact opposite. A man of great charisma, though rotten to his soul.

“I still cannot say why Merlin did nothing to stand against Mordred’s reckless ambition...”

“It was more complex than you make it sound. Mordred had no choice in his life, and Arthur tried to do well by him, and in doing so, forbade me to act against the boy. I had already seen Mordred would bring about Arthur’s death, but the king returned my own words to me, that I should permit him to live his own life and learn through his own errors. I had no choice in the matter.”

“That much I did see in you, as much as the fading of your mind which comes with age. I feel certain the younger Merlin would have found a way to thwart Mordred without going against his word to the king.

“Then came the first of the battles that destroyed Arthur, orchestrated by Mordred and achieving little more than the death of a great many Britons and the sowing of seeds of mistrust between the tribes.

“I saw how it tore at you to see your great work rent asunder. I recall you found some solace in the arms of a woman.”

“Gwendolen,” Merlin said fondly

“Yes?” I looked up from my writing at the sound of my name.

“No, this was another of the name, or near enough. It was she who eased the anguish that took me.”

“And she who, for love of you, led you into the mound at Marlborough.”

“She did not endure as I have though. We knew some decades of peace before age took her. She faded from life and lives on only in the depths of my memory.”

“And mine,” Nimue said. “She was a brave soul, and it seemed to me that she could give you what I could not, if only for a short while.”

“But in binding me to the mound you cut me off from Arthur. He might have called to me, and I would have stood by him at the end, for good or ill.”

“But he did not call you, my love. He did not trust you to stand by his son, and you would not, for you saw as well as I that Mordred was rotted to his core. He wished only death and destruction, and he found it, even to the point of receiving his own death blow from his father’s hand.

“After Arthur was mortally wounded, Bedivere brought him to Avalon and, at his king’s bidding cast Excalibur into the lake, where I caught it. I sent a craft of magical aspect and took Arthur’s dying body out to the Island of Avalon, and there both the spirit of the king and his blade remain.”

“The once and future king,” I said.

“No. His time his been and gone. All that remains of him is in the spirit realm, much as Merlin and I are there, although he has not the magic to manifest as we do. He is at peace and will remain so.

“The future lies with you, Gwen, and those of your generation. You have your own battles to fight, and Merlin will stand by you, as, should you will it, will I. This land deserves better than it has, and the world in which it resides needs one to lead it to better times.”

“I don’t see how you can expect that of me.”

“If not you, then who? This is your world, wounded and tainted as it is by those who have gone before, and your choice, just as with those who have gone before, is to sit by and watch it burn, looting the charred shell for anything to make your days easier, or to fight back against the insanity and the selfishness that stands ready to rob future generations of their inheritance.”

“Yes, but how am I to do that? I’m just one person.”

“Are you? You have your knight here who stands ready to defend you against all. You have Merlin’s wise counsel, and mine if you will be convinced to accept it.”

“Will you give me Excalibur?”

“I’m sorry?”

“From the tale you told, you were the last to hold it. Will you tell me you do not know where it lies?”

“I know, but what would you do with it?”

“As I understand, it is the symbol of authority for Albion’s ruler. I have no desire to wield it as a sword – I suspect in our modern world, to do so would be a serious crime – but if I am to take on the mantle of Queen of Albion as I have already agreed with Merlin, would it not be easier to establish my credentials if I held Arthur’s sword?”

She stared at me blankly. Merlin seemed a little unsure of how to continue either.

“You have said you have little inclination to trust your Lady of the Lake. How would it seem as a gesture of good faith were she to return Excalibur to the world, to place it in the hands of your chosen queen?”

“I have to admit, it is a fair point,” he said.

“Would you open yourself to me if I were to do this thing?”

“Let it be a gesture of good faith on your part. Give up the sword and allow me to decide after if I trust you so much.”

“Very well. How would you have it done?”

“I’m sorry?”

“Shall I find Merlin’s rock giant and have him grasp it until such time as you place your hand upon it?”

“I’m not sure that would work so well in the modern world. I expect before long someone will come along with a pneumatic drill and break away all the stone surrounding the sword, with no consideration that they were destroying a fabled creature’s hand.”

“Would you have me ascend from the lake holding it in my hand? What remains of the lake in any case, which is shallow enough.”

“Again, I think it would be seen as a gimmick. Modern technology is no respecter of magic. Besides who would see you?”

“Then how?”

“I beginning to wonder if it’s such a great idea. After over a thousand years it would be so corroded as to be scarcely unrecognisable as the sword it once was.”

“Forged in dragon flame, it will not have corroded in the least.”

“And then who would believe it were over a thousand years old?”

“Do you not have a means of dating such an artifact?” Merlin asked.

“Carbon dating wouldn’t work on metal, only organic materials.”

“Like the leather of the scabbard and the bindings about the grip perhaps?”

“If any remained after such a long time. And what then? A sword that’s unscathed after fifteen centuries wrapped in rotting leather that dates that far back? Who’s not going to believe it’s a hoax?”

“Not rotting,” Nimue said. “Arthur’s coffin is sealed against the elements. No water and little enough air.”

“I thought the monks of Glastonbury found Arthur and Guinevere’s tomb in the twelfth century.”

“It wasn’t Arthur’s grave,” Nimue said. “They missed it by a mile, or thereabouts. Arthur lies beneath Glastonbury Tor. Deep beneath, within the clutches of the White Dragon.”

I turned on the tethering option on my phone and connect Lovelace to it. A quick search showed me pictures of the Tor.

“That’s a mound? Like this place and Marlborough?”

“The first of them as far as we can tell. Too immense to make it round as with these, but it had to be such a size to cover the beast beneath. You buried Arthur there?”

“It seemed fitting somehow. Albion’s greatest king resting with her greatest dragon. The Tor used to be the island of Avalon, at the centre of the lake. My lake.”

“Is there a way in?”

“For those with magic.”

“Oh.”

“Don’t play the fool. You can see and hear Merlin and me. Of course you have magic.”

“Oh.” More enthusiasm this time.

“The challenge will be to get to Glastonbury,” Merlin said. “As I recall, it is three days ride from here. Perhaps as little as one if you don’t spare the horses.”

A little more fiddling with the Internet. “Five hours on bicycle and I’d pretty much drain my battery, or four on public transport. Either way it’s an overnight, which means asking permission and fielding questions. Shame we can’t arrange a field trip. It’s an hour and a half by road, three including the return. That would give us several hours there.”

“Geography, history, music or literature?” Merlin asked.

Nimue and I looked at him.

“It’ll take a while, but I can influence one of the teachers.”

“History then. Mr Lee is a bully. I’d love to spend his budget.”

“Very well. It seems we have accomplished as much as we are able today. Lady Nimue, one of us will let you know when we have a date. For the trip.”

My ghostly companions faded and I squirmed against Lance, who stretched heroically and looked at his watch.

“Shit, is that the time? I must have dozed off. Did the muses sing?”

“Very much. They seemed to like the counterpoint of your snoring. Hungry?”

“Ravenous, and I don’t snore.”

“My apologies. We must have some very syncopated earthquakes around here.

We did lunch and I let him skim through the pages of typing I’d done.

“You got all this just from being out here?”

“Well, it’s a bit more than picturesque scenery. Being here helps me feel my way into the history of the place. That hill was built over four thousand years ago for God knows what reason.”

“Does that make you God?”

“Hardly. Why?”

“Because apparently you do know. It’s a resting place for an ancient dragon according to this.”

“Which is a very rough draft,” I said grabbing Lovelace back from him and snapping her shut. “Not for in depth scrutiny at this stage.”

We ate and lay in the autumn sun until it started to get cold, then we packed up and hit the road. My trusty Pegasus still had three quarters battery life by the time we made it back to the college grounds, and I, at least, didn’t stink like a Turkish sauna while we were locking up our bikes.

“Go shower,” I told him. “I’ll see you at dinner.”

That gave me an excuse to climb the mound alone.

“Am I interrupting?” I said at the summit.

“It would take a matter of considerable importance for me to take it as an interruption.”

“You weren’t that happy last time?”

“The matter of your boyfriend being withdrawn from the school was, to my perception a m...”

“...atter of considerable importance. Yeah, okay, I agree.

“Tell me about the story you and Nimue told this morning.”

“Tell you what about it?”

“You were there to ensure she kept to the truth. How did she do?”

“She told it the truth as well as I recall it.”

“And yet you still do not trust her?”

“I... may have been a little hasty in my judgement. I’m still not sure. My own memories are a little confused. Filled with anger that she should trick me, and a little lighter on my recollections before I reclaimed my intellect under the mound.”

“So, do you think she is with us or against us?”

He sighed. “Will you permit me a while to reflect on the matter. I have other memories to consider, to compare, to see how well today’s exchange matches up with the woman I knew.”

“Of course, only...”

“Only what?”

“From what Nimue was saying, both she and you have the freedom to travel about.”

“We are not confined to the mounds which hold our remains. You know already I can travel with you because I am linked to you.”

“Nimue said she could go back to the lake that gave her her name.”

“Aye, we can journey to places of power, of significance in our lives.”

“So, what kept you from going to Silbury before now, or her coming to you here?”

“For me, some centuries of anger and distrust, I suppose. For her, most likely discretion. You do not pay a polite visit upon anyone you believe bares a grudge against you.”

“She was worried about what you might do?”

“We are beyond harming one another,” he said, “and we neither of us would have considered such a thing in life, but for the most blatant betrayal.”

“Which you accused her of?”

“I did, but no, she was safe enough from me.”

“I like her,” I said.

“Most do. She possesses a tongue of purest quicksilver, as do you. You need only open your mouth and those around you wish to be your friend.”

“I wish that were true.”

“Count on your hands the students you have met since coming here, then count off those you do not consider to be friends.”

I did and of course was left with no fingers remaining.

“I think it’s because we both speak the truth, and people notice and appreciate it.”

“Your observation is noted and will be included in my deliberations.”

“Could you go to Glastonbury Tor and retrieve the sword?”

“Yes and no.” Unhelpful, which I attempted to convey with my expression. “Yes, I can travel to Glastonbury Tor. I have already and seen my friend’s coffin and the sword that lies upon his chest. No, I cannot retrieve it. Magic it may be, but insufficient to counter my lack of flesh.”

“Does it have magic enough to be transformed?”

“You mean into a more contemporary weapon such as a pistol? There would be complications.”

“Not the least one being that it would still be illegal.”

“A bow then. That I could manage, and I recall you possessed some skill.”

“No, I had something else in mind.”

It took a couple of weeks to get the trip to Glastonbury organised. Mr Lee was a non-starter – as much of an arsehole when it came to spending money on his students. The surprise success story in the end was Mr Phillips who was always looking for ways to resurrect his dead language of choice. He happened to mention how many Latin inscriptions and documents there were in and around Glastonbury, after which it didn’t take more than a mental call to Merlin followed by a gentle magical nudge and the trip was promised then organised.

My own life at Marlborough had become considerably easier since the head had called his baying hounds to heel. Most of them appreciated that I’d stuck my neck out for them and turned what would have been career disaster into a minor inconvenience. As a result they let me blend into the background and, as long as I kept up with the general pace of the class, they allowed me to progress at my own pace.

Which gave me a little extra time finally to organise the Friday evening discussion groups. That's all they were to start with, since there were a considerable number of challenges to the ideas I'd proposed. I listened and tried not to use my quicksilver tongue to overrule them. Instead, I tried to adapt my ideals to the realism with which I was presented. By slow degrees we began to form a concept of New Albion.

Incidentally, the name was one thing we still disagreed upon, but that was something for the future.

Of all the teachers, Mr Lee was the only fly in my ointment. He kept looking for ways to mark me down, so I worked hard to make sure he didn’t have any, and that seriously pissed him off. From my perspective, it was a double bonus because it gave me incentive to work at an otherwise dry subject, and I got to rub Mr Lee’s nose in it.

Latin proved to be an unexpected pleasure. Complex, and almost entirely useless, it still proved to work better than maths for me as ‘pressups for the brain’ which my former maths teacher had called the more abstract parts of the maths syllabus. Latin fit in better with my literary aspirations. I was less enamoured of the sing-song affectations with which Mr Philips spoke the language – thank the bloody church for that piece of nonsense – but I did enjoy the challenge.

Glastonbury Abbey had been where twelfth century monks had supposedly come across an inscription which read either ‘Hic iacet sepultus inclitus Rex Arturius in insula Avalonia’, which translates to ‘Here lies buried the famous King Arthur on the Isle of Avalon’, or ‘Hic jacet Arthurus, rex quondam, rex futurus,' which we were given the task of translating and came out as ‘Here lies Arthur, king that was, king that shall be.’ A once and future king reference. Since the monks had carelessly lost the original inscription, neither text could be corroborated, and here was just another example of how big a bunch of ‘lying arseholes’ – Mr Phillips’ term not mine – medieval scholars could be.

We left early, immediately after breakfast, meaning that an hour and a half’s drive had us arriving at the Abbey in Glastonbury around nine. We spent the morning using our phones photographing as many Latin inscriptions as we could find and working in small groups to translate them as best we could. Mr Phillips went between the groups, commenting on the grammar and syntax of the inscriptions we’d found, usually criticising it with some comment about the monks having worse grammar than we did. I didn’t take it as much of a compliment. I mean okay, Latin’s a dead language so it won’t have changed much, even in eight hundred years, but thinking about Shakespeare’s inconsistency in spelling just four hundred years ago and the near incomprehensibility of Chaucer’s writing at six hundred years, it felt like the monks were doing well to come up with something even vaguely recognisable after eight hundred.

Still, not my place to comment.

Lunchtime approached. I asked Mr Phillips if it would be possible to have time to go over to the tor, which my phone suggested was about a half hour walk. The bus service wasn’t great and wouldn’t take any less time. I was the only one who wanted to go – too much effort for too little gain for most – so he agreed to let me go half an hour early, but still to be back by one.

I thanked him and broke into a jog as soon as I was out of sight.

Running, I managed to shave few minutes off the anticipated transit time, then when I reached the hill, Nimue and Merlin were waiting for me at the base, which apparently was going to save me the climb. I’d made it in just twenty minutes instead of the expected thirty-five.

“We have just less than an hour before I should head back.”

“And if it takes longer?” Merlin asked.

“Then I’ll be late getting back, and if I’m very late Mr Phillips will probably involve the police. I’ll be in trouble whatever happens, but if it goes that far, I’ll be in it up to the tip of my nose.”

“Well, the sooner we start, the sooner we’re done,” Nimue said. “This way.”

I followed her around the base of the hill towards the north until she came to a halt beside a steep, grassy slope that looked exactly the same as the slope we’d been walking past.

“When you speak to Merlin with your mind?” she asked. I mean it’s not really a question, but she did the rising inflection thing at the end that said, ‘here lies a question mark.’

“Okay?” I did that same back at her to see how she liked it.

“Look here but use that same part of your mind.”

It was actually surprisingly easy. I focused my mind and tried looking through it instead of directing my words, and there it was, outlined in a ghostly light. A doorframe with a Latin inscription.

It was, word for word, what twelfth century monks claimed to have found. I read it out loud, avoiding the ridiculous sing song version, and nothing happened.

“Now come over here,” Nimue led me round a ridge in the hill and there was a hole in the ground.

“It’s how magic works in the modern world. Too much scepticism for it to be seen to work overtly, but the entrance would not have been there if you had not read the inscription, or if you had done it wrong.”

“It doesn’t look much bigger than a rabbit hole,” I complained.

“More a badger’s sett, but agreed. We wouldn’t want the tourists to see a large gateway and come wandering in after us, would we?”

“You’re paying my dry-cleaning bill,” I said.

“Alright.” He handed me a coin. It was roughly shaped with a Roman looking face on it.

“Is this...”

“A Roman aureus. Gold. I believe that’s Augustus on this side.”

“Where did you find it?”

“I didn’t find it. I brought it with me when Gwendolen led me into the mound.”

“It must be worth...”

“Enough to clean your uniform at least, now can we stop wasting time?”

I glanced around, but the only other people I could see were Merlin and Nimue. I dropped onto my knees and squirmed into the hole. If I should get stuck, I would be in all sorts of trouble, but I was slim enough and the narrow tunnel only continued for fifty odd yards before it widened, and another fifty beyond that before I had room enough to climb to my feet.

Have mobile can see in the dark. I turned on the torch function and looked around me. The cavern, assuming it actually deserved the title, consisted of chalky soil held together by a root system of sorts. It was difficult to imagine what on the surface had roots that reached this deep, but it didn’t really matter.

Nimue appeared beside me making the cramped space positively claustrophobic, and led me down a tunnel. There were several, so I had no idea which to choose. Even focusing my sight gave no clues.

She led me through a maze of twisty little passages, all alike. And I mean seriously, if there was a sequence to get through it, I wouldn’t have known how to apply it. Most of the time I couldn’t tell my down from my west, and which way was north in the first place?

Ten minutes to find and open the cave, fifteen minutes to negotiate it. We were approaching the halfway point for my lunch break when we turned one last corner and the space just spread out around us.

The place was so immense my torch couldn’t make out the far side, and it was filled with a deep, steady susurration and an unpleasant whiff of sulphur.

“Kilgharrah the Great White Dragon,” Nimue said in hushed tones. “She hasn’t woken in five thousand years so no cause to believe she will now, but best to move cautiously. Douse that light and use your mind’s sight to see your way.”

Not how I would have chosen to proceed, but I trusted her. The phone light went off and into my small rucksack purse. I focussed again and looked.

The extent of the cavern was immense, as was the creature filling it. With her tail and snout wrapped into a tight circle, she still must have measured forty feet across.

Nimue’s ghostly arm pointed within the monster’s grasp where a coffin lay, carved from ebony or onyx with bas-reliefs of some pretty hair raising sword fights covering the sides. From a distance it actually looked like Arthur had been laid on top the coffin with his sword grasped in his hands. As I drew nearer, it became evident that the figure laying on top was only a carving, while the sword...

Built for business, it was not a particularly attractive sword. Straight and double edged with a handle big enough to accommodate a large hand. If the figure carved on to the coffin was any measure, Arthur appeared to be a few inches shy of six feet, yet if he’d held the sword by his side, the tip would most likely have reached the ground. So what does that make it? Blade length from mid-thigh to the tip of a pointed toe.

The blade was exquisite. Unadorned other than an inscription which read ‘suscipe me’ in angular letters.The a blade width from sharpened edge to sharpened edge was not much larger than the width of my hand not counting the thumb.

A scabbard of oiled leather lay beside the stone knight, but his hands grasped the weapon’s hilt firmly enough to cause me to doubt whether I might prise it loose.

I let out a sort of huff of a laugh and stepped gingerly over the dragon’s tail, then around a snout as long as my body. I placed my hand upon the sword and the heavy breathing filling the cavern ceased.

A movement caught the edge of my vision and from the corner of my eye I saw a glint of ghost light reflected in an eye as large as a dinner plate.

“Your majesty,” I said quietly, unsure whether I addressed the dragon or the coffin, “Albion has need of Excalibur once more. Will you permit me to take it?”

For a heart stopping moment, nothing happened. Then the stone knight’s hands relaxed and the blade slid free into mine. The eye beside me closed and the breathing resumed. I picked up the scabbard and stepped quietly away from the sleeping dragon, out of the giant chamber and back into the labyrinthine tunnels.

“So that wasn’t scary at all,” I said, sliding the razor sharp blade into its sheath, noting in passing the other side of the bade, which read, ‘eiice me.’

“You did well,” Nimue said approvingly.

“What if I’d done anything differently?”

“Ah, but you didn’t. Kilgharrah still sleeps and the sword is yours.”

“So, it was a test?”

“Do you believe the sword of Albion’s true king should be passed into the hands of just anyone?”

“You could have warned me.”

“I didn’t offer the sword. You asked for it. It was returned to my hand at the end of Arthur’s life and it has remained my responsibility through the centuries since then. Do you think I did wrong?”

That was a tough one. The sort of question a dad asks when you know what the right answer is but don’t want to own up to it.

“Merlin?” I addressed the older wizard.

“This has nothing to do with me.”

“No, we spoke of this. You said you could transform it.”

“Are you sure?”

“I... Yes, I am. If I try walking through Glastonbury with this thing, I’ll be arrested. No-one’s going to believe that a weapon in this condition is over a thousand years old, so no-one will believe it’s Excalibur, regardless of the inscription or the blade design.”

“You recognise it then?”

“Different legends describe it differently, but it kind of makes sense it would be a Roman sword. Not a gladius. It’s too long for that.”

“A spatha. And the inscription? Suscipe me?”

“Take me up. And Eiice me means cast me away. Those are also in the legends written about the blade, though most say it would be in Celtic runes.”

“On a Roman sword?”

“Fair point. Which means if anyone were to recreate the sword today, the replica would most likely look like this.

“I can’t use it in modern Britain, and no-one’s going to consider it any sort of proof that I’m Arthur’s heir.

“If I’m to keep it, it will have to take on a new form. Besides, what we discussed is more my style.”

Merlin placed his hand upon the blade and muttered a few words in what sounded like Welsh. The sword glowed and shrank until what I held in my hand was a fountain pen.

Nimue’s eyebrows shot up. “We came all this way for Arthur’s sword only to do this to it?”

“Of course,” I said. “Haven’t you heard, the pen is mightier than the sword?”

“But...”

“Why did you test me just now? Was it to have me prove to you that I deserved the sword, or was it your way of showing me that I am rightful queen of Albion?”

“Perhaps as much one as the other.”

“So now we both have what we need of it. There isn’t a man or woman alive who would believe my claim simply because I held Arthur’s weapon, and if there is magic to be had in its wielding, then my battles will be won and lost according to the words written on pieces of paper. This is a warfare I can understand.

“Merlin, would you agree she has proven herself.”

“With some reluctance, yes.”

“Then Lady Nimue, I am Queen Gwendolyn of Albion, and I would welcome any help you might give me, if you are still willing.”

“What is mine to give, I give you freely.”

How can you describe a spiritual wind? When I had accepted Merlin’s help, Lance had been there and I had been distracted by him and missed the old man’s gift. Here there was no distraction, so I felt the full effect as a gentle warmth blowing into me and through me, filling every part of me and leaving my skin tingling.

I slid the bag from my back and found a secure place for the pen, then I touched my watch which flare bright in the darkness.

“Shit. Half an hour. I’m never going to get back in time.”

“You might,” Nimue said. “Let your instincts guide you.”

I didn’t need her to tell me anything more. I could feel a gentle tug inside me and followed it, increasing my pace at each turn.

Quite what that instinct was I doubt I’ll be able to define. Perhaps I simply had some subconscious memory of the turns we had taken coming, perhaps there was something more mysterious at work. I don’t know, just that the journey out took half the time of the journey in.

Back in the sunlight, I was ready to run for the abbey, except a sense inside guided me back to the ghostly inscription that had opened the way. The words were the same, so I spoke them once more and felt the ground close up.

What had Nimue gifted me with? I had no way of finding out in that moment but put on a burst of speed. Somehow my way back to the abbey was less restricted by the Brownian motion of tourists and I made my last sprint up the hill and into the ruins just as two o’clock chimed from a nearby clock tower.

“You’re cutting it fine Miss Llewellyn. Was your visit worth the effort?”

“I think so sir, thanks for allowing it.”

“Did you find any interesting inscriptions?”

“Er, hic iacet sepultus inclitus Rex Arturius in insula Avalonia?”

“A fair recitation. Where did you see it?”

On the side of a hill in ghostly blue words only I could see. Invitation to a padded cell, perhaps.

“In a souvenir shop. It’s one of the inscriptions you mentioned as possibly being on Arthur’s grave.”

“Was it also in this souvenir shop that you managed to get so grubby?”

“No sir. I, er, I kind of fell over hurrying to get back on time.”

“Hmm. Well, can’t be helped. In future, remember you represent the school every time you leave the grounds wearing that uniform.”

“Yes sir, sorry sir.”

“No matter. Alright everyone. This afternoon I have a rare treat for you. I’ve secured access for you to some of the illuminated texts that survived the abbey’s destruction. The documents are immensely old and need to be treated with the utmost respect. I will expect you to be on your best behaviour.”

It proved to be far more interesting than anticipated because, without apparent rhyme or reason, I found myself so much more able to read and translate the illuminated texts on display. That wasn’t part of the exercise though and I kept silent until the end of the tour when we were shown the damaged final pages of the manuscript in process of being copied out. The current page had a large piece missing with a best guess for the missing words written in.

I held up my hand and pointed at the recreated text, suggesting an alternative. “The grammar is wrong, of course, but it’s in keeping with the rest of the document, and the lettering fits in with the partial letters you can still see.”

That earned me a few looks suggesting the padded cell might still be an option, but the institute owner who’d been showing us around printed out a copy of the current page complete with missing piece and asked me to show him, so I took a pen and managed a fair continuation of the text, matching letter size and spacing to the original and fitting the words I’d found to the fragments at the torn edges.

“That’s astonishing,” he said. “I believe you’re entirely right my dear. It changes the context of our translation completely. Patrick, I don’t suppose you’d consider lending us this young lady for a week or two?”

“Er,” Mr Phillips looked at me as though I genuinely had grown a second head, one unaccountably able to handle Latin texts better than he could. “Er...”

“I’m afraid I have other studies in need of my attention, sir,” I said.

“Yes, of course. If there’s any time you can spare us though. We’d pay you, obviously.”

I left them with a vague promise that I’d talk to my parents.

On the drive home Mr Phillips invited me to sit up front next to him whereupon he interrogated me over the matter.

“I really don’t know sir,” I said. “It just sort of clicked. The other pages we read on our way through had the same sort of sentence structure to them.”

He questioned me at length, and I was able to quote sections from other pages we’d seen. Most of the class had drifted through the afternoon in a sort of glassy eyed numbness. The only reason I hadn’t joined them was this newfound ability of mine. The subject material had been an account of a little-known knight in his search for redemption, the story somewhat mundane, but what had captured my attention was the ease with which I could read it and the offhand way in which I picked up the author’s common and repeated errors in conjugation.

Mr Phillips and the Latin Inquisition gave up after about an hour which left me a half hour’s peace.

This is you, Nimue, isn’t it? I focused on the thought.

“Of course,” she said from the empty seat beside me. At least it had been empty until she appeared there. Her sudden arrival gave me a start, which in turn earned me a suspicious look from Mr Phillips.

You’re going to have to work on making your appearances a little less abrupt, I thought. Merlin usually appears somewhere behind me at a safe distance and speaks gently.

“And where’s the fun in that?”

No fun perhaps, but at least I’m less likely to be thought insane.

“I’ll try.”

How?

“The Latin? You can’t expect me to have lived through centuries and not learned some small amount. Latin was the language of scholars in my time and its mastery a requirement of any learning, and now we are joined, all that I know is there for you to draw on.

What else is there?

“That will become apparent in time. The history of this land for one. What you merely read about, I experienced, at least in some manner.”

Magic?

“Of course, though be cautious in using it. Learn from my first mistakes.”

Is that why Merlin hasn’t shared his own thoughts?

“I cannot speak for Merlin, though I suspect so. He has a mastery of more subtle magics of the sort I have little patience to learn, so it is quite possible he can mask his thoughts from you. Perhaps with good reason. I was always the wild one and, though I have mellowed with the passing years, I don’t coddle as he does.”

“I do not coddle,” Merlin said from a few seats back.

Okay, stop! I massaged my temples which were beginning to throb. Let’s get one thing straight. My mind is not a field of battle for you two to work out your differences.

“Yes, you highness,” Merlin said, instantly contrite.

“Yes, of course,” Nimue added. “I’m sorry.” Less respectful but just as sincere.

Merlin, is it through a desire for privacy that you keep your thoughts from me or concern over what harm I might come to?

“A little of both, majesty.”

And some of your concerns of permitting Nimue to join with me that I might have access to powers I’m not ready to wield.

He didn’t respond.

“I wonder if he ever thought to teach you his magic.”

“It does concern me, Gwen, for I have seen too often how power corrupts.”

“Not always, my lover. We two did not become monsters for possessing these magics.”

“I have often enough regretted my use of it. Consequences are not often immediate, but there are always consequences. To use magic without first understanding all that might come of it is reckless.”

“And to withhold magic until you know all is to cut through your own hamstrings.”

Then perhaps there is a balance between the two which will work, even though it may not be perfect. I will need both your counsell to achieve this balance.

But let it be counsel only. You will not argue in my presence but present me with your thoughts. Allow me the choice and the burden of any consequence.

“Yes, your majesty,” they both replied.

Now if you wouldn’t mind, I’d like a little peace before we return to Marlborough.

The rest of the journey passed in silence. Mr Phillips gave me a look as I climbed down from the minibus. I smiled at him, but I could tell it wasn’t over.

I was still grubby, which was probably what bothered Mr P, so headed for my dorm to change.

“Merlin,” I said quietly.

He faded into existence beside me.

“Will you teach me a little about magic?”

“What is it you wish to learn?”

“If I wanted to clean the dirt from my clothing...”

“Then all you would need do is loosen the bonds that bind the filth to the fabric,” Nimue also appeared unbidden.

“It is true that would achieve your end, but in loosening the bonds of one thing, so you would loosen the bonds of another. The fibres would cling to one another with less strength, the material would weaken, the dyes would fade away...”

“Unless you also strengthened their bonds after...”

“And in so doing you would have to draw strength from something else. The fabric of the world. Like is to like, so most likely you would weaken the fibres in some nearby plants, which would likely wilt and die.”

“Sure, but who cares about a few plants?”

“If they were weeds, I would find it hard to care much,” I said.

“Although weeds have their place in all that connects life. Butterflies often require nettles and the like to live. Dandelions, clover, henbit and dead nettle, all are beneficial to bees. All the variety of life is interwoven, and to destroy one part is to risk damaging another.”

“Consequences.”

“As you say.”

“I think I’ll just put it in the wash.”

“A wise choice.”

“My thanks to you for your input though, Nimue. It makes little sense to risk untold harm when there is a more mundane manner of seeing a task done.”

“You’re as bad as him,” she snorted and vanished.

“And what do you say to that?” he asked.

“Perhaps I am. What consequences were there from the transformation of Excalibur?”

“Now that is a challenging question. It will have lost none of the strength of its magic, though what nature that magic will take remains to be seen.”

“What do you mean?”

“As a sword, it was both hard and sharp enough to cut through iron, so rendered its wielder able to both disarm an opponent and cut through his defences. The scabbard also possessed an enchantment, to prevent whoever held it from bleeding. As a pen, and I presume its lid, it should grant you powers of similar strength, though what form they will take I cannot predict.

“Changing it from a four-foot steel blade into a seven inch pen of sterling silver, there is another matter. Where the steel went, I cannot say, though of a certainty it would have gone where it was most needed. Where the silver and copper came from that formed the alloy, this also is a mystery, though both silver and copper were once mined in the region, so there is a high likelihood it was naturally found and not taken from some nearby jewellery. In transforming from the greater to the lesser, the materials would not diminish the world but rather enhance it.”

“Is that what you believe, that I have diminished Excalibur?”

“It is a manner of speaking. Whether the sword has truly become something less than it was remains to be seen, but five pounds of steel reduced to fifteen grams of silver, in this manner it was diminished.

“May I look upon it?”

I took it out of my bag and held it up where we could both see it.

“Yes, the inscription remains, do you see?”

Finely etched in the grain of the silver on the pen's barrel, I could just make out the Latin inscriptions.

“Arthur carried the sword with him every day and used it whenever he was called upon to fight. Might I suggest that you do likewise?”

“Just write with it, no matter what?”

“Perhaps allow it to lead you, but I see no reason why not. Also, wear it where others might see it. The sight of Excalibur spoke to those who met Arthur.

“Now, here is your chamber and I hear others within. Perhaps we should continue this conversation another time.”

Marie, Abbey and Elaine were changing when I entered. Elaine was the first to react.

“O-M-G. Whatever happened to you?”

“Long story and I’d rather take a shower than stand here recounting it if you don’t mind?”

I stripped off my uniform and underwear, slipped on a dressing gown and headed for the shower.

Fifteen minutes later, with my hair lathered clean and my skin tingling, I returned to the room to find the three of them examining Excalibur.

“Where did you find this?” Marie wanted to know. “It’s beautiful.”

“I took it from the stone grasp of a statue lying between the forelegs of the largest dragon you ever saw,” I said.

“Fine! Don’t tell us. Cow” She threw it at me, and I caught it easily enough.

“I’ve been looking for something to use to try writing old school for a while now. Mr Ambrose says there’s nothing helps you feel the words like putting them on paper with a proper pen. When I saw this, I just had to have it.”

“So why didn’t you say that in the first place?”

“I didn’t expect you to be so upset about it. It’s sterling silver, so should be pretty tough, but I’d appreciate you not throwing it about though. You know, in case it gets dented.”

“Yeah, okay. Sorry. It really is pretty. Did it cost much?”

“It is quite valuable, yes. It’s vintage, from before when hallmarks were required.” Probably before when they were first used for that matter, but we’ve already seen how they cope with the truth.

“Do you know if it’s real silver?” Abbey asked.

“I’m less worried about the material than knowing how old it is, and I’m pretty certain about that.”

“Have you tried writing with it yet?” Marie interjected.

“No. I don’t have any ink.”

“Bring it here,” she sighed, pulling a squat little bottle from her desk drawer.

There was a little lever in the side of the pen barrel. Marie pulled it out more or less at right angles to the pen, then she placed the nib – gold if I was any judge, as was the sword shaped pen clip on the lid, which meant that someone’s jewellery had been depleted – into the ink and pressed the lever home. She repeated the action a couple of times then dabbed the nib with some tissue before passing it to me.

“Try it. See how it feels.”

It felt very much at home in my hand, as though it had been made for it. I dug out a notebook from somewhere and wrote ‘Excalibur’. Not original, I’ll admit, but somehow appropriate for the first word written by the pen.

Peter had been right; there was something sensual about writing by hand. Whether it was the magic or the fit of the pen, or simply me being a girl now, but my writing was so much neater than it had been.

“Wow,” I said. “So how long should it last on one fill?”

“Depends on a lot of things. Thickness of the nib, the pressure you use when writing, size of the reservoir, obviously. At a guess you’ll get maybe fifty pages out a one fill. Here.” She threw me the pot of ink, lid securely screwed in place.

I caught it. “Are you sure?”

“Yeah. I prefer a rollerball anyway. Fountain pens are so much hard work. If you don’t use them regularly, the ink dries up and they need cleaning. I doubt it’ll be a problem the amount you write. In fact, your problem’s going to be running out of ink. I bet you’ll be looking for a new bottle by the end of the week.”

“I’m guessing there’s somewhere in Marlborough that sells this stuff.”

“T G Jones will be able to sort you out. On the high street.”

“Thanks.”

“How old did you say it was, that pen?”

“I don’t know, just predates hallmarks.”

“Well, the first hallmark dates back to about thirteen hundred, so I doubt it’s that old,” Abbey said.

“It’s not,” Marie chipped in. “That method for filling the pen was invented in the early twentieth century.”

“Oh, okay. I guess that still works. Hallmarks only became compulsory in the nineteen seventies. Nineteen seventy-three, I think.” Abbey again. Fount of all knowledge when it came to jewellery.

“So that dates it between nineteen eleven and nineteen seventy-three. Does that sound about right”

I shrugged. Merlin had offered to make a gun of Excalibur, so it shouldn’t have surprised me that the technology was so up to date. I was glad of it though. I’m not sure how much use I’d have been inclined to make of it if I’d needed to dip the nib in an inkwell every other word.

One word on its own felt insufficient. I returned the nib to the page and continue to write.

‘...is yours to wield. A sword no longer it yet cleaves. Truth from lies and true intent from deceit. The pen's sheath will defend you from lies aimed at you.’

Well, that was new. None of those words had come from me, except maybe the first. Time to try again.

‘Merlin’ I began and continued unbidden, ‘lives no more, yet persists in spirit form. His one ambition is now, as it has ever been, to see Albion ruled by a fair and just hand. He remains cautious to a fault. Having been oft bitten in the past he remains shy of risk. Though his counsel remains of value, it is not reason enough in itself to shy away from boldness.’

And once more. ‘Nimue, is as reckless as Merlin is cautious. She also is of honourable intent, though her disregard for consequence is like to lead into unintended difficulty.’

This was heady stuff. I could write the name of anyone I knew and gain insight into their minds. Power to be abused. To write the name of one of my friends would be a betrayal of trust, I knew, and whatever I wrote afterwards would change how I would see them permanently. Either I would find reason not to trust them or be overwhelmed with guilt at not having done so.

There were a few people though.

‘Patrick Phillips.’ I’d learnt his first name just that afternoon. ‘...is a scholar above all else. His great passions are learning and teaching. Though he possesses little enough imagination, he has reason enough to suspect something changed with you today and his intent is to test you at your next encounter. There is little enough reason to hide your newfound capacity for language as he will convince himself of some mundane cause for your improvement, regardless of the evidence he finds. He will stretch even your present capacity and prepare you well for your future.’

And one last.

‘Quentin Girling...’

If you liked this post, you can leave a comment and/or a kudos!

Click the Thumbs Up! button below to leave the author a kudos:

And please, remember to comment, too! Thanks.

Comments

Oh the power of the new Excalibur..

I worry that Gwen might find it to be less than honest, but that is from a childhood reading cautionary tales of magic and misunderstanding.

A really really interesting twist to this story. I hope that Excalibur helps Gwen deal with the odious Quentin Girling, but I fear that what it tells her might in some way be a trick or at least a test.

Lucy xx

"Lately it occurs to me..

what a long strange trip its been."

Trusting Excalibur

I get what you're saying, and there has been a lot about the consequences of abusing magic in this tale, but Excalibur never let Arthur down in the legends. The only reason Mordred was able to deal him the killing blow, was because he dropped Excalibur and its scabbard at the Battle of Camlann before Mordred struck him.

Excalibur is pretty solid and it has a noble purpose, so not likely to cause mischief.

Dragon names

For those who read this early, I realised where I got the White Dragon's name from. Wrong legend, wrong fantasy world. So I changed it. Kilgharrah at least comes from an Arthurian version of things (even if one with more artistic license than pedigree)

‘Quentin Girling...’

My mind jumped straight to that name when Gwen discovered the pen's ability. I can't wait to see what Excalibur has to say about him.

Hugs

Patricia

Happiness is being all dressed up and HAVING some place to go.

Semper in femineo gerunt

Ich bin ein femininer Mann

You Are A Witch

This chapter wove belief and hilarity into a single skein. The interplay between not only Merlin and Nimue but also our Queen was amazing, Gwen handled them both and basically has them eating out of her hand!

Mr Cavendish was also amazing. He disarmed the press and Lance's parents with a single blow. We must assume that Lance will step up to the plate (or the wicket) and prove his scholastic worth by Christmas, thus further neutering his father.

And I love that "the pen is mightier than the sword" schtick. Could it possibly be an autopen? It will certainly be a mighty weapon for Gwen if it gives her insight into both her friends and enemies, as long as she uses it wisely.

I'm very much afraid you have created a heroine for the ages.

That's true magic!

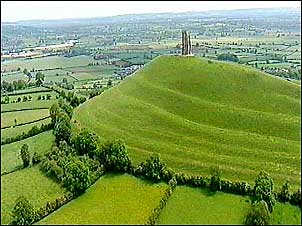

And I assume that is the mound at Glastonbury. I've not been there, but it's plain to see how much labour and accompanying belief must have gone into its creation. A fit place for the burial of a dragon and King Arthur.

Glastonbury Tor

Is actually a natural feature, so geologists tell us. It's formed from tougher rock than its surroundings so has been naturally weathered. Silbury Hill (Nimue's resting place in this tale) is officially the biggest man made mound in Europe, however Glastonbury Tor is too neat of a shape for me to leave it like that, and it was (I believe) an island back when the low country around it was flooded, so meets all my criteria for being the Isle of Avalon (it would have been out in the middle of lake Avalon, now the Avalon Marshes but formerly Nimue's 'Lady of the Lake' lake). There are those who would say that Avalon is out somewhere in the Irish Sea, but not in this story.

Thanks for the witch compliment. I can see me self in black. With a pointy hat and a p... cat.

I Don't Believe It

Glastonbury Tor doesn't look natural to me. I look at the surrounding country and....naah!

When I first started writing Knight in White Satin...

before it became a part of this story, I introduced it with, 'Geologists will tell you...' then went on to speak about their ideas of the natural formation of mountains. I then introduced the reality, that they were the resting places of dragons, now buried after millennia. Volcanoes would be where the restless loners put their heads down and still grumble occasionally in their sleep, and mountain ranges where the gregarious majority all huddle together, so from my perspective, there is no such thing as a natural hill or mountain.

The Hemlock Stone (pictured in my first ever story Way into Wonderland) also doesn't look natural, but for totally different reasons.

I'm glad you agree with me that Glastonbury Tor doesn't look natural because, as you so succinctly put it, 'Naah!'.

Behold!