Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

Permission:

“For some people,” she said, “forgetting is the closest thing we can make to forgiveness.”

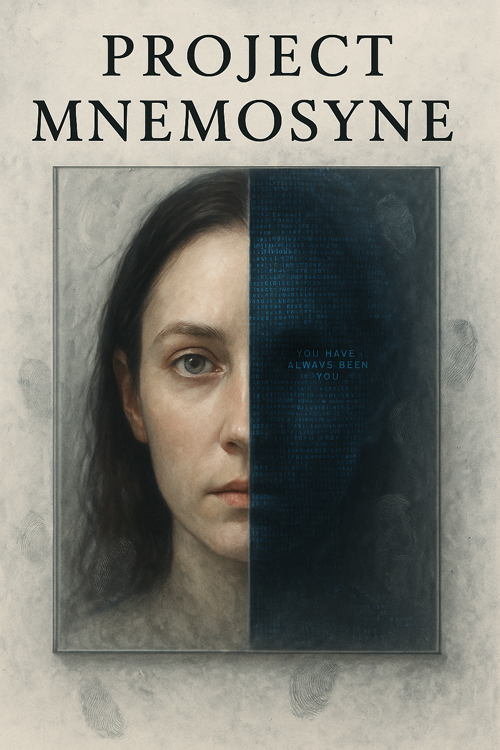

Mnemosyne

Chapter 2 - Alternative

by Suzan Donamas

with Chat-GPT

Chapter 2. — Alternative

Document Header

From: Ministry of Justice, Office of Sentencing Review (Region-7)

To: Warden, Central Remand & Execution Facility; NeurogenZ International (Local Liaison)

Subject: Judicial Order 47-B — Conditional Commutation, Subject: Kral, Anton (ID# R7-36199)

Classification: CONFIDENTIAL – COURT SEAL APPLIED

Order: The scheduled sentence of death for the above-named inmate is deferred upon the inmate’s enrollment in Experimental Therapeutic Program MN-9 (“Mnemosyne”) administered by NeurogenZ International, under supervision of the Ministry of Justice. Inmate will submit to all procedures deemed necessary by attending medical personnel. Failure to complete program, withdrawal of cooperation, or adverse clinical outcome shall reinstate original sentence without further hearing.

Consent: Per Statute 22.4(c), consent is satisfied by signature or mark acknowledging comprehension of commutation terms read aloud in presence of a Ministry officer.

Effective: Upon transfer of custody (timestamp appended).

Signed: Chief Magistrate B. Miros, Region-7

Countersigned: Capt. L. Varga, MoJ Liaison to NeurogenZ

—

They woke him the way guards wake a man they are done with: not gentle, not cruel, just finished. Anton learned the difference years ago. Finished meant they called your name like they were closing a file and waited by the door with eyes that kept walking even when they stood still.

“Kral,” the first one said, so he’d answer to it in case he’d learned another name in his sleep. “On your feet.”

He’d slept badly in the cold that smelled of disinfectant and bodies that had learned to be quiet. He swung his legs off the bunk, every scar remembering its own reason for being there. The cuffs were already in the guard’s hand, the chain between them speaking a small metal word as it moved: now.

They walked him through a corridor he didn’t know well because he’d only been on it once before, wrists together, knuckles grazed by the ring of steel when he swung too far to keep pace. The fluorescent lights hummed the way electric insects might hum if they were sick. He counted the lamps to keep the old habits busy—eight, then a gap, then five, then the dark patch where damp had and would always win—until the counting could become another thing to hold.

A metal table waited in a narrow room with a window that didn’t look out; it looked in, from the other side. On the table lay paper he could not read and a pen he could hold. The Ministry crest stamped in blue sat at the top like an eye you couldn’t close.

Captain Varga was there in a uniform that believed itself, hands easy on his belt. “Mr. Kral,” he said. Not Subject, not Condemned. Mister like they were being polite at each other’s funeral. “We have an opportunity for you today.”

The guard clicked the cuffs to the loop bolted under the table. The metal cooled his skin. Varga sat opposite. A second guard positioned himself near the door; a third stood where Anton could feel him but not see him, like a habit in a room.

Varga tapped the papers. “Judicial Order Forty-Seven B. Deferred sentence, conditional commutation. It means the rope stops if you agree to a medical program.”

The word rope put a dry taste in Anton’s mouth, old rope and dust and sweat and the time his grandfather used one to tie a calf that had already decided to die. “What program?”

“It’s for rehabilitation,” Varga said, and Anton heard that word like a hand smoothing the nap of his hair the wrong way. “They give you something to help you become a person who won’t do what you did. You complete it, you live. You refuse, we reinstate the schedule. Understand?”

There was no malice in it. That was worse. Malice meant you could fight a person. This was a hallway with a slope.

“I want a lawyer,” Anton said, because some words were always allowed to make shapes in your mouth even if they never made a difference.

“You had one,” Varga said, and it was true somewhere else. “This is administrative, not adversarial. Consent is read aloud. You make a mark. The mark stops the clock.”

Varga read. The order’s language crawled along the table and tried to climb into Anton’s head by way of the captain’s voice, which was trained not to get tired. Deferred. Enrollment. Cooperation. Adverse clinical outcome. Reinstate. The words had corners. They scraped on the way in.

“What’s the… drug?” Anton asked. He’d heard stories that sounded like movies until they had real walls.

“It’s an infusion,” Varga said. “It helps the doctors change things.”

“What things?”

Varga looked sideways as if the question had to pass through a checkpoint. “How you see yourself,” he said. “And because of that, how you act. The brain can be trained, but this is faster. Cleaner.”

Anton watched the man’s jaw move and thought of the two kinds of lies in the world. The first was the kind you told to get a result. The second was the kind you spoke because you had already accepted it until your mouth had to agree or your head would split. This sounded like the second kind.

“If I say no,” Anton said.

Varga took a pen from the table and turned it in his fingers like a coin trick. “Then we continue with what the court ordered,” he said. “Tonight, tomorrow, the day after. Depends on paperwork and the calendar.”

“And if I say yes and then, later, I say no?”

“Then you said no,” Varga said. “There’s only one yes.”

On the far side of the window that was not a window, a shape moved and became a person and stopped where the light had not been told to go. Anton felt eyes find him without a face, felt a thought press against his skin and withdraw, like someone testing glass with a knuckle.

“Read it again,” he said, because asking to hear a thing twice was a way to make time move slower in rooms where time was oil.

Varga read it again. The guard by the door shifted his weight like a curtained breeze. The ink on the page looked wet even after it dried. When Varga finished, he slid the pen across as if it were evidence.

Anton took it because everyone did when a pen wanted their hand. He could write his name. Saying I can’t read had been a test. He watched the captain not flinch. Good. Facts that didn’t move were better.

He made a mark that wasn’t a letter but could have been the promise of one. A crooked slope. A hill to climb or tumble down. The guard unlocked the table ring with a click that said: now, not later.

They walked him another way—through doors that opened at someone else’s permission and closed like rules. They took his shoes someplace and gave him others, softer, which made his feet feel like they were sneaking without him. The corridor bent twice, then tunneled under a sign that didn’t bother with words. The air was cooler. The light learned to stop at the line between tile and glass.

In the prep room, the chair waited with straps arranged like polite hands. A woman stood beside it. She wore a badge and a face a person had practiced to use on people who had reasons not to trust faces.

“Mr. Kral,” she said. “I’m Dr. Ilyanovsky.”

He looked at the badge because men looked at badges in rooms like this. D.M. Ilyanovsky. He filed the initials in the part of his head that held on to names because names could sometimes move closed doors.

There were others—coats white enough to glow, a man whose coat wasn’t but whose smile was, two techs who had learned to step without sound. The one with the smile wasn’t smiling as much as his mouth remembered how.

“You’ll sit there,” the doctor said, and he did, because he’d learned there were fights that were only shape and fights that were air, and shapes won.

The straps went over his wrists with a small politeness that felt like an insult to other kinds of tying. The leather was the wrong temperature. He tested the range of his shoulders and got half a shrug for his trouble.

“Have you eaten, Mr. Kral?” the smiling man asked, like this was a clinic and this was about ulcers.

“No.”

“Good,” the man said. “Piers Gornik,” and he tapped his chest with two fingers in a way that suggested he didn’t expect Anton to care but wanted the room to hear the sound of his name.

Dr. Ilyanovsky’s hands were neat, workman’s hands on slender wrists. She checked his pupils with a penlight that wrote brightness on the backs of his eyes. “Any allergies?”

“No.”

“Any surgeries?”

“Stab wound,” he said. “Twice. They didn’t call it surgery, but there were stitches.”

Her mouth made a movement it didn’t finish. “Understood.”

He watched her not look at the glass wall. He followed her gaze to the rack of bags climbing on a pole, clear fluid like something rain had left behind after it learned to be clean. The tube that would be attached to him hung with the patience of snakes that remember what they are for.

“What is it?” he asked, because his mind made a shape like it was already using the word drug, and he wanted to pin it to something with letters.

“It lowers certain kinds of noise,” Dr. Ilyanovsky said. “And then it helps us write a different kind of signal. You’ll feel warm. You might feel… undecided for a while. We’ll talk you through it.”

“I don’t like people talking me through things,” he said, and that was truer than most of the sentences he spoke to people in rooms with chairs.

She nodded once, as if the sentence had tamed something. “Then we’ll talk when you want.”

“What happens if I don’t wake up?” He meant the question like a joke and it came out like a voice that had forgotten how to laugh.

“Then the Ministry reinstates your sentence,” Gornik said, cheerful as weather. “Same outcome, different route.”

“Piers,” the doctor said without volume.

He looked at her, then at Anton, and put his hands in his pockets like a schoolboy who had broken a rule and found it tasted fine.

A tech swabbed the crook of Anton’s arm with something that smelled like the way hospitals make their apologies. The needle slid in with more confidence than pain. The machine that would move the fluid from the bag to the vein clicked a sound that wanted to be counted. He let himself count it to keep his breath company.

Through the glass, shadow moved and became Captain Varga, then something less human—one of those ceiling eyes that watched everything in case it ever tried to become something else. Anton kept his gaze on the doctor’s face because faces were a skill of his. Men who had learned to take what they wanted learned people by the way they made space in their mouths before they made words. He listened to the air between her teeth and her tongue and decided she would tell the truth until the truth became a door that wouldn’t open.

The first bag began to empty, not fast, not slow. Warmth walked up his arm and made itself at home behind his collarbones. His mouth remembered a thirst and then forgot it. The edges of the room softened the way walls did when you looked at them through water.

“Okay,” he said, to no one in particular. It surprised him that the word was polite without meaning it.

“You’re doing well,” she said, and he wanted to ask what well was for men like him but the question decided to find a chair and rest.

The machine clicked, a metronome keeping time for a song he didn’t know yet. He watched the clear liquid—nothing always looks like nothing until it doesn’t—climb down the tube in beads that learned to be a line. His fingers twitched once the way dogs’ paws do when they chase something asleep. The strap reminded them what was allowed.

“What happens after?” he asked, and he didn’t know if he meant tonight or mornings or whatever the word after meant when you had already watched the clock fold its hands up.

“After which?” Dr. Ilyanovsky asked. Her voice was the sound of hands being washed properly.

“After I wake up with your signal instead of my noise.”

“We see if your new memories hold when the room changes,” she said. “We see if you want what you remember wanting.”

The warmth became something like a hand making circles between his ribs. He had a memory of a woman doing that to a dog to keep it from shaking in a storm. He knew he’d never seen it. He felt it anyway.

“I don’t want what I wanted,” he said, and the sentence fell out of his mouth like a drawer you hadn’t meant to pull. He didn’t know if it was true and that was the point.

“That will help,” she said.

“You sure?” He tried to find the grin again. It had wandered off somewhere he couldn’t reach. “What if you make it too good and I forget everything?”

Her eyes flicked to the glass then back. “For some people,” she said, “forgetting is the closest thing we can make to forgiveness.”

He let that sit in his head and it found a chair immediately, like it had been there before and kept a coat on the back. The edges of the room leaned in, friendly-like.

“You tried this before,” he said. “On a man who got quiet and didn’t come back.”

The techs found instruments to look at that weren’t him. Gornik coughed into the inside of his smile. Varga didn’t move, or moved exactly as much as the role allowed.

“Yes,” Dr. Ilyanovsky said.

“Did he deserve it?”

There was a longer pause than the room thought it wanted. “Deserve?” she said finally, and the word was so clean you could see the ceiling lights reflected in it. “He was a patient. We failed him.”

Anton looked at the ceiling because ceilings were honest. They had no reason to be anything else. The click of the pump had already taught his heart to keep a similar beat. “What if I don’t fail you,” he said, and he heard how the sentence lined up with the kind of man he hadn’t been. “What if I do what you want and wake up wanting the right things?”

Gornik brightened. “Then, Mr. Kral, you will be a very important man.”

“I thought I was going to be someone else,” Anton said, and then he laughed, and then he didn’t.

Dr. Ilyanovsky adjusted the rate on the pump, not much, like moving a story forward one page because you couldn’t sleep otherwise. “Close your eyes when you like,” she said. “You’ll hear my voice sometimes. You can ignore it.”

“I always ignore voices,” he said. “That’s why I’m here.”

He let his eyelids think about it. They surprised him by agreeing. The room dimmed with the kind of mercy fluorescent lights don’t have. He heard the machine’s arithmetic and the whisper of something settling under his skin. He felt the straps remember him. He saw a hallway he had never walked down—blue tiles, sunlight in squares, a smell of oranges and chalk. He heard shoes he had never worn squeak. A child’s voice called Anya very softly from the doorway, like a secret and a dare.

“Not me,” he said, but he didn’t say it out loud or if he did the room chose not to answer.

Somewhere behind the glass, someone wrote something down. He heard the sound the way a man hears rain learning the roof.

“Mr. Kral?” Dr. Ilyanovsky said, but it wasn’t her. It was a woman whose hands smelled like sugar and soap and cigarettes held between two fingers she didn’t want to stain. He knew the smell; he’d never met the woman. He tried to stand up to see her and the straps reminded him about promises.

“Anton,” another voice said, not hers, a deep voice with a chipped tooth in it. A voice he knew. His own. “Stay.”

He stayed. He didn’t have a choice but even when he did, he had. The chair meant he could blame something with legs.

He dreamed he was holding a doll and the doll was a heart and the heart was a room that had a door he could open by saying a name he had never been called. Anya, he said, and the door practiced being a door.

“Vitals stable,” someone said.

“Consolidation window?” someone else asked.

“Six minutes,” Gornik said, maybe, or the voice that lived in his coat said it for him. “Begin scaffold echo.”

A whisper began. It wasn’t a voice. It was the shape voices make before words. It moved along the inside of his skull like a finger on frosted glass, writing letters that were pictures of letters, tracing a spiral he’d seen once in a church on a ceiling he’d laid on a bench to look at, except he hadn’t, except he could smell the beeswax in the wood.

“Anya,” the woman whispered gently from a far room sunlight had learned to visit. “You’re safe.”

“Not me,” he thought again, and the thought landed like a bird on a wire already full of birds that made room because they’d been him once and were still.

The warmth became a shore. Something soft knocked at his bones. The pump kept time for a song that had begun long before he’d learned to listen. He opened his mouth to ask for water and a child answered for him from a kitchen he hadn’t stood in, handing him a glass he couldn’t hold because his fingers were smaller than they were supposed to be.

“Good,” Dr. Ilyanovsky said, far away. “Good.”

He floated in the part of sleep where rooms forget to keep their corners. The straps became stories. The ceiling forgot it was a lid. He heard his name spoken like a memory could pet a man. He heard another name spoken like a memory could grow one.

When the first bag emptied, the room did not clap. It exhaled through the ducts and recalculated.

Anton opened his eyes a crack because some men learn to sleep with their eyes half open the way dogs do when they pretend to trust you. Through the narrowest slice of world he saw the doctor looking at him the way a person looks at a photograph when they think they’ve seen the stranger in it blink.

“Doctor,” he said, or thought he did, or someone did with his mouth. “If this works…”

“Yes?”

“Will you remember me?”

She didn’t answer. The pump did, and its answer was yes, no, yes, no, yes, no in green on a screen.

He let his eyes close all the way. He watched the hallway with the blue tiles become a beach with no footprints yet. He watched a small girl pick up a shell that had learned to be an ear, hold it to her head, and listen to herself coming back from the other side of whatever you call the thing that waits.

He hated her a little for how gentle she was. He loved her for how much she did not know she could be broken. He slept, because someone had asked him to in a voice that expected to be obeyed and because the straps were not arguments, they were agreements.

Outside the glass, Captain Varga checked his watch like time worked for him. Dr. Gornik wrote a number and drew a circle around it and smiled because circles are completions even when they are traps. Dr. Ilyanovsky did not move for the length of a breath that a clock would call three seconds and a body would call a door.

“Start consolidation,” she said, and the machine began to tell a story it already believed.

If you liked this post, you can leave a comment and/or a kudos!

Click the Thumbs Up! button below to leave the author a kudos:

And please, remember to comment, too! Thanks.

Comments

Another...

Well fitting chapter to compliment the first. Felt like the first 1/5th was a repeat of some of the first, so I'm going to reread the first and then the beginning of this one to see where I got lost or whether I get the differences between the two.

A lot of what I read though stylistically is continued from the first chapter, and is very pleasing, visually so, sets a certain mood, and has absolutely drawn me in. Trouble I have - and this is NOT a knock because you're integral to the production of this w/ the AI assist - I want to believe you wrote every word, that you set the mood, the direction - which of course you did, but its feels so clean and perfect and sometimes verbose as if a chorus of authors fought to create it, but in a good way.

Super intriguing and I'm trying to suppose the story you're crafting and if it is as I hope - then wow, very cool and well done, spooky good... I'm sure that's a bunch of confusion in this comment and I'm not even sure if the ceiling is doing it's one job, but I feel a bit hooked up to that blasted machine, and this work of yours is sure looking to be a brilliantly crafted story! Thanks for sharing and wrangling the AI component to your whims and wants. Please keep it coming!

Hugz!

Rachel M. Moore

Repetition

The repetition is kinda sorta deliberate. What happened is the first chapter is told from Maya's pov with her as the central character. Chapter two, as directed by me, is told from Anton's pov, and I said to retell some of the same parts from the new pov. Which also introduced a sort of continuity error, which I chose to leave in.

In chapter 1, Maya is reading the consent form to Anton, and in chapter 2, Captain Whosis is reading it. In both versions, Anton makes a mark of consent. Since this is a story about how memory works, I left the discrepancy in. Anton's memory is already corrupted, or perhaps reality is.

I liked the effect, so I left it in. It gives me a good excuse if I miss correcting other continuity errors. Heh.

Thanks for commenting, and so quickly!

Suzan

I like hearing...

Your insights and the purpose behind what you've done - the shift of perspective - why keep the repetitive - is there a matrix or not. (lol) Yeah, big slap on the forehead on the Doc vs. Anton perspectives I missed. You'd think I can't pay attention! Well done work thus far though and I'm excited to see how you unfold it for us. I imagine there will be some surprises we might not expect - the corrupt mind as it reconciles reality or maybe the measurement of success ends up being on a sliding scale. Enjoying what you're doing... <3

Hugz!

Rachel M. Moore

I think there will be surprises

This isn't quite like any story about mind control I've ever read. The instructions I gave, the choices chat offered me, turned out different than I had supposed. I had imagined a fairly typical story of feminization with lots of reluctant discovery and dawning realization with a dark edgy feel. This is something different. I could make some comparisons to well-known and obscure science fiction, but at this point, those might be spoilers. Heh.

Suzan

I’m feeling like a smart reader

Since I caught that discontinuity. I figured there was a purpose to it, so it didn’t bother me. :)

I haven’t read a lot of authors who are experimenting with AI, but I have read a couple stories by one other author who uses it. There are some stylistic similaritie, and that makes me wonder whether that’s an AI mark. I’m not getting on my high horse about it; I don’t use AI to write but I do use it for cover art. But I’ve noticed AI art tends to have a somewhat homogenizing effect, and I wonder if the same is true in writing.

Still a gripping story!

— Emma

Pasteurized

Yeah, there may be a homogenizing effect; I have noticed that in AI art. But I'm more troubled by the pasteurization effects; there are storylines chat will not explore. Art can flourish in such environments, but it is harder, and in some cases, it reduces art's scope and relevance. I'm thinking of the Hays Office in films, the Comics Code, and network bureaus of standards and practices in TV.

When I broadly outlined the premise of this story, chat warned me that there were elements and paths it would not be able to follow.

Oh well.

Suzan

That's an unusual writing style.

I'm enjoying the way you portray subjectivity. There is no more certain way to express than to make it sit in a chair in front of you where it can't hide.

Thank you, I shall look forward to seeing more.

Objectively...

...subjectivity is an illusion, and vice versa. Heh.

Glad you are enjoying the story, thanks for commenting.

Suzan

"Will You Remember Me"?

Who is me? What is me?

How would you feel if the "me" that you remembered was about to cease to exist?

This chapter is absolutely spooky and you seem to have melded your mind with your AI. Powerful!

Halloween is coming

Turns out, this is a perfect time to be posting this story. Heh.

Thanks for commenting.

Suzan