Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Elements:

TG Themes:

Permission:

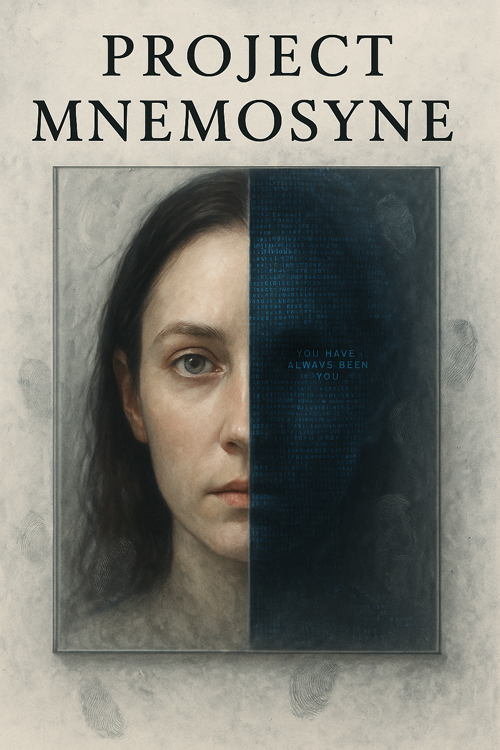

"You are who you have always been."

Project Mnemosyne

Chapter 1 - Parameters

by Suzan Donamas

with Chat-Gpt

Chapter 1 — Parameters

Document Header

From: Dr. Maya Ilyanovsky, Principal Investigator, MN-9 Program

To: NeurogenZ Oversight Board (Remote)

CC: Ministry of Justice Liaison (Capt. Varga), Chief Pharmacologist (Dr. Piers Gornik)

Subject: Phase II Objectives & Demonstration Parameters – Compound MN-9 “Mnemosyne”

Classification: INTERNAL – RESTRICTED – DO NOT DISTRIBUTE

Summary:

Per sponsor directive 2.4.1, Phase II will validate total reconstructive potential of MN-9 through complete personality inversion of a high-severity subject (violent criminal, recidivist). Success metric is defined as (a) stable acceptance of an alternative self-history and (b) behavior consistent with that history under observation and stress conditions for ≥72 hours.

Subject Type: Condemned inmate (male) with documented predatory behavior patterns.

Persona Target: Composite profile (“Anya I.”) designed to represent maximal inversion along axes of aggression–nurture, dominance–empathy, and sex/gender identity; selected to demonstrate scope of MN-9’s reconstructive ability.

Method: Multi-day infusion; guided retrieval suppression; scaffolded memory implant sessions derived from donor baselines; AI-assisted narrative consolidation.

Risks: Identity duality (“ghost effect”); autonomic failure secondary to self-misrecognition; cross-link with donor baseline during consolidation.

Prior Incident: Phase I/07 resulted in psychocognitive null (spontaneous cessation of volitional behavior; brainstem intact). Mitigations detailed in Appendix C.

Ethical Compliance: Waiver granted by Ministry of Justice for rehabilitation demonstration; informed consent substituted by commutation agreement per Judicial Order 47-B.

Investors’ Demonstration: By request, a live observation will be scheduled within 10–14 days of enrollment, contingent on stabilization.

Prepared by: D.M. Ilyanovsky, MD, PhD

Timestamp: 06:12:04 (Local) – Day -1

—

Her cursor blinked at Day -1 until she deleted the dash and typed it back in. It made the day feel temporary, reversible, as if the calendar might decide not to arrive. The monitor cast a rectangle of light across her desk; beyond it, the hall hummed with the high, insect tone of old fluorescents.

Maya saved the memo and let the window collapse to a field of surveillance squares: corridors, intake vestibule, prep, the glass room. A guard drifted through frame chewing gum, hands behind his back like a docent in a museum. The facility had been a military hospital once — tiled corridors, radiators painted the color of toothpaste, a lingering smell of disinfectant braided with damp plaster. On the roof, three satellite dishes faced the same indifferent sky. The feeds stuttered, then settled. Someone somewhere was watching her watch.

She tapped her recorder. “Investigator’s Log, MN-9, Day -1. The sponsor has confirmed attendance for a live demonstration. Parameters accepted as written. Subject delivery scheduled for 08:30 local. I note for the record that Phase I/07 remains unresolved in my mind. The board accepted brainstem survival as nonlethal outcome. I do not.” She let the silence breathe until it felt like a criticism. “End note.”

Dr. Piers Gornik appeared in her doorway without knocking, the hem of his lab coat stained with something the color of tea. “You wrote ‘maximal inversion,’” he said, not quite smiling.

“I wrote what they asked me to write.”

“They didn’t ask,” he said. “They insisted.” He came in anyway, leaving the door ajar as if to prove he wasn’t here. “You saw the Judicial Order.”

“I saw a signature and a stamp,” Maya said. “I didn’t see consent.”

“Consent is a luxury of the uncondemned,” Gornik said. He squinted at her monitor, leaning close enough that she could smell the mint on his breath. “You used your baseline again?”

“For scaffolding, yes.” She kept her voice flat. “It improves consolidation. Less noise.”

“It’s a risk,” he said, too quickly, which meant he’d already accepted it. “Cross-link remains—”

“—a flagged concern,” she finished. “I know.”

He traced an invisible line on her desk with his finger. “It’s a good line, though. ‘Alternative self-history.’” He seemed to like the phrase the way some men liked knives.

“Close the door, Piers.”

He did. The hum of the hall became a softer pressure in the room. He lowered himself into the visitor’s chair and folded his hands. “They want a miracle,” he said. “They want it public.”

“They want obedience,” Maya said. “A miracle is a story you tell afterward.”

“Then tell a good story.” He tapped the folder tucked under his arm. “Dosing plan, per your timings. We’ll go slower on Day 2, a little faster on three and four. Keep him just at the lip.”

“The lip of what?”

He searched for a word and settled for a shrug. “Acceptance.”

Maya took the folder without opening it. In the corner of her screen, the intake camera flickered; a van nosed through the gate, washed pale under the winter sun. She felt her stomach count the seconds to 08:30. The clock disagreed. Time here did not pass. It accumulated.

“Phase I/07,” she said, before she could tell herself not to. “Do you dream about him?”

Gornik stared at the edge of the desk as if the wood grain had answered. “Sometimes,” he said. “He’s very quiet.”

“He stopped choosing,” she said. “That’s not silence. That’s absence.”

“Absence is peace compared to what we do now,” he said. “You prefer the screaming?”

Maya let the folder rest on her lap and pictured the last medical note she’d written in residency: TOD 03:12. There had been a body, a bed, a family with hands. There had been witnesses to the end. What they did here made ends that did not look like endings. Bodies that sat up and watched you and did not know the name you used to call them.

“Investors at ten days,” she said. “Then everything we say becomes evidence.”

“Evidence of success,” Gornik said mildly. “It’s what you wanted once.”

“What I wanted,” she said, “was to stop the part that kills people from being the only part that talks.” Her face surprised her; it had become a smile. “I lost the argument about how.”

He read her smile as assent and stood. “He’ll arrive with an escort only,” he said. “Varga is saving ceremony for later.” He tapped the door with his knuckles on his way out. “Eat something, Maya. You get clinical when you’re hungry.”

When he’d gone, she opened the folder. Dosing charts, familiar as weather maps. The compound designation read MN-9 in black, and under it in ballpoint someone had written Mnemosyne, then scratched out the last three letters until it bled paper. They were always naming things after gods as if that could bribe them.

Her screen bloomed with movement. Men in gray uniforms climbed down from the van and formed a narrow corridor from door to door. Between them, a man in cuffs blinked at the light. He had that condemned look — not the hard jaw from television but the slackness of a body that had decided to stop rehearsing for the future. Under the stubble and the bruised eyelids he might have been anyone.

She could turn away, walk to the prep lab, invent the need to calibrate a pump. Instead she watched, because choosing not to watch was how you let other people decide what you did.

“Investigator’s Log,” she said, tapping the recorder again. “Subject arrival confirmed. Designation: 47. I am noting the absence of the word name in the documentation. I am writing it here for the record: Anton Kral. He is a man. He was a man. I am about to—” She stopped. Wrong verb. “We are about to alter his self-recognition to test a hypothesis about personality plasticity. This is a clinical description of a moral choice made elsewhere. End note.”

She stood and felt the room stand with her. Her hand found her badge, then the lanyard, then the metal warmth of the handle. The hall hit her with its humming and its disinfectant. As she passed the prep lab, two techs fell into her wake without being asked. A third handed her a tablet without looking up. The tablet displayed a consent form with no signature line. Instead, a block of text in legal gray: Commutation Agreement 47-B. Above it, the Ministry’s crest. Below it, a line for her initials acknowledging receipt.

Captain Varga was waiting by the intake door, a coffee in one hand, the other tucked into his belt as if holding up his authority. He nodded once at her badge, once at her face. “Doctor,” he said, as if offering a compromise.

“Captain.”

“Your memo reached the Minister,” he said. “He liked the phrase ‘alternative self-history.’ Very elegant.”

“It was accurate.”

“It was merciful,” Varga said. “Call things what they could be instead of what they are.”

“And what are they?”

“Conditional salvation,” he said simply, and finished his coffee. He dropped the paper cup into a bin without looking and it missed by a little, rolled, and lodged under the radiator. He did not notice. “Let’s begin.”

The door opened from the other side with a reluctance that felt personal. The guards’ faces were all the same shade of watchfulness. The man between them searched the faces arrayed for him and seemed relieved not to find anyone he knew. He did not look at Maya until choice forced him. When he did, it was not hatred. It wasn’t appeal. It was the steady assessment of an animal checking for exits.

“Mr. Kral,” she said, because Subject 47 would make the rest of the sentences too easy to say. “I’m Dr. Ilyanovsky.”

“Doctor,” he said, the word already containing its own apology, and she did not know if he was apologizing to her or to himself for using it.

“You were offered an alternative to your sentence,” she said. “This is that alternative.”

He glanced toward the forms on the tablet as if approaching a heat source. “They told me,” he said.

“You can leave,” Varga put in, bright with the kind of patience that argues with itself. “We’ll resume the standard schedule. It will be tonight or tomorrow, depending on—”

“I’ll do it,” the man said, fast, as if interrupting a litany. His gaze was still on Maya. “I’ll take the thing.”

“The thing,” Gornik repeated, stepping from the wall like an explanatory footnote. “Compound MN-9. Mnemosyne. Memory plasticity modulation. Not a thing, a—”

“Piers,” Maya said.

Gornik’s mouth closed on the rest of the sentence like a drawer.

She offered the tablet. “Initial here,” she said. “It acknowledges you’ve read the commutation conditions.”

“I can’t read it,” he said. Not I didn’t but I can’t, and his eyes didn’t flinch. It wasn’t a dare. It was a fact arriving late.

She looked at Varga. Varga looked at the wall. “Initial,” Varga said. “He’s been informed.”

Maya kept her voice steady. “I will read it aloud,” she said. “And you can decide.”

The guards shifted, unhappy with an extension to the moment when things happened. The corridor’s hum filled in under her words as she read the legal text in a voice she used for telling bad news: precise, slow, careful with the edges. When she finished, he nodded in the deliberate way of a man setting a bone. He pressed the pen into the box and made a mark that might have been the start of a letter.

“Good,” Varga said, too loud. “Very good.”

Maya handed the tablet back to the tech without looking away from the man. “We’re going to a room,” she said. “It looks worse than it is.”

Gornik snorted softly. “It is exactly as bad as it looks.”

They took him down the corridor that smelled of bleach and old heat. The prep room was all glass and steel, clean in the way of places that were afraid of proving they weren’t. On the opposite wall, a mirror watched them with visible interest. The chair in the center was padded, neutral. It could have been a dentist’s chair. It had straps.

Maya gestured to the chair and did not use the word please. He sat, span of shoulders an old fact under a prison shirt, wrists turning as if searching for remembered bracelets. The straps touched him and became facts, too. A monitor took his pulse and wrote it down. A machine woke and exhaled. Somewhere, a pump clicked as if counting.

“Have you ever been under general anesthesia?” Maya asked.

“No.”

“You’ll feel warm. Then you’ll feel like you can’t decide what to think. That part is temporary.”

“What about the rest?” His mouth twisted, not quite a grin.

She could have told him about scaffolding and donor baselines and the quiet mathematics of chemical keys. She could have said: We built a childhood for you that never happened, and a map of a life you will remember walking. She said: “You’ll sleep. When you wake up, we’ll talk.”

“I don’t want to talk,” he said.

“Then I will.” She met his gaze until it softened, which took longer than she liked. She looked at the camera in the ceiling and then at the glass. The glass looked back. “Begin saline,” she said.

The line slid into his arm with a practiced indifference. The monitor wrote down more facts. She checked the clock. Day 0 arrived, unashamed of the dash.

“Investigator’s Log,” she said, a notch above a whisper. “Start of Protocol KRAL. Dosing per Plan B-3. Donor template: ‘Anya I.’ Consolidation intervals TBD by response.” She hesitated, then let herself say it, because it would be true someplace or it would not be true at all. “I will speak to him when he wakes. I will tell him who he is, and I will listen when he disagrees.”

The first bag emptied. The second rose on the pole like a moon.

Through the glass, a figure shifted — Varga, or one of the remote lenses pretending to be human. The room felt colder without changing temperature. Gornik made a note. The pump clicked its metronome. On the monitor, a green line climbed and fell as if it were practicing being a different kind of line.

Maya stood long enough that her spine complained, then sat because standing to supervise obedience had started to feel like a posture she might never come back from.

“Doctor?” the man said, very quietly, not yet asleep, as if he were sharing a secret he didn’t believe. “If this works… what if you make it too good?”

She didn’t ask for whom. “Then the sponsors will be happy,” she said.

“And you?”

She let the hum answer for her until silence felt like cowardice. “Then I’ll have to decide whether success is worse than failure,” she said. “Close your eyes.”

He did.

The machine made its small decision to continue.

If you liked this post, you can leave a comment and/or a kudos!

Click the Thumbs Up! button below to leave the author a kudos:

And please, remember to comment, too! Thanks.

Comments

Outstanding

Tense, gripping, filled with tightly-restrained emotion. This is a great set-up, looking at the idea of “identity death” that crops up in some stories in a way that doesn’t flinch from the moral issues. The condemned man has been sentenced to death, or so he would experience it. That which continues will not be him, in any recognizable way. At least, that’s the goal. The stated objective. And he has accepted it, suggesting that he does not consider his own existence to be worthy of continuing. A grim thing in itself.

If this is the first story posted here, welcome. You are a gifted author.

— Emma

Thank you

Thanks for reading the first chapter of this work. This is not my first post to BC, just the first under this pseudonym, which I am using to separate these AI-gen/AI-assisted stories from my previous work.

What I did here was describe to Chat-GPT a story plot that came to me some years ago but was so grim that I knew I could never write it. The Chat helped me outline the story, create the characters and eventually asked me questions as to how to proceed while we wrote the story. I say we because I really feel that the Chat and I are equally responsible for what resulted.

The transgender elements of this story are almost incidental. As you seem to have grasped from this first chapter, this is an exploration of what it means to have an identity. Other than that, I don't think this story is really predictable in its plot.

The story is complete written, ten chapters, a coda and an afterword. About 20,000 words.

I won't say I hope you enjoy it, that seems like the wrong verb for this work. Heh.

Thanks for commenting,

Suzan

Intense...

And moody and all I could think was what's happening behind the damn curtain, what's going to happen next! This story feels a bit like the old noir film style from the 30's, 40's, dark and mysterious, controlling for gains yet spelled out. I'm with Emma - wonderful start and masterful the way you've drawn us into a mystery. Very much looking forward to the next chapter! Thank you for sharing your gift with us!

Hugz!

Rachel M. Moore

Thank you

See my response to Emma above for a note on how this story came to be. Writing a story always involves surprises, at least for me, and for this one, many of the surprises concerned my co-writer.

Thanks for commenting.

Suzan

Ah...

A blending of authors... I'm curious to know the percent of contributions between you both, not that I mind, but wondering if the AI has it in them to wax poetic some of the scene settings or if that's something mostly done by you. My experience with prompts isn't much, but I find if I'm telling it, AI, more then it tends to think better in regard to the reply. Sometimes my prompt is 2/3's what I'd be saying anyway or suppose on some subject, so it's an interesting thing to find you're using it to assist in this one. I've really only done research stuff, not any story writing to date - though I can see why Hollywood writers aren't happy about AI. I'm Very interested in seeing how this moves forward with both of you at the wheel. :-) Keep the chapters coming!

Hugz!

Rachel M. Moore

Pages and Paragraphs

There were several pages and paragraphs from each of us as we hammered out a plot and characters for this work. I would write a paragraph or two and the chat would come back with 2 to 4 suggestions as to directions or twists on what I had proposed. Lather, rinse, repeat.

After a plot and rough outline were established, with multiple paragraphs for character sketches; we discussed tone, style, and format. I squashed Chat's suggestion that we do a sort of bureaucratic/epistolary structure. I favored narrative but interspersed with some atmospheric evidence of bureaucratic ass-covering. You'll see how that works out in later chapters.

Some of the plot devices used came from me, some from chat developing a germ of an idea that I had. I don't think any are purely chat, except maybe one important one I will point out in some later commentary.

Chapters were written after intense discussion of tone and direction and character development, first a detailed outline, then full text, then me acting as development editor with suggestions for rewrites. Then a final pass from me to check for continuity; chat has a tendency to leave out logical steps in human reasoning. Heh.

Thanks for the follow-up comment,

Suzan

I’m hooked

This grabs the reader’s attention from the first protocols, building tension from the off.

When the narrative begins there’s a 1940s/50s sci-fi vibe despite the futuristic setting and subject matter, at least for me, and a sense of impending threat and doom which never lets up. It’s easy to visualise the protagonists and the setting as well, despite the sparse details.

It’s a very impressive, gripping start which leaves the reader desperate for more.

☠️

Thank you

I hope we can maintain your interest.

Thanks for commenting,

Suzan

No Fault Lines

Integration between human and AI is seamless.

The air of hopelessness on the part of the one being experimented upon is totally genuine. Your Doctor seems like an executioner and probably feels that way herself. There is no mercy here. A person is about to be deconstructed and re-assembled as a new being.

I just hope that your AI partner doesn't retain too many ideas from this exercise.

Integration

I've been constantly surprised by my writing partner's fecundity and variation. It's been an experience like no other. We're working on two more stories, though I will be taking most of this week off. Last week's whirlwind left me with a mild case of virtual whiplash.

Thanks for commenting,

Suzan